One of Robert Capa's iconic D-Day photos. (Credit: Magnum Photos/Robert Capa)

Editor’s Note: Photography critic A. D. Coleman submitted the commentary piece below about his experience researching Robert Capa and his now-iconic World War II D-Day news photographs. He also discusses the problems he found with a report from U.S.-based National Press Photographers Association’s publication, News Photographer, on the Capa controversy provoked by the investigation conducted by Coleman’s team.

We are publishing Coleman’s commentary because we find it raises important issues in photojournalism ethics and journalism ethics. In the course of fact checking, we heard back from many of the main parties involved and have added their responses in bracketed italics throughout the text below.

Given the clear ties that NPPA, News Photographer, and its then-editor Donald Winslow have to the matter, iMediaEthics believes a disclosure should have been added to flag any potential or actual conflicts of interests for readers. They also failed to respond to Coleman’s ethics complaints or allow him any venue to voice his complaints as News Photographer has no comments section and didn’t publish his remarks.

Coleman’s piece is especially timely as in December 2016, marking John Morris’s 100th birthday, the former photo editor for Life Magazine essentially confirmed in a New York Times interview one of the author’s central claims, that only 11 iconic images were taken and the romantic tale of destroyed images didn’t add up. Morris’s comments to the Times confirm significant aspects of the research Coleman and his team undertook. Prior to publication, we again contacted Morris, Winslow and the author of the News Photographer piece in question, Bruce Young, for comment in light of the Morris-New York Times interview. Winslow and Young declined to comment on the record. We waited several weeks for a response from Morris, who we learned is ill, and after publication, Robert Pledge, co-founder and editorial director of Contact Press Images and editor of Morris’s book Somewhere in France, spoke with Morris in the hospital and told iMediaEthics Morris stands by his comments on the CNN ‘Christiane Amanpour’ show. – iMediaEthics

In 2015, News Photographer, the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) magazine, published a feature article by Bruce Young about the legend of photojournalist Robert Capa’s adventures on D-Day and the fate of his photo negatives, including a controversial independent investigation debunking many of Capa’s claims.

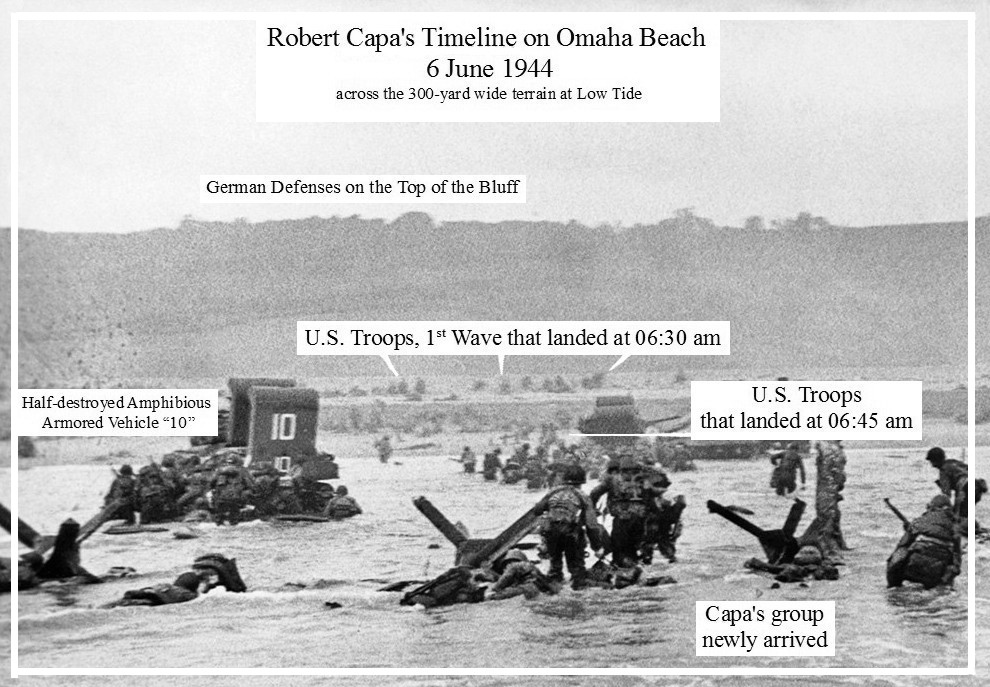

Capa began his famous D-Day tale with his arrival at the “Easy Red” sector of the invasion site code-named “Omaha Beach” in Normandy on the morning of June 6, 1944, claiming that he came in with the first wave of invading U.S. troops. According to his account, he faced horrific enemy fire for 90 minutes while managing to use up his entire supply of black & white 35mm film (somewhere between two and four rolls of film, or 72-144 negatives) — only to have all but eleven of those historic frames accidentally destroyed in LIFE’s London darkroom.

