(Credit: New York Times)

According to a recent Pew Global Attitudes Project article, a Pew poll of Muslims in Egypt last year found that about six in ten believe democracy is “preferable to any other kind of government.”

The article was written in the wake of the widespread demonstrations in Egypt, though the poll itself was conducted nearly a year ago, between April 12 – May 7, 2010.

Clearly, the article was meant to give the American public an insight into the thinking of Egyptians citizens as they face a government crisis. And the information would be appear to be positive: With Muslims constituting about 90% of the population, such widespread supportive attitudes about democracy should signal good news for those interested in a transition of the authoritarian government to one that is more responsive to its citizens.

However, a closer examination of the Pew poll suggests that the good news of an Egyptian public highly receptive to democracy is at best overstated, and at worst may be just plain wrong.

Biased Question on Democracy

The Pew poll question about democracy is incredibly biased, without doubt significantly overstating positive responses.

Here is the question asked of Muslims, followed by the instructions to the interviewers:

“And which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion? Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government; In some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable; For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.”

(INTERVIEWER INSTRUCTION: read statements in language of interview, but always read “democracy” in English. Translate “democracy” into local language only if respondent does not understand English term.)

(Credit: Pew survey)

Note that the question does not pit democracy against any other type of governing structure, such as a monarchy or theocracy. Instead, it focuses solely on democracy, implying a democratic bias on the part of the interviewers.

Imagine measuring the most popular auto maker in the United States by saying: Please choose from the following options – 1) Ford is preferable to any other car company; 2) in some circumstances, a non-Ford produced car can be preferable, or 3) for someone like me, it doesn’t matter what car company I buy from.

The polling organization that asked such a question would be dismissed as a biased partisan for the Ford company. If Pew truly wants to discover the views of Muslims (or any other group) about various forms of government, it needs a more balanced question.

For Muslims in Egypt, one such question might be: “Which type of government system would you prefer – one where the laws are made by the people and their elected representatives, or one where the laws are made by religious leaders based on their interpretations of the Koran?”

The Elusive Meaning of “Democracy”

Note also that in the Pew question, the word “democracy” is not translated into Arabic or any other language, but is spoken only in English. We don’t know how respondents interpret this word. Pew didn’t ask respondents to characterize their own government, and for all we know, they may think their own government is a democracy. Or when they think of “democracy” (the English word), many respondents may think of the United States, where most people are financially well-off. Thus, when such respondents say they prefer “democracy,” they may actually be saying they prefer American wealth, though not its “corrupt” culture (revealed in other questions). Unfortunately, Pew did not explore what people mean by the English word, “democracy.”

Pew could have asked Muslim respondents in Egypt whether they wanted Sharia law to be law of the land, but for some reason chose not to do that. Curiously, Pew did ask about Sharia law when it polled Muslims in Sub-Sahara Africa the year before, though chose to eliminate that question from the poll about Muslims elsewhere. Perhaps, it was the conflicting results which prompted the sponsors to drop the Sharia law question, for they challenge the view that democracy is widely revered among Muslims.

The specific question was: “And do you favor or oppose the following: making Sharia or Islamic law, the official law of the land in our country?”

What’s interesting about the results is that large majorities of Muslims in many of the countries express a preference for “democracy,” but then also express a preference for Sharia law.

In Nigeria, for example, 68% of Muslims say democracy is the most preferred of any type of government, but 71% of these same Muslim respondents also say they want Sharia law to govern their country. The same pattern – about two-thirds or more of respondents opting for democracy, and then two-thirds or more also choosing Sharia law – was also reported in several other countries as well: Kenya, Djibouti, Mali, Ethiopia, and Uganda.

It is worth noting that large majorities of Christians in these Sub-Saharan countries also opt for the Bible being the law of the land, even as large majorities of these same respondents say democracy is preferable to any other type of government.

What these results suggest is that people in these countries do not understand “democracy” in the same sense that Westerners do. In the Western concept, democracy and the imposition of religious law by religious leaders are diametrically opposed concepts.

