(Screenshot, Al Jazeera web site)

Qatar Broadcaster Failed to Protect Its Journalists by Skirting Permits and Broadcast Licensing Laws: Lawyer

After three of its journalists were arrested in Cairo in Dec 29, 2013, Al Jazeera has fed a global media blitz to free them. The state-owned Qatari network has stood on arguments of press freedom and human rights protections to fight charges that the journalists operated without press credentials or licenses and spread false news that promoted political dissent.

But iMediaEthics has uncovered strong evidence that Al Jazeera Network has, in fact, been undermining its imprisoned journalists—who worked for Al Jazeera English—with underhanded and perhaps criminal actions in Egypt.

Behind the campaign to free the journalists—Egyptian-Canadian Mohamed Fahmy and Australian Peter Greste, both of whom received seven-year prison sentences, and Egyptian producer Baher Mohamed, who was given 10 years—evidence indicates another campaign to incite pro-Mohamed Morsi demonstrations and support the Muslim Brotherhood at the expense of their detained journalists.

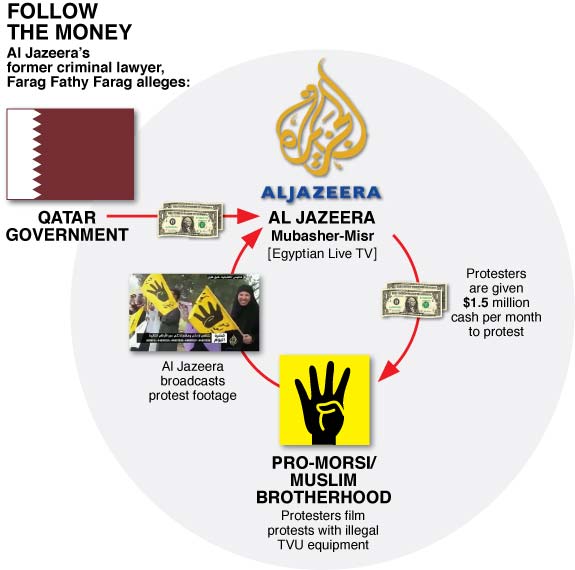

The network paid people from around Egypt essentially to play protesters on television, in a potentially hazardous deception. Hired “collaborators” got equipment to film staged demonstrations and send, with portable broadcast equipment (TVUs), protest footage to air on Al Jazeera’s Mubasher Misr Channel [translated as Egypt Live] from Doha.

Farag Fathy Farag, a former criminal lawyer for Al Jazeera, told iMediaEthics the network deposited $1.5 million in his bank account with instructions to pay Egyptian protestors cash for staging demonstrations for broadcast on Al Jazeera’s other channel, Mubasher Misr [translated as Egypt Live].

Asked about the charges Farag levied, Al Jazeera’s lawyer in New York, Frank W. Ryan of DLA Piper, wrote in a Sept. 25 letter to iMediaEthics that “any allegations” Farag made “are false”. Ryan provided no evidence to support this sweeping statement and declined to respond to follow-up questions.

Egypt, by contrast, is taking these revelations seriously. The International Cooperation Office of the Egyptian Prosecutor General confirmed by email to iMediaEthics that “the Egyptian Prosecutor General will verify allegations by Mr. Farag by judicial investigation.”

Previously unreported turmoil has sandbagged the three journalists’ legal representation despite the deep wealth of Al Jazeera’s owner, Qatar’s ruler, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani. Curiously, no powerful London law firm, like the one Al Jazeera hired to sue Egypt in April, backs a string of Egyptian lawyers who, in seemingly endless succession, have been fired or quit, iMediaEthics has learned. The exodus led off with criminal lawyer Farag dramatically resigning in court on May 15, claiming Al Jazeera was undermining his clients’ case, as first reported by ABC Australia on May 9.