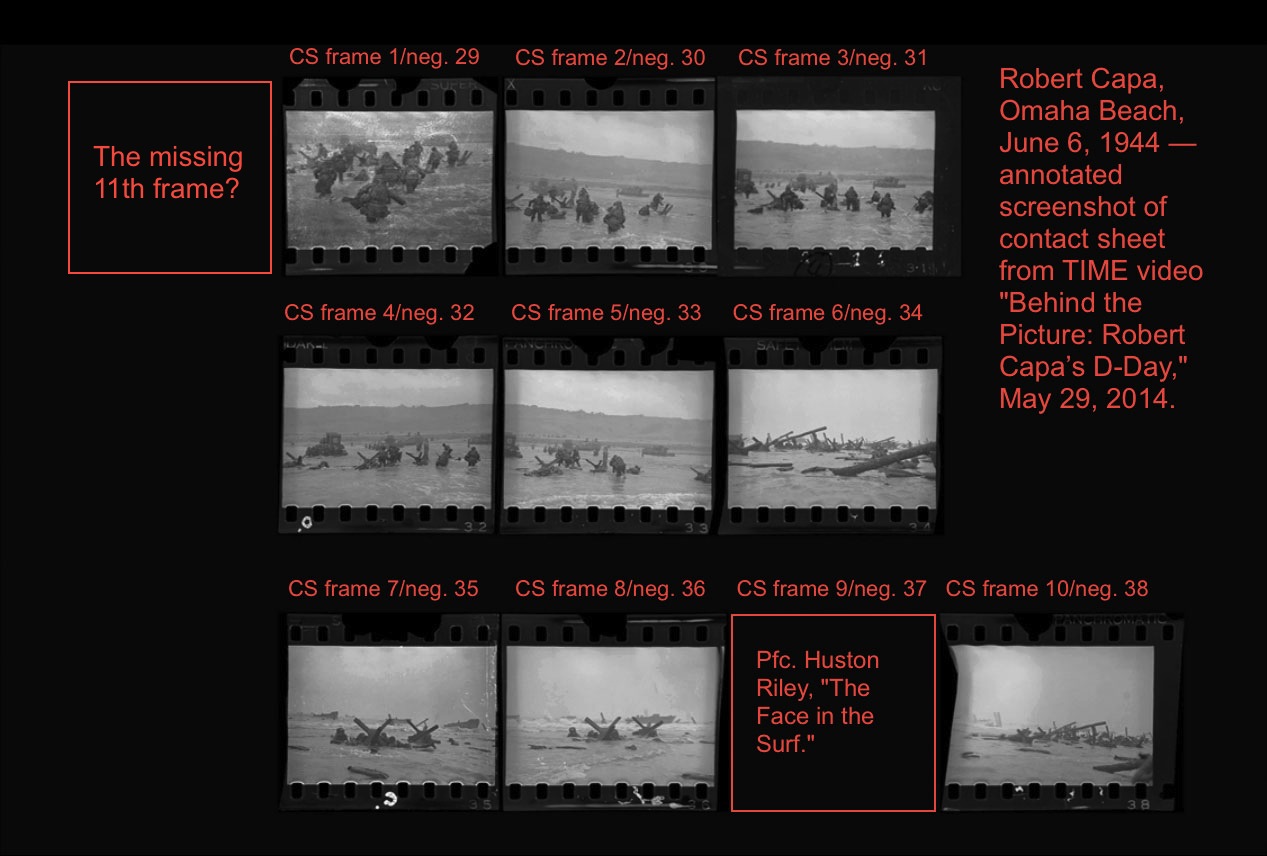

Robert Capa D-Day contact sheet, screenshot from TIME video (May 29, 2014). Annotated by A. D. Coleman.

However, the research I have conducted and supervised, titled “Alternate History: The Robert Capa D-Day Project,” shattered that legend, which has been deeply embedded in cultural history and the lore of the medium of photography, one of the most widespread and enduring myths concerning the field of photojournalism.

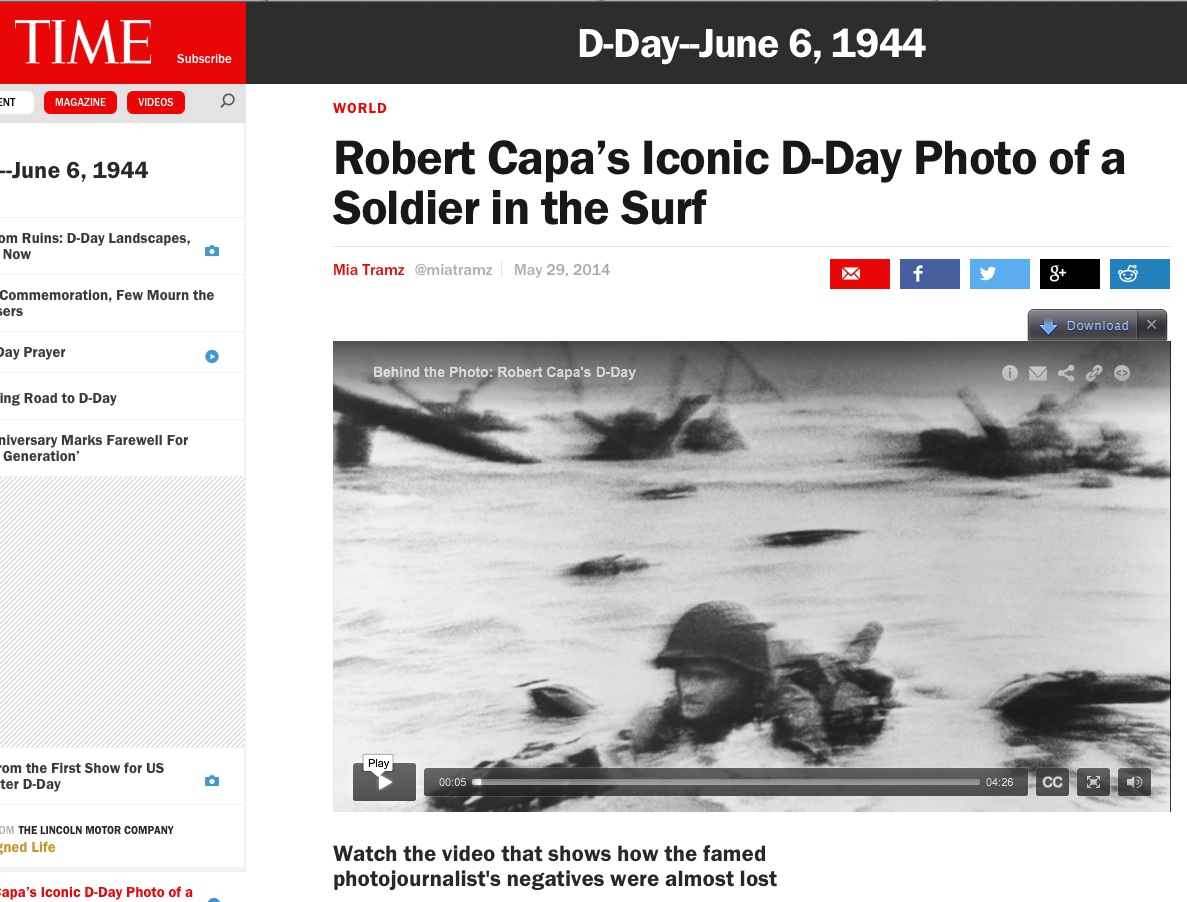

My interest and investigation began in June 2014, when I published a Guest Post by Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist J. Ross Baughman on my blog, Photocritic International (photocritic.com). Baughman, himself an experienced combat photographer, found himself skeptical of the polished legend presented by John Morris in a feature article by Marie Brenner in the June 2014 issue of Vanity Fair and a 70th-anniversary video published on the Time website. (Morris was assistant picture editor in LIFE’s London office, responsible for handling the D-Day pictures turned in by the LIFE photographers assigned to the invasion.) Baughman offered me the opportunity, which I accepted, to publish his challenge to the myth.

In the process of editing, fact-checking, and finding source links for Baughman’s guest post, I realized that it raised more questions than it answered. As a critic and historian, I elected to expand on what Baughman had initiated, simply following my nose.

