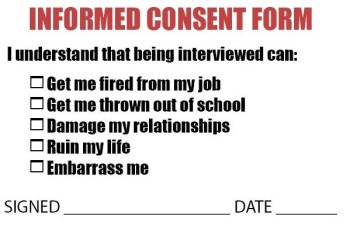

Fictional consent form for sources. (Credit: Illustration by iMediaEthics)

Should journalists do more to inform sources of potential fallout from being interviewed? What are the real-world consequences for media subjects?

The Canadian Association of Journalists‘ Ethics Advisory Committee addressed these key questions in a new report about how journalists should handle interviews and informed consent. The discussion was chaired by University of Western Ontario journalism professor Meredith Levine.

Levine explained her interest with informed consent and recalled an incident where as a reporter she interviewed a “woman in her fifties suing her elderly parents for failing to protect her from child rape several decades earlier,” in a separate first-person article sent with the report.

After the first news reports on the lawsuit, the woman suddenly refused to speak with her again. Levine learned of the negative effects on her source that resulted from her story. “Her intimate relationships were frayed,” Levine wrote in her article, “and a toll was exacted on her mental health.” That incident along with others from her previous work as a journalist for the CBC and her personal past, both working with the medical community and as a patient, raised questions for Levine about consent.

“Now, I look back and ask myself the following question: did I have an obligation to inform this woman that publicizing intimate information could have an impact on her life and her relationships? Back then, this question never occurred to me or to anyone else in my newsroom,” she wrote.

Four-person group discussed consent for the report

Levine, who chaired the panel discussion for CAJ, wrote her 2010 thesis for Carleton University’s masters of journalism studies program on the subject titled “Consent and Consequences: Journalists’ Duty to Inform Subjects of Potential Harms.”

The fourteen-page ethics committee report, published Tuesday, features a back-and-forth discussion under the umbrella of five questions among its four panel members about whether journalists should warn sources of the potential troubles resulting from being interviewed. It took more than a year to produce the report, Levine told iMediaEthics.

The report is written by panel members Levine, a Western University in Ontario graduate journalism professor; Toronto Star public editor Kathy English; CBC ombudsman Esther Enkin; and CBC producer and the Senior Producer for CBC’s fifth estate investigative news program Julian Sher. Issues that sources may face after an interview run the gamut from “mild ‘source remorse'” to tangible problems like being fired, the report explained.

English, Enkin and Sher coordinated their responses as one argument that countered or agreed with points raised by Levine. Among the five questions related to consent and interviewing, the discussion included the risk that sources face and where the line is between the public interest and minimizing harm.

iMediaEthics asked Levine what prompted the discussion. Levine told iMediaEthics by e-mail that she had suggested the topic of consent in 2012 and the committee took up the idea. There was no specific incident or scandal of source violation that prompted the report. Ivor Shapiro, the CAJ Ethics Advisory Committee chairman, confirmed this with iMediaEthics.

According to Levine, it did take a little time to get the committee interested in the topic of informed consent, but over the year, the committee — and specifically the panel of English, Enkin and Sher — became more open to discussing the topic. “What you read in the final report is a considerable shift from where they began,” Levine wrote.

Sher says, “my job was always to try to get consent”

Sher explained that committee members volunteer to work on these types of position papers and discussion topics. Informed consent wasn’t something he’d thought of from this angle, he said, because as a working journalist, “my job was always to try to get consent” and not think about the larger picture of what does that consent mean.

“I was intrigued by the whole notion of how far should we go to make sure” sources understand consent, Sher said by phone.

At first, he said he questioned “why is this even an issue, because when someone gives us consent, that’s where it stops.” He described his initial reaction as, “We’re not social workers, we’re journalists.”

But while he says he “didn’t fundamentally change that,” he did say that he started to see things from another perspective: Journalists are “also human beings, so we also have to care about the people we are interviewing,” he said. “It is a balancing act.”

“Our fundamental duty is to the public, not to the people we interview, to the people we target in our investigations,” he added. “If some people get angry, or hurt, or upset at what we write, that is secondary to serving the public.”

But, Sher said soon in the discussions he started to realize “the members of the public we interview are also members of the public” journalists serve.

“You can’t have great respect for your public who is reading you and not have respect for the public who agrees to talk to you,” he said.

Sher noted he is against “policing” or licensing journalists, regardless of any discussions of a need for a higher standard for consent.

How much ID is enough?

You can see from reading the report how the panel members, including Sher, considered the issues and were open to changing positions. This was especially true in a discussion on the “current media law” and its protection of sources. Unlike in the US., Canadian journalists are legally bound to identify themselves as journalists and to name their news outlet, the report stated.

English, Enkin and Sher wrote in the report that the law was sufficient and journalists don’t have to give any additional information, but after a back-and-forth discussion with Levine, the three did emphasize the importance of making sure that sources know what they say will or may be published.

While three of the four panelists — English, Enkin and Sher — all argued that journalists don’t have to go “beyond identifying ourselves as journalists,” Levine said “the average citizen” may need more to truly be an informed source.

Levine may be called out by journalists for going too far when she suggested likening a journalistic treatment of a source to health care provider’s responsibilities.

“Making a decision about giving an interview without being provided information about potential consequences cannot be characterized as anything other than acting blindly,” she wrote, noting that in Canadian health care, if patients aren’t informed of “potential consequences,” they aren’t considered to have given “informed consent.”

Levine’s comparison to health care comes from not only her previous work with a medical university but also her personal experience in the health care system. In a first-person article about her interest in consent, she wrote about her hospitalization at a teaching hospital at age 13.

“I was subjected to repeated tests, exams and procedures, some of them potentially harmful, even dangerous,” she wrote. She described an incident when she underwent tests that she didn’t need because the medical students needed the experience.

Improved disclosures to sources must be discussed, the Panel concludes

English, Enkin and Sher all suggested that journalism schools address consent issues.

“At a minimum, news organizations should have a working understanding or definition of who ‘vulnerable’ subjects are, and whether there are steps that should be considered before publicly identifying him or her and all of the information revealed to the journalist,” they wrote.

They added that both news outlets should create “guidelines and training” and journalism schools study the reporter-source relationship.

Levine called ensuring informed consent an ethical necessity. “Failing to disclose” the “possible consequences” of an interview, she wrote, is a failure of

- truth

- accuracy

- fairness

- public good

- logical and ethical consistency

- and more

Enkin also wrote about this issue in an article published on J-Source this week, noting the discussion among the four lasted “the better part of a year.”

Sher and Levine will discuss this topic at the CAJ’s annual conference May 9-10 in Vancouver.

The Toronto Star’s public editor Kathy English said she is working on a public editor column about the topic. We’ll update with a link when it’s posted.

Read the report.

See Enkin’s article on the report.

Read Levine’s first-person article on her interest in consent.

UPDATE: 5/1/2014 9:46 PM EST: Kathy English has publishd a column on the paper and committee’s discussions.