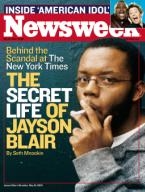

Jayson Blair, featured in this 2004 Newsweek cover, spoke at a journalism ethics conference this November, spurring questions about his fitness to lecture. (Source: [PRNewsFoto][KO]NEW YORK, NY USA)

Last week Jayson Blair, the New York Times reporter now famous for dramatic acts of plagiarism and falsification, spoke at a journalism conference at Washington and Lee University in Virginia. Numerous commentators, including imediaethics, pointed out the incongruity of inviting a person with a history of lying and bad ethical behavior to speak on ethics.

Now, arguing a counterpoint, Justin Pope writes in a November 6 Associated Press article that there actually is some merit in featuring Blair as a speaker; his experience can teach young journalists about failure. However, in making this argument, Pope misses an important point: Blair didn’t really fail as a journalist, he lied, repeatedly, and broke the law–destroying his own career through unethical and illegal actions. Moreover, regardless of whether he is serving as an example of failure (which he is not) or of bad behavior, Blair has proven himself an extremely unreliable source, and thus a poor choice to lecture even on his own experience.

Blair resigned from the New York Times on May 2, 2003 after coming under fire for the similarities between a story he had written for the New York Times and one by a reporter at another newspaper. A committee later determined that approximately half the stories Blair had written for the New York Times since 2002 had problems ranging from plagiarism to outright fabrication.

Pope argues in his story that young people coming into the professional world want and need to hear about failure. “Timothy Noah lamented how many new college graduates were getting commencement advice from the accomplished but boring. Success is admirable but uninstructive, while failure is far more informative — and interesting,” Pope writes.

He is right. Students do have much to learn both about and from failure. Only by understanding how others have failed can we avoid the same pitfalls. But in what sense is Jayson Blair’s experience and example of “failure”?

“For some people, like Blair, failure is spectacular and public,” Pope writes. “For others, it’s just falling short of expectations–in their careers or personal lives.” But this is a false pairing. Blair’s actions, while spectacular, weren’t “failing.” They were intentionally dishonest and illegal. If what Blair did was “failing,” Then we would have to start calling plagiarism “failing to not-plagiarize,” and fabrication “failing to not-make things up.” This seems to be exactly the opposite of what we should be teaching journalism students.

On NPR’s Morning Edition, David Folkenflik reports,

[Kelly McBride] teaches media ethics at the Poynter Institute. McBride says Blair is a case study in epic dishonesty, not good intentions gone awry.

“None of the stories that he was trying to accomplish when he committed his crimes of journalism were the type of stories that change the way we understand who we are, or expose any sort of great wrongdoing.”

If anything, the lessons to be learned from Blair’s experience are those of responsibility for one’s actions. His experience doesn’t warn against failure. It warns against active, unethical behavior.

Yet even this aspect of his experience doesn’t seem enough to make him a good choice to lecture at an ethics conference. As we wrote before, though Blair may be a good example of what-not-to-do, there is little reason to believe that he would be able to talk about his experience truthfully or informatively. It just doesn’t make sense to invite someone who has proven himself largely unable to tell the truth to speak to students.

Pope even brings up this very issue in his article,

Kronman, who has also taught ethics at Yale’s law school, thinks there’s a benefit to talking about failure from an academic and personal distance. He’s skeptical the in-person presence of those who’ve come up short adds much.

When you bring someone back who’s screwed up, it’s very, very difficult to prevent the event from becoming an uninstructive ‘mea culpa’ and a quest for some kind of redemptive validation,” he said. That’s natural, but complicates “an honest and useful assessment of what went wrong.”

Yet Pope still argues here that Blair is a good choice for a speaker.

“There is always going to be pressure to cut corners,” said Edward Wasserman, the journalism professor at W&L who invited Blair. “I suspect what we’re going to find is that he got where he was through half-steps, small steps, rather than a huge leap into completely impermissible behavior.”

Such is the value of hearing from Blair, who perhaps can help students understand better the pressures they will feel trying to break into the highly competitive news business.

Again, this misses the point. Such is the value of hearing about Blair. It is arguable whether there is value in hearing from Blair, because Blair has proven himself to be a prodigious liar. Plus, he is likely, as Kronman argues above, to use his lecture as “a quest for some kind of redemptive validation.”

So, whether Blair’s experience is one of failure or not, at the very least the choice to feature him speaking about it still raises questions. Pope makes two important points in his post 1) That students benefit from hearing about failure, and 2) That Jayson Blair’s behavior might be a good warning to students not to make the same mistakes. But neither of those two points support choosing Blair as a lecturer, since he is 1) not exactly a failure, and 2) unlikely to tell the truth even about his own history.

David Folkenflik who interviewed Blair on Morning Edition writes that when asked if students could trust what he said in his lecture, Blair “gave a half laugh and said they should listen, ask questions and form their own opinions. ‘It’s up to them,’ he said.”