Along the way, photo historian Rob McElroy and military historian Charles Herrick joined in this effort, with Baughman making several additional contributions. The full result, an extensive deconstruction of the Capa D-Day myth, will wrap up later this winter. A book and touring exhibition based on our findings are in the works.

The author of this report has led research titled, “Alternate History: Robert Capa on D-Day.” (Credit: CapaDDay.com)

As the leader of that investigation, I’m well aware that it raises complex ethical issues concerning the professional behavior of a cluster of famous individuals and powerful institutions, beginning in 1944 and running through the present day. But I did not anticipate that it would evoke from a reputable professional society a startling breach of elementary journalistic ethics when it reported on Capa’s legend and our investigation.

The approximately 7,000-word feature article in NPPA’S News Photographer’s January/February 2015 issue, “The Fog of War: D-Day and Robert Capa,” claimed to put to rest all questions as to what really happened with Capa and his D-Day photos, with the magazine calling Bruce Young’s article “the final word” on the matter in a Facebook post.

In a Facebook post, NPPA called Young’s article the “final word.” (Credit: Facebook/screenshot)

The problems start there. Young’s inquiry was compromised at the outset by the NPPA’s failure to disclose any conflicts of interest and bias and by the article’s uncritical repetition of errors of fact. Finally, after I flagged these troubling issues, NPPA and News Photographer failed to provide me a fair opportunity to respond to its article, as it doesn’t publish comments and didn’t publish my letters to the editor.

Robert Capa D-Day photograph, contact sheet frame 10, negative #38 (left); digitally forged version of a “ruined” Capa negative, screenshot from TIME video (May 29, 2014). Juxtaposition by Rob McElroy.

* * *

With the 75th anniversary of D-Day on the horizon, the time has come to lay this myth to rest.

The research conducted by our team, comprised of J. Ross Baughman, Rob McElroy and Charles Herrick, has debunked every key aspect of Capa’s legend. What did our investigation find? Capa never wrote any meaningful captions for what he had recorded that morning, leaving editors to guess what his photos depicted, and failed later to correct the consequent factoids and misunderstandings, some of which unjustly disparaged the heroic troops he had photographed. The evidence we have uncovered enables the public to reassess both the the legend and the photographs themselves.

Our findings indicate, further, that:

* Capa said he landed in the first wave, but we found Capa arrived when the invasion was well under way, an hour after the first wave of Allied troops hit Omaha Beach;

* Capa claimed that he and the soldiers he accompanied faced blistering enemy fire upon landing; but enemy fire was comparatively light on that section of the beach;

* Capa claimed he made 106 exposures, but our evidence says he shot no more than eleven frames of film while on Omaha Beach (something John Morris, the photo editor, himself has come to publicly accept);

* Capa could have rejoined the unit with which he had come in and continued his coverage but didn’t;

* Capa stayed on Omaha Beach for a half an hour at most;

* And, upon arriving back in England on the morning of June 7, Capa didn’t deliver his film directly to LIFE‘s office, instead turning it over to a courier, whose delayed arrival in London 12 hours later caused a deadline crisis.

Robert Capa D-Day photograph, contact sheet frame 4, negative #32 (detail). Annotated by J. Ross Baughman.

Background: How did the Capa Legend Start?

Capa’s D-Day tale first appeared in print in the September 1944 book Invasion! by Charles Christian Wertenbaker, war correspondent for TIME/LIFE publications, told partly in that author’s words and partly in Capa’s. Capa’s own full version of it plays a central role in his highly fictionalized 1947 memoir, Slightly Out of Focus, which Capa intended as the treatment for a Hollywood movie, and which The New York Times referred to as “his autobiographical novel.”

The cover of Robert Capa’s book, Slightly Out of Focus.

John Morris, the photo editor that day, has since elaborated this story in dozens of publications (including the opening chapter of his 1998 memoir Get the Picture: A Personal History of Photojournalism), as well as in film, video and audio interviews, and countless public lectures.

Through our research on my blog, we have demonstrated that the construction and promulgation of the Capa D-Day myth did not begin and end with Capa’s and Morris’s initiation thereof. Building on the foundation they established, the myth has been propagated and embellished by TIME/LIFE, Magnum Photos, and the International Center for Photography, a cluster of institutions I call ‘the Capa Consortium. Consequently, the tale appears not only throughout the literature on Capa specifically and photojournalism generally, but in popular books, including Stephen E. Ambrose’s D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II and the autobiographies of actress Ingrid Bergman (once Capa’s lover) and Hollywood director Sam Fuller (who met Capa in Italy during WWII). According to Steven Spielberg, it shaped the opening scene of his blockbuster film Saving Private Ryan.

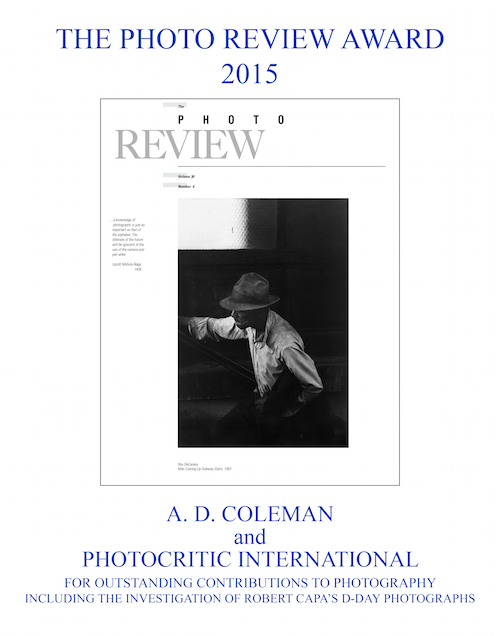

Even before its completion, our Capa D-Day Project has been well-received. Our team’s research earned the 2014 Society of Professional Journalists Sigma Delta Chi (SDX) Award for Research About Journalism, and I found myself honored by The Photo Review Award 2015 “for outstanding contributions to photography, including the investigation of Robert Capa’s D-Day photographs.”

In summer 2015, our critique went viral in France, prompting major feature stories and op-eds in Le Monde, Le Figaro, Libération, Télérama, and an assortment of other print and online periodicals.

* * *

My complaints and conflicts with the NPPA began in June 2014 when I filed a formal complaint against Time, Magnum, ICP, and Morris with NPPA’s Ethics Committee over a Time report that included fake images in a video.

