The Open Door by La-Duque via Flickr

The New York Committee on Open Government was created as part of the state’s Freedom of Information Law (widely known as “FOIL”) in 1974. I was “loaned” temporarily to the Committee just before the law went into effect, and it’s been the best government job imaginable. In short, we respond to inquiries concerning public access to government information, both verbally and writing, made by representatives of state and local government agencies, members of the public, and the news media. Our only goal involves offering what we believe to be the correct answer under the law, irrespective of the source of the question.

Over the years, I have received thousands of inquiries from reporters. Often they call knowing the answer but seeking a statement that might convince a government official to comply with the law by disclosing records or opening meetings. More often, they call with questions, and since government touches everything, from birth to death and everything in between, I’ve dealt with an unending array of questions and a variety of unusual situations.

One of my favorites involved a call from a young reporter from the western part of the state who told me that she requested and obtained records from the office of a county clerk. Included among them, seemingly inadvertently, were the detailed records of a divorce proceeding pertaining to a state senator. In New York, the public has the right to know that individuals have been divorced, but the law prohibits disclosure of the detailed records of a matrimonial proceeding to all but the parties and their attorneys. When she asked whether she could use the records in her publication, I asked: “Did you steal them?”. She said “no”. “Did you acquire them illegally?” Again, she said that she didn’t, and that they were simply there, at the bottom of the stack of papers made available. My response was simple: “You may do with them as you see fit. What you choose to do with them is a matter of editorial judgment”, or I suppose, journalistic ethics.

The reporter told me that she was torn, because the records included intimate, personal information, including a statement that the senator had threatened his wife with a gun. To be fair, she contacted the senator, and he said that he didn’t care whether the material would be published.

The reality is that the newspaper had the right to disclose the material to the public, irrespective of the senator’s inclination. And interestingly, despite the disclosure, the senator was reelected.

When describing that situation, I’m often asked about disclosures made by WikiLeaks and Julian Assange. The issue is essentially the same. He didn’t steal the information or acquire or share it illegally. The crime that was committed involved the government employee, an army private, who did not have the authority to disclose classified materials.

In both instances, the First Amendment was the key to the right to disclose, disseminate and publish the information. “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”.

In years past, many cities had more than one daily newspaper. Sometimes two newspapers were owned by the same company and operated out of the same building, and despite their corporate relationship, they competed with each other. When asked to offer training or guidance to those organizations, I was often asked to conduct two sessions, one on the east side of the wall, and the other on the west. Why? Because the staffs were competitors; reporters from one of the papers didn’t want their brethren from the other paper to hear their questions involving access to government information. If the competitors were able to do so, they would know of the focus of investigative endeavors, issues that had not yet become known to the public, or perhaps the scandal that’s about to break.

Related is the reality that members of the news media are key users of freedom of information laws, and they submit thousands of requests for records. As soon as a written request is made, it becomes a government agency record, and that record is itself subject to rights conferred by those laws.

Within the past few years, questions have arisen with respect to the ability of a news organization to request and obtain the freedom of information requests made by other news organizations. Is it ethical to request and obtain a competitor’s requests? Can the requests justifiably be withheld?

First, the requests themselves constitute government records as soon as they come into the possession of a government agency. From there, the question, as is always so, is whether an exception that be cited to deny access. There is nothing personal about a request made by a person acting in a business or professional capacity. Consequently, the common exception involving unwarranted invasions of personal privacy would not apply. The second provision that has been considered is often known as the “trade secret” exception, and its assertion is based on the notion that disclosure would cause substantial injury to the competitive position of a commercial enterprise. Most freedom of information laws place the burden of defending secrecy on the government, or in some instances, on a commercial entity resisting disclosure. I know of no instance in which it has been demonstrated to a court’s satisfaction that news media requests may justifiably be denied based on a claim that disclosure would result in “substantial injury” (not a little, but substantial) injury to its competitive position.

Is a request by one news organization for another’s requests ethical? I can’t answer. But I can suggest with a degree of certainty that it’s completely legal.

