Over the last few years, a “Fauxtography” epidemic has been steadily infecting the reporting done by many different news outlets. From the infamous Reuters Passion of the Dolls scandal in 2006, to the numerous fake Monster Pig photographs initially verified by the Associated Press and Fox News, it is clear we are living in an age when seeing is no longer believing. iMediaEthics’ Nathaniel Janis recently had the chance to sit down with Jim Hoerricks–forensic analyst with the Los Angeles Police Department–to discuss ways to identify such photos when they appear, and other issues relating to digital photograph manipulation.

iMediaEthics: Could you describe what you do as a forensic video analyst for the Los Angeles Police Department’s Scientific Investigation Division?

Jim Hoerricks: It’s a pretty straightforward job description. As far as digital, analog, or any multimedia-type evidence goes, whether it be crime scene, CCTV footage, or audio recordings or surveillance that’s done by officers – it comes through our office, and then it gets processed either for comparison or straight out for the media.

- Jim Hoerricks

If they’re looking for just a cell image to put on a flyer, or as part of an Amber Alert, there are a lot of different things to do with the video. After that’s taken care of, the audio side needs to be clarified and cleaned up so you can hear what’s going on. Finally, we may have to complete certain tasks like identifying a face, license plate, distributing the video to the media or a patrol unit; that sort of thing.

iME: What would be one of your most common or typical objectives when you’re looking at a video from a crime scene? What do you normally have to determine?

JH: We mainly focus on identification of an individual or an object; you know, did subject A do this? Is this subject A? Does the person in the video or the image match the person that we think did it? Or can we get a license plate? Or if we can’t see the person’s face, is there anything identifiable about the person or the object that we can get out there to the public, whether through the media or crime bulletins internal?

iME: You’ve been significantly involved in many projects – including a book and a website – devoted to Adobe’s Photoshop program. How did you begin working with the program, and what makes Photoshop and other digital photo applications so valuable and widely used as forensic tools?

JH: Well, as you indicated, [Photoshop] is just one of them, really. We have so many of them at our disposal, and when it comes to working with the images themselves certainly we don’t just use Photoshop. I happen to be somewhat of an expert on that particular tool, but we also use GIMP, Photo Dot Net – there are several programs that do different things – even Lightroom, Bridge, and Premiere.So for the most part, when you come into a unit like mine, and you’re presented with a set of tools – kind of the industry standard package – Photoshop Premiere is in there because it’s very clear on the best way to perform certain tasks. This is especially important in law enforcement, when you have to take detectives off the street and put them in front of computers. They’ll be asking themselves, “What do I do? What should I do first? What should I do second?” Those types of things. That’s why Photoshop is kind of what everybody is using, and so it’s what everybody needs to know. But it certainly doesn’t stop there.

iME: Recently there was an article in Scientific American that listed tips for spotting “fake photographs,” i.e., images that have been digitally manipulated. What are some of the differences in procedure, and maybe some of the unique challenges in assessing video data, as opposed to photographic samples?

JH: Dr. Hany Farid at Dartmouth recently conducted a study funded by the FBI on examining the data underlying MPEG-2 and MPEG-4 files – looking for errors in the data rate, errors in the groups of pixels, and so forth. This didn’t really involve looking at the samples visually, but instead examining the underlying data.A lot of that kind of stuff can be done with images, as far as looking to the header and seeing from a data standpoint whether something doesn’t look the way it should, as well as just observing various compositional aspects: Are the light and shadow falling in the same place on the same things? Do the light angles all match up? If there’s an allegation that something was “put in” to the video or into the image, does the data support that? There are a number of tools that can be used to do determine things like these.

iME: You’ve also been accredited as a court qualified expert witness in forensic video analysis. Recently, it has become much more difficult to determine a photo’s credibility, in large part due to advances in digital technology. Because of this, how much value do you find photos are given in legal proceedings,especially in criminal cases?

JH: It’s almost always argued on a case-by-case basis. If no one brings it up in trial then it doesn’t get brought up. If somebody challenges the credibility of a particular piece of evidence, then it gets brought up, and then there’s a hearing about that particular piece of evidence, whether it’s analog or digital, whether it’s audio or video or a still image – it’s always case-by-case.There’s no certain form of media that’s universally excluded. It doesn’t work that way, and so you can get a situation where a particular defense attorney or a particular prosecuting attorney has some knowledge that maybe some other folks don’t. So they take a particular angle in arguing their case based on that knowledge, but to make a blanket statement that analog is better than digital, or digital is better than analog, or you can spoof analog better than you can spoof digital, or one way or the other, you really – it’s all case by case. It really is.

iME: Dr. Hany Farid of Dartmouth University writes on his website, “The technology that allows for digital media to be manipulated and distorted is developing at break-neck speeds.” What are some ways that people can determine whether the photo or video they’re looking at is genuine?