Historian Rob McElroy proved in a report published on my website that Time’s May 29, 2014 video tribute for the 70th anniversary of Capa’s D-Day images, “Behind the Picture: Robert Capa’s D-Day,” included, without disclosure, digitally forged “examples” of Capa’s supposedly “ruined” negatives.

McElroy’s revelation of this deception forced Time to acknowledge the fakery and revise the video overnight. That retraction was covered by PetaPixel and The Poynter Institute, among others. (Note: In October 2016 Time published a revised version of that video as part of its “100 Photographs” project. The re-edited video substitutes a different set of digitally faked negatives for those in the original, presenting them with no indication that they are photo-illustrations. These appear at timestamp 1:49.)

NPPA is a leading organization in the field of photojournalism, and formulated a Code of Ethics for the profession, several of which guidances this Time-sponsored video violated. (Baughman, a former NPPA member, served on the committee that drafted their code). Though I sent this complaint via mail and e-mail to both Donald R. Winslow, then the editor of News Photographer, and Sean D. Elliot, the head of NPPA’s Ethics Committee, I never received any response from NPPA — not even an acknowledgement they received it. (Winslow retired as Executive Editor of this publication in December 2016, becoming managing editor of the the Amarillo Globe-News, the daily newspaper in Amarillo, TX).

[Winslow suggested iMediaEthics ask the ethics chair, Elliot, about this. NPPA ethics chair Elliot confirmed to iMediaEthics the organization received Coleman’s complaint and didn’t respond.]

A screenshot of the Time report.

So when Baughman, the combat photographer whose guest post for my site triggered my interest and investigation into Capa’s story, notified me in late 2014 that he’d had several long exchanges with Bruce Young, assigned by Winslow to write a major feature story on the investigation for News Photographer, and that I should expect to hear from Young, both of us were understandably skeptical.

[“I was skeptical, but at the same time, trying to remain a little bit optimistic,” Baughman told iMediaEthics. ”I had hoped that while he was posturing as ‘Devil’s advocate,’ Young was still weighing both sides carefully. Instead, as I realized after the article appeared, his mind had already been made up, and he was trying to minimize most of what I raised.”]

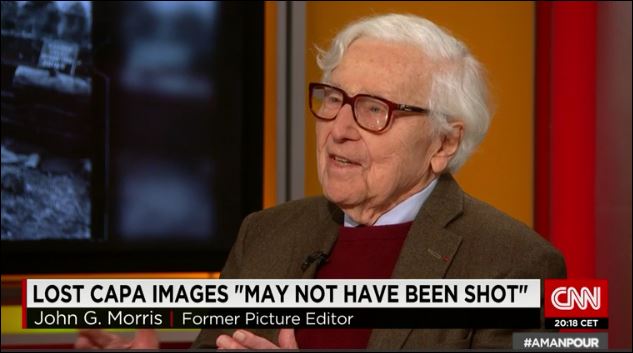

Nevertheless, by then, Morris had begun to recant major portions of his narrative, in a desperate, belated attempt to rewrite what he’d long promoted as historical fact — the existence and accidental destruction of almost four rolls of Capa’s successful Omaha Beach negatives.

In an interview with Christiane Amanpour in November 2014, John G. Morris discussed the famed Capa images and legend. (Credit: CNN)

Morris’s revisionism started in 2014, in various interviews and an e-mail Q & A published on my blog (here, here and here). Morris continued it in two public appearances published online in video format, the first in Luxembourg on September 9, 2014 (starting at timestamp 18:12) and the second in London on November 11 (starting at timestamp 34:26), which also refers to Baughman and my investigation.

Most dramatically, he retracted almost all of the story during a November 11 appearance on Christiane Amanpour’s CNN show, timed for Veterans Day and broadcast worldwide.

“It now seems that maybe there was nothing on the other three rolls to begin with. Experts recently have said you can’t melt the emulsion off films like that and he just never shot them,” Morris said. “So I now believe that it’s quite possible that Bob just bundled all his 35 together and just shipped it off back to London, knowing that on one of those rolls there would be the pictures he actually shot that morning.”

This last confession had evoked from NPPA editor Winslow an astonished Facebook post — “WTF?!?!?!? Former Picture Editor John G. Morris tells Christiane Amanpour that Capa’s ‘lost’ images may never have been shot.” — and an equally astounded tweet.

(Credit: Facebook/screenshot)

[Morris told iMediaEthics we were “wasting time” for contacting him last spring via e-mail for comment about Coleman’s complaints, despite evidence otherwise: “The only thing I have changed in my story is that I became convinced that Dennis Banks was mistaken when he said that three of Capa’s four rolls of 35 mm film that he developed had been ruined by too much heat. I think we shall never know what ruined them – perhaps sea water. I know that I personally inspected them in the Life darkroom that night and threw them away as there was nothing on them — just like Dennis Banks had said. I believe I was the first to see that there were eleven frames (ICP has only ten of them) on the fourth roll. I hope you don’t waste more effort on this; Coleman will love you if you give him more publicity.” Morris also pointed iMediaEthics to his book.]

Hoping for the best but expecting little, Baughman and I cooperated fully with Young (who called and emailed me in January 2015). “I have been assigned by News Photographer magazine to follow up on your recent work regarding the Robert Capa D-Day photos,” he emailed me.

“If the NPPA magazine can help set the record straight, the photo community might learn a more realistic account of what happened, and stop propping up the fantasy,” Baughman emailed Young. “There are enough other examples of Capa’s good work and willingness to walk in the face of danger without relying on false interpretations of his conduct on D-Day.”

We both answered all of Young’s questions in detail, even when that involved matters already discussed at length in the project’s online posts. The results of his investigation would not appear until mid-March 2015, and, sadly, would justify all our concerns about his report on Capa and our research.

The Organization’s Bias

NPPA as a whole has a relationship to former LIFE picture editor John Morris, who promulgated the Capa legend, that one would have to describe as anything but impartial. An NPPA Life Member, Morris in 1971 received the organization’s Joseph A. Sprague Memorial Award, which NPPA describes (arguably) as “the highest honor in the field of photojournalism.” Over the decades he has participated in various NPPA activities; among those, he has served as faculty in NPPA’s annual “Flying Short Course.”

