(Credit: Pixabay)

In a recent New York Times op-ed, Mark Hannah, a senior fellow at the Eurasia Group Foundation, presents a case for the United States to withdraw from Afghanistan. I offer no commentary on the general merits of his argument, except when he cites public opinion polls to bolster his case. The notion that the general public has a meaningful opinion on U.S. strategy in Afghanistan is simply not plausible.

Rather than providing a clear direction for policy makers, the public holds what might best be described as a “permissive opinion” about the issue – essentially most Americans will go along with whatever decision the president makes. Suggesting otherwise is misleading.

Hannah’s argument for U.S. withdrawal comes as the Biden administration faces a May 1 deadline, negotiated with the Taliban last year, to remove all its troops from Afghanistan. The agreement, however, is controversial. Foreign Policy reports that many career military and intelligence officials are vigorously opposed, fearing that a “premature withdrawal could potentially leave the United States back where it started, threatened by a Taliban-dominated host nation for al Qaeda.”

On the other hand, like Hannah, the Washington Post’s David Ignatius argues that Biden really has no choice but to “close the book” on Afghanistan, given the widespread consensus that further fighting there will not lead to anything that can be called “victory.”

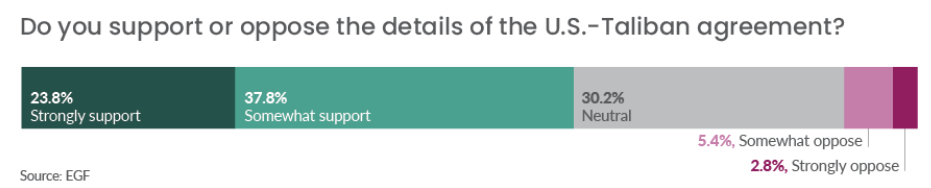

To bolster his argument for withdrawal, Hannah cites polling that “my colleagues have conducted,” showing that “the American people support the details of the U.S.-Taliban agreement by six to one.” Well, yes, they more or less do. But it’s not relevant to the question that faces the current administration. Here’s the polling data that Hannah reports:

According to the poll report, respondents were first presented with the details of the U.S.-Taliban agreement, and then asked the above question. Given that the U.S. government and the Taliban arrived at the agreement, it would be surprising if respondents did not also agree.

Note, however, that only 24% “strongly” supported the agreement. Another 38% said they supported it “somewhat”, for a total of 62%. Only about 8% said they opposed the agreement, including just 3% who felt “strongly.” Another 30% were “neutral.”

As described on this site about a similar situation involving Afghanistan, only people who have “strong” opinions can be characterized as engaged in an issue. Respondents will often say they “somewhat” support or oppose a policy proposal, but research has shown that such respondents typically don’t care one way or the other. In this case, just 27% feel strongly about the U.S.-Taliban agreement – 24% in favor, 3% opposed – leaving the rest of Americans essentially unengaged on the question of the agreement.

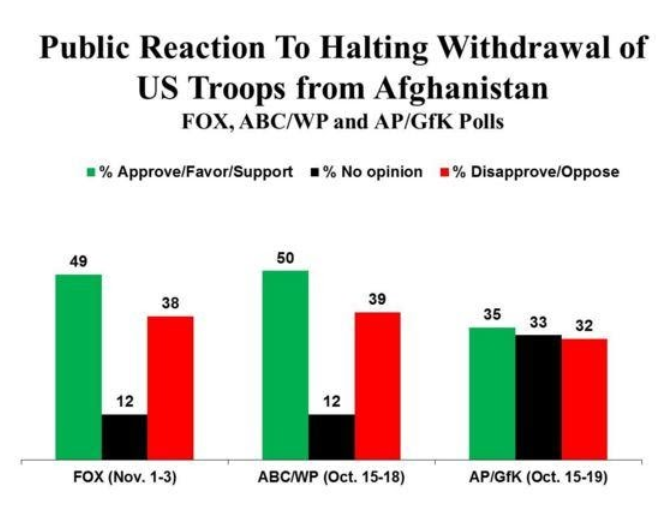

In 2015, there was a similar situation involving Afghanistan, when President Obama announced he was halting the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan. He had promised that during his presidency he would end the war there, but in the announcement he argued that it was vital to the nation’s security that the U.S. needed to stay there longer.As posted on this website, two polls each showed an 11-point margin of support for the decision – Fox by 49% to 38%, and ABC News/Washington Post by 50% to 39%.