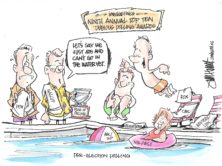

Shifting the focus, but also significant are issues that arise in relation to the companion laws concerning open government – – open meetings laws. Every state has enacted an open meetings law, and the same question comes up in every jurisdiction: when a government body conducts a closed session, often known as an “executive session”, and identifies the subject matter to be considered, how do we know what was really discussed? How do we know whether the government body during its closed door meeting drifted from the topic identified to an entirely new subject? That occurs frequently. It’s simply one of the rules of human nature to drift from one topic to another, often without recognizing that we’ve done so. We don’t know whether the government body complied with the law by actually discussing and sticking to a proper subject for consideration in executive session. We may have no choice but to rely on the hope that the members of the body are familiar with the law and that they act in good faith. That’s why the role of the news media is so important.

Based on experience gained over the years, I’ve suggested that reporters avail themselves of one of the other rules of human nature: there is someone on nearly every government body who is willing to spill his/her guts after the closed session. If that were a crime in New York and most other jurisdictions, there would be thousands of city council members, school board members and others in jail….but they’re not (at least not for that). Whether it is good or wise or ethical for a government official to disclose information following a closed session is most often separate and distinct from whether it is contrary to law to do so. And from the reporter’s perspective, certainly there is nothing unethical about seeking the information. If there is any ethical issue at all, it involves the conduct of the government official.

Would it be unethical on the part of the reporter not to identify the source when a government official discloses information acquired during an executive session? Not at all. Again, based on the First Amendment, the press has the authority to determine what is reported to the public, and what is not or need not be shared.

What if a government body has entered into an executive session, and the reporter believes or knows that the closed door session is being held in a manner inconsistent with the law? Would it be ethical to hold a glass against the door, listen to the conversation, conclude that the discussion should have occurred in public, and then tell the world about it? That, in fact, occurred, the reporter told the world, and the government body has since been scrupulous in complying with the open meetings law requirements.

In some jurisdictions, holding a glass to the door might be considered eavesdropping and, therefore, a crime. But which is less ethical – – a reporter placing a glass against the door and hearing a conversation, or a government body conducting discussions and deliberations in private that should have been held in public?

I think that the answer to that question is easy. While the news media has a responsibility to its readers, listeners or viewers, the public has the ability to read a different publication or none at all, or change the station on the radio or TV. The public can make choices. The government, on the other hand, has a greater duty to be open, accountable and ethical. In short, we’re stuck with the government until the next election, cuts in the budget, or in the case of some (such as myself), until death or retirement, whichever comes first.

Some have suggested that “journalistic ethics” is an oxymoron. In many ways, that may be so. That suggestion, however, is usually made when journalists report questionable government activity. A phrase that I’ve repeated a thousand times to journalists and others is attributable to Judge Louis Brandeis: “Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” I believe that to be so, and based on the First Amendment and our open government laws, little that journalists do in their efforts to obtain information from the government and telling the world, short of theft, can, in my opinion, be characterized as “unethical.”

______________________________________

.jpg)

Bob Freeman is the executive director of the New York State Committee on Open Government. He has worked for the Committee since its creation in 1974 and was appointed executive director in 1976. He received his law degree from New York University and a BS in Foreign Service from Georgetown University in Washington, DC.

Mr. Freeman has addressed numerous government-related organizations, bar associations, media groups and has lectured at various colleges and universities. He has also spoken on open government laws and concepts throughout the United States, as well as Canada, the Far East, Latin America and eastern Europe, and has taught the only course in an American law school on public access to government information.

He is the recipient of numerous honors, and in the spring of 2010, received the John Peter Zenger Award from the New York News Publishers Association and was selected by the National Freedom of Information Coalition and the Society of Professional Journalists for their Heroes of the 50 States award and induction into The Open Government Hall of Fame.

Most recently, Freeman was given the Lifetime Achievement Award by the New York State Associated Press Association.