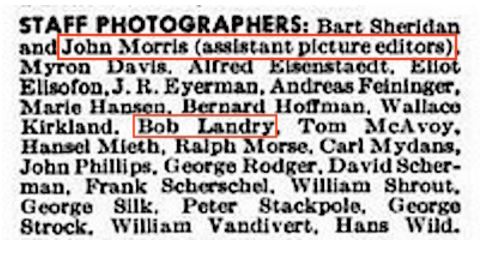

Life magazine’s masthead listing John Morris. (Credit: 1944 masthead)

On its website, NPPA consistently refers to Morris in adulatory terms, such as “legendary photography editor,” “the legend of photojournalism,” “photojournalism’s living legend,” “the undisputed dean of photojournalism, “the eminence gris [sic] of picture editors,” and so on. Articles about Morris, invariably filled with praise, appear there regularly.

NPPA’s connection to Morris therefore runs deep, another possible reason for the organization’s evident reluctance to question the myth in whose creation and dissemination he is implicated. Surely such a predisposition mandated, at the very least, a disclosure notice to preface the article on our project.

The Periodical’s Bias

Notwithstanding its claim to function as “the authority on topics ranging from law and ethics to technology,” the magazine circulates almost exclusively to NPPA’s membership. Its online edition resides in a password-protected section of the site. Non-members cannot access it through any of the online library systems.

[Winslow says, “The magazine comes with an NPPA membership, and is also available for single copy or yearly subscription, and is available for purchase Amazon.com.”]

In addition to running many articles praising Morris, as mentioned above, as well as articles praising Capa, News Photographer has published articles written by Morris on numerous occasions. Furthermore, Morris’s second wife, Margaret “Midge” Morris, who died in 1981, served as the editor of News Photographer from 1974 through 1976. This prior history required disclosure.

[iMediaEthics asked Winslow for comment on Coleman’s concerns regarding conflicts of interest. Winslow simply said, “Not relevant to the article.” He said of his relationship with Capa and Morris, “Capa was never an NPPA member and has been dead for 63 years. I never met the man. John Morris is one of the industry’s iconic and most respected leaders and photojournalism historians.”]

The Editor’s Bias

The article as published neither presented an objective account of our inquiry nor contributed to the search for the truth of the matter. Instead, News Photographer published a whitewash that would find Morris blameless while pretending that NPPA had no stake in the matter.

Some of those conflicts of interest on Winslow’s part have an institutional premise vis-a-vis his position in NPPA, as already discussed. But others involve Winslow’s personal and professional entanglements with Morris, and the unabashedly pro-Morris and pro-Capa stances of both Winslow and Young.

Furthermore, Winslow numbers among those gulled by Morris’s standard account of melting emulsion in LIFE‘s London darkroom, having parroted it uncritically in a June 6, 2006 article for NPPA, “War, And Peace: Robert Capa, 62 Years After D-Day.”

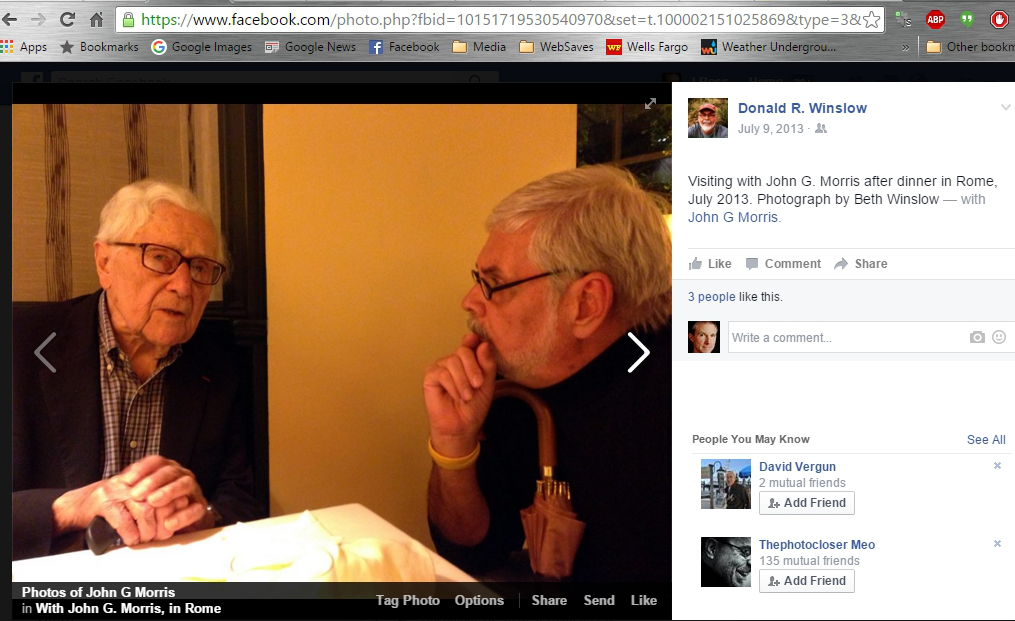

News Photographer included just three photographs as illustrations for Young’s article: The hands of Capa’s younger brother Cornell (founder of the International Center of Photography in New York) holding the surviving Omaha Beach negatives; a half-page group photo that included Morris, Capa, and other LIFE staffers, taken just before D-Day; and a half-page portrait of Morris, savoring a glass of wine “at a summer dinner in Rome with friends in 2013.” The story’s three pull quotes all come from Morris. By leaving faceless those challenging Capa’s and Morris’s credibility, the magazine sends a clear visual and graphic message, rendering us effectively invisible and de-emphasizing our criticism.

After using our research as a reference, the article in both print and online formats omits the title of the Capa D-Day investigation and any URL or link directing the reader to the index page of this project at my blog, requiring readers to search those out online and making that unnecessarily difficult. [When asked about the lack of a URL, Young told iMediaEthics, “That was an editorial decision. However, is it NPPA’s job to promote Coleman’s web site?”]

Well before Young’s article was published, Winslow posted snapshots of himself dining out with Morris in Rome. Winslow’s friendship with and admiration of Morris could easily leave his writer hesitant to confront allegations of long-term deception.

John G. Morris and Donald R. Winslow in Rome (Facebook screenshot)

The Writer’s Bias

Bruce Young, a photojournalist based in Virginia now working for WDBJ, a CBS-affiliated television station in Roanoke, wrote the article for NPPA on Capa. It may be that Winslow selected Young for this assignment because he’d provided News Photographer with an earlier piece on Capa in 2009 commissioned by Winslow, “Death In The Making … For The Last Damned Time,” this one on the controversy over the authenticity of Capa’s Spanish Civil War image “The Falling Soldier, 1936.” In it, Young refers to himself as a “Capa-phile.”