The democratic form of government is more than majority rule and election of leaders. It is a culture that also requires respect for dissent and protection for minorities. Also, the laws in a democratic government are determined by representatives elected by the people, or in many cases by voters themselves. That is not the case with religious law, which is not determined by input from voters, but is imposed by religious leaders.

Support for Extreme Punishment Consistent With Some Interpretations of Sharia Law

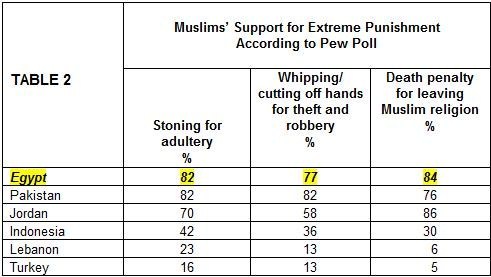

While Pew did not ask Egyptian Muslims about Sharia law, Pew did ask about three types of punishment for crimes. The results suggest that Egyptian Muslims are very much in favor of the harsh punishments often imposed (in practice) by Sharia law: stoning adulterers to death (82%), whipping people or cutting of their hands for crimes like theft and robbery (77%), and imposing the death penalty for leaving the Muslim religion (84%).

(Credit: Pew Survey)

The Egyptian percentages are among the highest for Muslims in the Middle Eastern countries (plus Indonesia). It’s also worth noting that the lowest support for extreme punishments is found in the three countries (Turkey, Lebanon, and Indonesia) that have – at one time or another – experienced relatively democratic governments.

The Egyptian percentages in favor of extreme punishments are also significantly higher than any of the percentages in the Sub-Saharan countries. Among the latter, the Djibouti Muslims are closest to the Egyptian Muslims – though the Djibouti percentages are still significantly lower: 67% of Djibouti Muslims favor stoning adulterers, 70% favor cutting off thieves’ hands, and 62% support the death penalty for leaving Islam (from 7 to 22 points lower than the Egyptian percentages).

A significant point is that among the Sub-Saharan countries, the Muslims in Djibouti are also the most in favor of Sharia law (82%). If high support for extreme punishments is correlated with support for Sharia law, then the willingness of Egyptians to adopt some form of democracy may well conflict with those who prefer religious leaders – not voters – to prescribe civil law.

Caveats About the Poll Findings

Polls need to be viewed skeptically, for at best they are blunt measuring instruments. The Pew poll is no exception. It is fraught with all sorts of limitations, not the least of which is the difficulty in translating English into other languages, and putting the concepts of Western culture into the framework of Islamic and Middle Eastern cultures.

The poll results just described do not necessarily mean Egyptian Muslims aren’t ready to accept democracy. They do, however, challenge the earlier Pew interpretation that about six in ten Egyptian Muslims genuinely prefer “democracy” – at least democracy as it is meant in Western culture – over any other form of government. Instead, it appears that a “democratic culture” has yet to be established in Egypt, though the evidence is thin either for or against that conclusion.

The uprising against Hosni Mubarak may not be a call for democracy as much as it is a revolt against long years of oppression, corruption, and economic stagnation or decline under Mubarak. While the public protests have been able to force him out of office, other forces are more likely than Egyptian public opinion to determine the nature of Egypt’s transition from his rule to rule by other leaders.

Still, it’s an important issue – the extent to which the Egyptian public genuinely wants the messiness of democracy or may be willing to accept instead a more theocratic-oriented form of government. The protests make clear that Egyptians were no longer willing to accept Mubarak’s authoritarian rule, but the Pew poll doesn’t tell us what alternatives they will be willing to embrace or tolerate. Democracy may be one. But theocracy may be just as likely.

David W. Mooreis a Senior Fellow with the Carsey Institute at the University of New Hampshire. He is a former Vice President of the Gallup Organization and was a senior editor with the Gallup Poll for thirteen years. He is author of The Opinion Makers: An Insider Exposes the Truth Behind the Polls (Beacon, 2008; trade paperback edition, 2009). Publishers’ Weekly refers to it as a “succinct and damning critique…Keen and witty throughout.”