JH: Well, there’s the real world, and then there’s Hollywood. The real world doesn’t have the technological horsepower or know-how to be able to put together a spoof that could pass muster, and so most of the stuff that we see is in a proprietary digital format, or it comes out of a Handycam that somebody hands us, or it comes off of a [CompactFlash] card out of somebody’s camera.In order for the average person to set up something that you’re proposing, they’d have to create a mask to get rid of all of the green or blue fringe, which to pull off requires an incredible blending of pixels. And then you have to consider the rendering horsepower necessary to render that across thirty-frames-a-second multiplied by however long the video is. I mean, you’re talking about a lot of horsepower.I used to be a part-time instructor at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, and one of the projects that the students had to do was to pull off a photo-realistic collage. And so now they’ve got me with my training and abilities critiquing them, and I’m looking, again, back at shadow and light where things are casting across, looking proportionality, looking at edge detail. These are all things that are very, very hard to get right, and the Art Center students are the best and the brightest. This is a place that puts 60 percent of the designers in the industry into jobs, and so these are incredibly skilled people, and even they can’t get edge detail right; even they can’t get feathering exactly right.So, if you put it out in front of you 15 to 20 inches, you won’t notice, but if you get in there, stuff starts jumping right at you. This might have to do with shadow and light, color fringing, color bleed, those types of things. Again, there are people that can do it, but the average person can’t afford that level of service. And so, when you’re thinking about the average crime – you know, thinking about the average criminal getting put into a scene like that, the tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of gear and time and bodies to put that off – for a purse snatch or a liquor store robbery, it just doesn’t make sense, you know? [Laughs] I guess the point I’m trying to make is that type of work is really, really hard to pull off.

iME: So when a video or photo comes to you, it’s not exactly your job to assess or interpret its credibility.

JH: Right, and I think that’s kind of the main misconception. Even though we work for the city and for the police department, and they pay our check every two weeks, we actually work for the judge and the jury. A detective may come in and say I think this is person A, and here’s a picture of person A, and then we do what we do. If the data doesn’t support that, that’s our conclusion.So, sometimes detectives like it, sometimes attorneys do too, but sometimes they don’t. They don’t always get what they want, but they get the truth, so they get what the data supports, and if there isn’t enough data to form a conclusion, then that’s the conclusion in itself. I mean, regardless of what side of the political fence you’re on, just imagine in your mind the average government worker – usually it’s the Department of Motor Vehicles or postal service or something like that. Do you think they’d be capable of doing it?

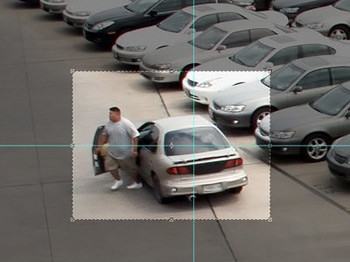

Before and After: Using Photoshop to remove blur and clarify images.

iME: Most of the kinds of allegations we see are directed towards members of the higher echelons of video production, specifically corporate media and network news outlets, so I’m assuming that they’re in a different league from your average worker.

JH: Oh, yeah. It’s different – a different bottom line, too. Certainly our Sheriff’s Office out here and several other places around the country have the expertise to be able to detect these types of things, though not every agency does. But there’s enough information sharing between all the different agencies – I’ve worked cases all over California – I’m loaned to different departments where they don’t have the expertise to be able to pull it off.I did a homicide case in Placer County, where they had already shopped [a video] around to six other agencies looking for help before they came to me, and I was able to get them what they wanted. And so, when it comes to things like that, you know, if you’re trying to prove something, there’s plenty of help available.For a law enforcement agent, if somebody is alleging that “this is a setup,” or “this is a conspiracy,” and it goes to a small agency where they don’t have adequate capabilities, they could certainly reach out to us, and reach out to New York – reach out to the FBI, even. That’s all help that’s available to them.And this is all part of what Dr. Farid’s work was about. If the allegation is that a Sony employee, or a CBS employee using CBS or Sony’s gear, went in and did all this shady stuff, we can look at the underlying data, and say, “This doesn’t match, this doesn’t work.” Again, if you read Dr. Farid’s work, you’re looking for a certain sequence of events that happens within that data – within the grouping of pixels – and how that’s depicted between the Key frames and the I-Frames, and so forth. If you’re looking for these patterns, and then all of a sudden there’s a break in that pattern, you know something’s up. You know something’s being inserted.So, it might not be visually apparent, but you can see it in the underlying data, and then you can start working from that point in the visual sample. It was pretty impressive work, very important work, and most of us are extremely excited the FBI paid for that research.

The cover of Forensic Photoshop