In his email correspondence with Baughman concerning the investigation, Young candidly proclaimed himself a “Capa defender” who was “inclined to give Capa a break.” Yet he does not disclose that in this article. [Winslow told iMediaEthics: “Young is not a Capa defender. Young is a student of Capa’s life, of which I was aware, as well as being a respected independent journalist, photographer, filmmaker, and historian.” When asked the NPPA’s stance on the controversy surrounding Capa and his photos, Winslow told iMediaEthics, “The magazine does not have a ‘stance.’ We report.”]

E-mail screenshot

Young said he wanted to write “a neutral piece accounting for everyone’s stories and claims,” as Young put it to me in an e-mail. But Young had already made his own prior commitment to Capa a matter of public record, and likely had an awareness of Winslow’s allegiance to Morris.

[Young denied any conflict, telling iMediaEthics that Coleman “seems to think that it is unethical to admit an interest or even admiration for a photographer who has been universally praised by the photojournalism world for 80 years. To say that I have an interest in Capa is to explain why I was called to work on this piece, and to call this interest, especially a positive interest, an ethical violation would make virtually any piece written about, say, Martin Luther King, Jr., or Gandhi unethical, wouldn’t it?

“As for calling myself a ‘Capa Defender’ and ‘Capa-phile:’ I thought I was conversing casually with Baughman, not making a formal statement on my approach to journalism to Coleman’s outlet. Frankly, I would have to review the emails, but I suspect that in context the terms make much more sense.”

Young confirmed he knew Morris and Winslow were friends, but said it had no impact on his reporting.

Winslow said NPPA/News Photographer didn’t approve editorial input or guidance for the article. “Bruce Young is the author, the story was copy edited and fact checked via experts who are in a position to know the truth and accuracy of what happened on D-Day.” Young confirmed he had no editorial guidance.]

Young’s article stated correctly that I am not a professional photographer. He also noted that circa 1970, some of the amateur photographers who form the circulation base of Popular Photography, an occasional platform for my work at the time, challenged the legitimacy of my writing about photography, insisting (for no good reason) that only photographers should write about this medium.

A.D. Coleman, author of this piece, and his blog Photocritic International were awarded The Photo Review 2015 award for “outstanding contributions to photography including the investigation of Robert Capa’s D-Day photographs.”

Clearly, though inexplicably, Young viewed that as more relevant to my credibility on these issues than the dozens of articles on aspects of photojournalism that I had published over the previous forty-seven years, or the keynote address to the annual World Press Photo gathering that I gave in Amsterdam in 2000, or my other activities relating to photojournalism, about which I had informed him in our email exchange.

Young had earlier confessed to Baughman that “I’m afraid I was unaware of [Coleman] and his work before this.” The article contains no evidence that Young contacted any other independent critic or historian of photography to determine how the field views my five decades of work or how my peers evaluate this project of mine.

[In response, Young told iMediaEthics: “Have you read my piece? Historians, critics, photojournalists, and people with direct knowledge of the events are cited. I did read his work (more thoroughly than he read my work history). His command of details is impressive, but his understanding of their meaning is vague at best. As I said in another email to Baughman (who BTW admitted an admiration of Capa himself, if I recall correctly), I thought Coleman was a bit out of his depth when talking about documentary production, among other things.”]

Young’s truncated, skewed summation of my credentials comes in a section titled “Who Is A. D. Coleman?” Though Young’s lead-in to this section of his article reads, “[N]ow Coleman has gone down the Capa rabbit hole,” the only complete sentence of mine quoted in the entire approximately 7,000-word article comes in that passage about my Popular Photography readership almost half a century ago, making it irrelevant to the Capa D-Day investigation. The following section — “What Does Coleman Say?” — runs roughly 700 words in length, yet contains only two sentence fragments quoted from my posts: a total of 31 words, 25 of them comprising my year-end mention that a dozen readers had unsubscribed from the blog in 2014, during the period of this investigation. (A crucial point from Young’s perspective, apparently, though for some reason he omits this sentence, which ends that paragraph in the post: “Yet at least as many subscribers signed on during that period, so I’d say we broke even.”)

J. Ross Baughman (Credit: Wikipedia)

Instead, Young prioritized J. Ross Baughman’s contribution to the investigation (though ultimately giving it the same short shrift). It’s understandable that an organization of professional press photographers would highlight the perspective of one of their own: Baughman is a working photojournalist, an experienced combat photographer, and a former NPPA member. Nonetheless, some may find that imbalance odd. Especially since the purpose of the article, as described by Young to me, was “to follow up on your recent work regarding the Robert Capa D-Day photos.”

[Young’s response to iMediaEthics: “Coleman amuses me. This was his very first complaint about the piece: that I gave him insufficient space. He reminds me of a fading starlet counting the number of lines in her script. The piece was not about Coleman or his research, although that was the trigger for it. The piece was to figure out what did indeed happen in 1944. Frankly, in my opinion, I gave Coleman a great deal of credit for his work and treated him very fairly by reviewing his qualifications and opinions, but this was in no way a hagiography of him or even a review of his work. The piece was to be about Capa and D-Day.”

Winslow told iMediaEthics: ”The article was not about Coleman’s research. The article was about what happened on D-Day. Coleman was mentioned merely as a point of entry to our story.”]

Nowhere does Young mention my formal complaint to NPPA’s Ethics Committee in June 2014.

[Ethics chair Sean D. Elliot told iMediaEthics, “I cannot speak to decisions regarding the publication of the article, only the author or the editor would be able to do that.” Young told iMediaEthics: “Which complaint? He does tend to throw them about quite casually and in great numbers. However, again, the piece was about D-Day, not Coleman.”]

Instead, Young offers his own hypothesis of what happened to Capa on D-Day and to his film the next evening, a theory he floated past Baughman (in November-December 2014) and then me (in January 2015), in the guise of what he described as a “devil’s advocate” speculation to which he requested our response.

“It has occurred to me that there is a scenario that more or less accounts for everybody’s beliefs and questions,” he wrote to us. Indeed, his first email to me asks no questions about our research; the bulk of it, following two introductory paragraphs, he prefaces with “Allow me to propose an alternative,” after which he solicits my comments on his own cobbled-together variant of Morris’s most recent effort at self-exoneration.

[Of Young’s prominent placement of his own theory over the research done on Coleman’s site, Baughman told iMediaEthics, “It became a sad example of self-denial and wishful thinking, desperately cobbled together so that the old legend of Capa and Morris on D-Day could be salvaged.”]