In both those polls, a forced-choice question format was used, where the respondents are not offered an explicit “no opinion” option. The Associated Press/GfK poll did provide such an option, which explains why their “no opinion” result is almost three times greater than the other two polls.

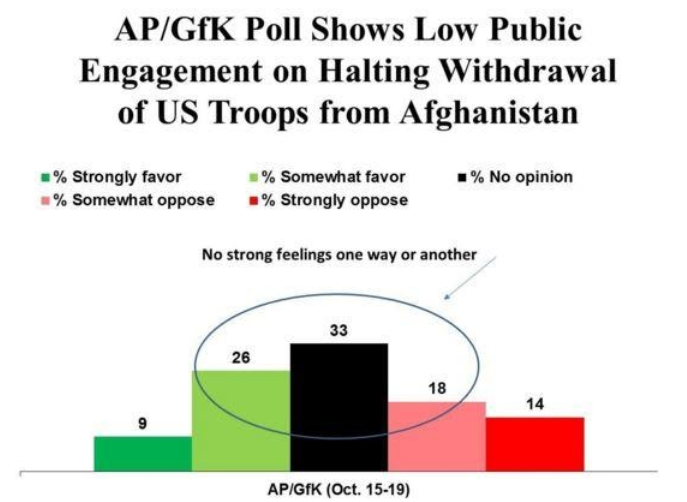

The AP/GfK poll also followed up by asking how strongly respondents felt about the issue. Those results are shown below.

Note that just 23% of the sample expressed a “strong” opinion – 9% in favor of Obama’s decision to halt withdrawal, 14% opposed. The rest of the sample – 77% — had no strong feelings one way or the other.This lack of engagement in foreign policy is typical.

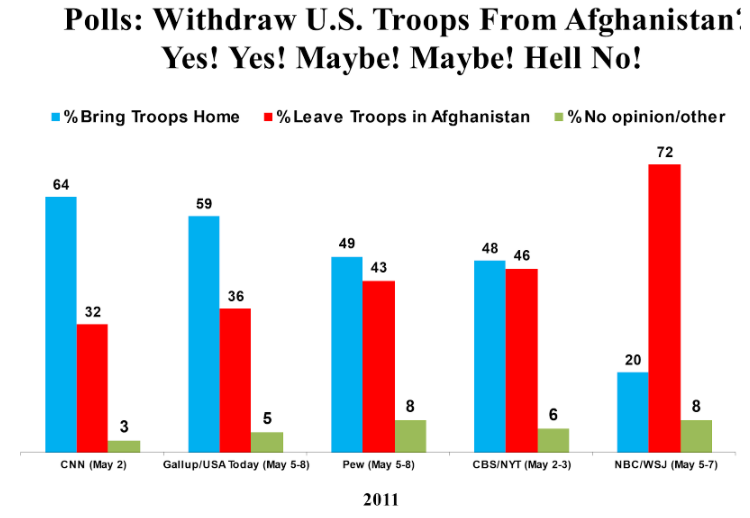

In 2011, after the U.S. government killed Osama bin Laden, numerous progressives called for withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan. Several polls were conducted to measure the public’s views. As shown below, the results varied widely, from a 32-point margin in favor of withdrawing troops to a 52-point margin opposed.

The explanation for these large differences, of course, is found in different question wording. But the fact that small changes in question wording can produce such disparate results is evidence for how unengaged the public was on this issue. Respondents were basing their views on what information they could infer from the way the question was worded rather than from any opinions they had personally developed from a previous engagement in the issue.

Permissive Opinion

When a substantial segment of the public is unengaged on an issue, in effect the public has a “permissive” opinion. There is no strong majority either in favor or opposed, thus “permitting” the government to take whatever action it deems best.

As I argued earlier this year, the public is particularly unengaged on foreign policy issues. On Afghanistan, polls over the years reaffirm that public opinion is not a sure guide to strategy.

There are apparently good reasons for the Biden administration to delay removing troops from Afghanistan, and good reasons for it to abide by the May 1 deadline. Whatever those reasons, they are independent of what polls might show about the views of a mostly unengaged public.