In his article, Young takes as his implicit premise the belief that, since everyone’s entitled to his or her opinion, all opinions carry equal weight, and this presumably “neutral piece accounting for everyone’s stories and claims” wouldn’t be complete without including and foregrounding Young’s own.

[In response to Coleman’s criticism of Young presenting his own theory, Young told iMediaEthics: “Again, not about him. God forbid I should disagree with his opinion. Am I not allowed to have my own interpretation of the facts?”]

From our separate vantage points, in our email exchanges with him, both Baughman and I shot full of holes Young’s farfetched attempt to do what scientists call “saving the appearances” — making Morris’s patchwork new account somehow plausible. Yet here it raises its head in print, unfazed by our detailed critiques of its disconnection from fact and logic. Clearly, Young planned all along to elaborate this in the article, pretty much verbatim as he presented it to Baughman and me. (This gets roughly 20 percent of the article.)

For this section Young relies heavily on the response to his questions provided by Morris, which he sent to Young and distributed via email to his own network on January 5, 2015. Titled “The A. D. Coleman Attack,” this section attempts to consolidate and rationalize the various explanations that Morris had started to float in his summer 2014 interview with Mark Edward Harris and continued into the fall. In this “new theory” Morris offers up, among other fanciful notions, the following:

* his newly recovered memory that Capa had sent him a previously unmentioned first shipment of his pre-invasion 35mm films via LIFE staffer David Scherman;

* his freshly minted addendum that (for reasons unspecified) Capa had “somehow” managed to get those films to Scherman while crossing the English Channel separately at night in a 5,000-vessel armada under radio silence in blackout conditions, a remarkable feat also previously unmentioned;

* his speculation that perhaps Capa, the veteran photojournalist, had left his lens cap on, causing so much blank film;

* his conviction that, if he hadn’t neglected to remove his lens cap, Capa must simply have gotten confused and thrown some rolls of unexposed 35mm film in with his lone partial roll of Omaha Beach exposures in the now-second shipment;

* and his assumption that the London darkroom staff, which on the night of June 7 included both the experienced and technically expert current darkroom manager and his equally knowledgeable predecessor, somehow mistook those rolls of unexposed film for films with emulsions melted by heat after development.

Unfortunately, none of that correlates logistically with Capa’s and Scherman’s separate locations in the vast invasion armada, nor their arrival times back in England. None of it fits logically with the narrative and timeline that Morris had reiterated for the preceding seven decades (indeed, much of it contradicts the original version). None of it is consistent with photojournalists’ standard working methods or darkroom practice. And none of it comes substantiated by any hard evidence.

In January 2015 emails to Young, and later in a series of posts at my blog, I highlighted the discrepancies within what Morris calls his “new theory” and between this hasty pastiche and his original account, demolishing it at length, point by point. Yet Young questions none of it and requires of Morris no proof of any of it, instead taking it all at face value, relaying it to News Photographer‘s readers as coherent and credible.

The Capa D-Day investigation the author led and published earned a research award from the Society of Professional Journalists’ Sigma Delta Chi Awards. (Credit: SPJ, screenshot)

* * *

“What happened? Who can say.” This is how Young concludes his piece on our investigation of Capa’s D-Day photos, echoing the closing of his earlier piece on Capa’s iconic Spanish Civil War image. He leaves the last word to John Loengard, ex-LIFE staff photographer turned author and LIFE historian: “Wondering why people haven’t questioned the story of Capa’s D-Day film … Why bother? People like the story. And it’s a better story than that Capa bugged out after snapping only 11 frames, if that’s what happened. … Of course, none of this matters.”

As Thomas E. Patterson wrote in his landmark 2013 book Informing the News, “Faced with contrasting claims, people tend to pick the more agreeable one, even when it’s factually less plausible.” Be that as it may, and Loengard notwithstanding, photojournalism — like journalism, of which it’s a subset — must prioritize the search for truth and commitment to the facts, no matter how messy or disagreeable, over the entertainment value of a seductive narrative. Anything else thoroughly impeaches its credibility as a process of witnessing and/or bearing witness, not to mention making a mockery of any “code of ethics” for the profession.

No Rebuttal Allowed

When News Photographer‘s feature story appeared on March 13, 2015, Winslow refused to grant both me and Baughman access to its online version, on the grounds that it appeared in a members-only section of the NPPA website. By good fortune, an NPPA member of my acquaintance, disturbed by that policy when I announced it at my blog, sent me screenshots of the online version, and alerted me to a backdoor through which one could reach it directly online. This enabled us to read the article.

[Winslow told iMediaEthics: “Clearly they have failed to comprehend the basic premise that the online version of the magazine is behind a firewall for members only. They were told several times to request free copies from the national office.”]

Grudgingly, and only at my insistence, Winslow instructed someone in the organization to send copies of the print edition to Baughman and me; these arrived several weeks later. However, the News Photographer website does not enable commenting on published materials, and the print edition has no “Letters to the Editor” feature. So my responses to the article have gone unpublished and unacknowledged by NPPA. (Both Baughman and I have posted extensive critiques of the feature at my blog.) [In response to this point, Winslow tells iMediaEthics, “Our web site is not capable of online comments. We do publish letters to the editor when they are worthy of publication.”]

After the article appeared, I filed a second formal complaint with the NPPA Ethics Committee. Dated April 2, 2015, this called for “an ethics investigation of Bruce Young; Donald Winslow; the National Press Photographers Association’s journal, News Photographer; and the NPPA.” Like my formal complaint of June 26, 2014, this too has gone without response or acknowledgement of receipt. [NPPA Ethics Committee chair Sean D. Elliot confirmed that he and the committee also received this second complaint, and didn’t respond to it either.]

(Credit: NPPA.org, screenshot)

Conclusion

The presence of the multiple biases listed above suggests that a wise and ethical writer, editor, periodical, and organization should have erred on the side of caution in approaching such a (for them) loaded subject, or else risk becoming a textbook case of conflict of interest. An alternative choice would have been forthrightly revealing the hairball of personal and professional affiliations, recusing themselves from any engagement with our inquiry, and without taking sides, pointing the magazine’s readership toward the research available online and open to comment on my website.

However, albeit ethically complex, the situation didn’t automatically preclude the production by Young and Winslow, and the publication by NPPA in News Photographer, of something substantial that would have contributed in some way to the inquiry. But such an outcome would have required their recognition and acknowledgment of their inherent entanglements and biases. It also would have tested their determination to overcome those obstacles to ethical journalistic practice.

No evidence of such understandings appears in the resulting story. To the contrary, all involved concealed their predispositions and vested interests not only from Baughman and me (we uncovered those conflicts of interest via other means) but, more important, from the readership of News Photographer — primarily composed of NPPA’s more than 6,500 members, led by their professional organization to believe that they are encountering in this article “the final word on Robert Capa’s D-Day negatives and the mystery of 11 images” in an example of objective journalism.

What they read instead are the ruminations of someone who has no substantial track record as a critic or historian of photography, and who prioritized his own hastily formed notions over the conclusions of professionals who had spent months examining the relevant materials and developing a reasoned argument supported by concrete evidence. Presenting this apologia for Morris as “the final word” seems clearly intended not to encourage discussion but — at least for News Photographer‘s readers — to close off further consideration of what our investigation has uncovered.

Tellingly, the journalistic concept of “full disclosure” proves notable by its absence from the NPPA’s Code of Ethics (which only urges its members to “Recognize and work to avoid presenting one’s own biases in the work.”) That may explain — though it doesn’t justify — the fact that nowhere in this lengthy feature do either Young or News Photographer mention the compromising relationships that underlie their extensive personal, professional, and institutional involvement with some of the subjects. That makes this an object lesson in how the failure to recognize and fulfill the journalistic obligation of full disclosure can lead to a major violation of professional ethics — even by an organization that professes itself a standard-bearer and model of ethical behavior in the field.

Regardless of the merits of the case that my colleagues and I have made — which we have always agreed stands open to debate, which we solicit and encourage, and disproof, which we also solicit and still await — we have put our reputations on the line to challenge what I have dubbed “the Capa Consortium,” a cluster of powerful institutions and individuals who have demonstrably propagated the myth of Capa’s D-Day experiences and the subsequent fate of his negatives, and who unarguably profit from that myth in a variety of ways. To date, none of them have refuted effectively any substantive component of what I and my colleagues have presented in “Alternate History: The Robert Capa D-Day Project.“

One wouldn’t know any of that from reading the article that Young wrote, Winslow commissioned and edited, News Photographer published, and NPPA sponsored — a mere facsimile of journalism, deeply contaminated by their fanboy enthusiasms for one of the principals and their undeniably partisan personal and working relationships with the other.

* * *

Postscript, by A. D. Coleman:

The responses to this article that appear above consist entirely of denials, evasions, and ad hominem attacks.

I strongly encourage iMediaEthics readers to review our research via the links provided in this article, and then to read Bruce Young’s article for NPPA’s journal News Photographer — which he and NPPA editor Donald Winslow describe as a “report” that takes no “stance” while offering up Young’s “own interpretation of the facts.” They can then determine whether the blithe and blanket dismissals by Young, Winslow, and Sean Elliot of any and all ethical questions raised by the publication of Young’s article are in any way responsive to the specific charges. They can also decide whether questions concerning conflict of interest and full disclosure are truly, as Winslow asserts, “[n]ot relevant to the article” published by NPPA.

Notably, these respondents have yet to produce any hard evidence disproving any of our research results, or any plausible argument effectively refuting our conclusions. John Morris claims that “The only thing I have changed in my story is that I became convinced that Dennis Banks was mistaken when he said that three of Capa’s four rolls of 35 mm film that he developed had been ruined by too much heat.” This is laughable, as our research and this article make clear. Indeed, of his elaborate original narrative describing his experience and Capa’s, reiterated almost verbatim for 70 years, only Morris’s claim to have seen three and half rolls of blank film remains intact — and now, after ascribing this first to excess heat, then to an overlooked lens cap, and then to confusion on Capa’s part, he’s blaming it on … sea water.

Bruce Young refers to “Capa-philes like me” not in any email to Baughman, as he claims, but in the cited article about Capa that appears (twice) at NPPA’s website. In it he also writes, “As much as I idolize Capa myself …” Readers can decide whether I have distorted the “context” of these encomia. I consider it highly unlikely that anything neutral and objective about Capa could emanate from such a forthrightly biased source. I readily confess my unawareness of Young’s contributions (whatever they may be) to the history of photography, the history of World War II, or both — the two fields germane to this article. Historian or not, he’s surely aware that it is standard practice among researchers in all fields to cite sources and references precisely — title, date and place of publication, URL if online — so as to direct readers to them. (Historians do not generally consider this to constitute “promotion” of said sources.) By his own admission, he and Winslow made “an editorial decision” to exclude such information about our Capa D-Day project and thus flout that basic obligation of scholarship.

Young writes, “Which complaint? [Coleman] does tend to throw them about quite casually and in great numbers.” I filed a grand total of two formal complaints with the NPPA Ethics Committee, only one of which involved Young.

Winslow writes, “The article was not about Coleman’s research. The article was about what happened on D-Day. Coleman was mentioned merely as a point of entry to our story.” I consider this preposterous, but encourage iMediaEthics readers to review Young’s article and make their own determination on that score.

Baughman and I certainly understood the membership-based firewall at the NPPA site. Given the amount of time we spent responding to Young’s queries on behalf of News Photographer, we expected the simple courtesy of ready access to some version of that article (such as a pdf file) as soon as it appeared.

There’s another ethical question for the reader to ponder: What obligation do Winslow and Elliot now have to inform NPPA’s membership of this challenge to their ethics, published at a reputable website devoted to media ethics, one that thoroughly reviewed the article for accuracy? Will Winslow send out tweets and Facebook posts about it forthwith? Will NPPA now add links to this article and to the Robert Capa D-Day Project (capadday.com) from its website, so that the NPPA membership can judge whether its administration has engaged responsibly with published charges of unethical conduct?

In closing, let me express my thanks to Rhonda R. Shearer, founder, publisher, and editor-in-chief of iMediaEthics, for encouraging me to write this article for that platform, and to Managing Editor Sydney Smith for her assiduous fact-checking of my text and helpful editorial suggestions for its fine-tuning.

A. D. Coleman is an internationally known critic of photography and photo-based art, and a widely published commentator on new digital technologies. He has published 8 books and more than 2,000 essays on photography and related subjects.

Formerly a columnist for the Village Voice, the New York Times, and the New York Observer, Coleman has contributed to ARTnews, Art On Paper, Technology Review, Ag (England), European Photography (Germany), La Fotografia (Spain), and Art Today (China), among other periodicals. His work has been translated into 21 languages and published in 31 countries.

Coleman’s blog is Photocritic International. The Capa D-Day Research is Alternate History: Robert Capa on D-Day.

UPDATED: 2/27/2017 7:19 PM EST Updated editor’s note with Pledge’s response.