——————————————————————————————————————–

Story highlights

- Farag Fathy Farag, a former criminal lawyer for Al Jazeera, says the network deposited $1.5 million in his bank account with instructions to pay protestors cash for staged demonstrations.

- Lawyer says Al Jazeera pays thugs to commit violence against Egyptians in order to blame the security forces.

- Al Jazeera dismisses former lawyer’s charges with a blanket denial.

- Egyptian Prosecutor General will “verify by judicial investigation” Farag’s allegations.

- Contrary to Al Jazeera’s claims of indiscriminate crackdowns on its network’s reporters, six credentialed Al Jazeera English [AJE] employees in Egypt were never arrested or detained and still work in Cairo.

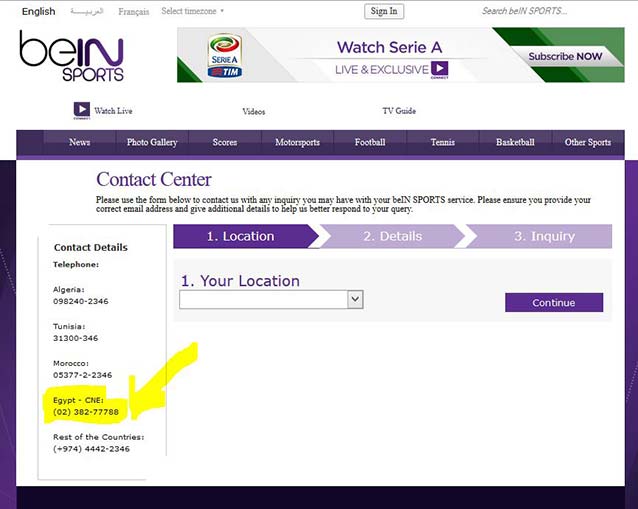

- AJE has the same office/studio space it always rented and AJ Network still broadcasts its two BeInSports channels in Egypt.

- Chaos has stymied the criminal representation of the three detained journalists, leading to a revolving door for lawyers who quit or are fired.

- Al Jazeera won’t disclose whether the imprisoned men have criminal lawyers now.

——————————————————————————————————————-

In an exclusive video interview, Farag tells iMediaEthics that Al Jazeera has undermined the journalists’ legal case by, not only operating a channel illegally, but also by funding pro-Morsi protests after millions of citizens hit the streets June 30, 2013 demanding the then president leave office one year following Morsi’s election.

| Former Al Jazeera lawyer, Farag Fathy Farag, Says Al Jazeera attempted to launder money and paid people to stage protests. [Exclusive interview by iMediaEthics] Find Transcript Here> |

When Egypt Central Bank subsequently blocked Qatari accounts, Farag tells iMediaEthics Al Jazeera deposited $1.5 million into his bank account in three transactions. Further, Amin Saad Abdulla, Executive Director & General Counsel at Al Jazeera Media Network, is one among others who Farag says explained that Al Jazeera headquarters wanted people to pick up cash payments at his office.

Farag soon discovered that the money, which the network expected to give him monthly, was not for Al Jazeera staff, as Farag was initially told. Rather, it was intended to pay pro-Morsi, pro- Muslim Brotherhood protesters to stage demonstrations throughout Egypt for Al Jazeera “collaborators” to film for broadcast on Mubasher Misr, the network’s pirate TV channel that Egypt shut down for operating without a license.

———————————————————————————————————–

Credit: Graphic by Alberto Mena

Farag’s withdrawal from the case, along with two other lawyers’, was quickly followed by resignations or firings (neither would say) by Fahmy’s lawyer, Khaled Abu Bakr, and Yousri al-Sayyid. AJ’s legal team in Doha, Qatar instructed Farag via a May 12 email, that al-Sayyid would replace him — even though al-Sayyid wasn’t a criminal attorney, iMediaEthics learned.

Al Jazeera declined to answer iMediaEthics’ questions about if the journalists even have criminal or other attorneys at present.

Al Jazeera has spent freely on its media blitz, buying sponsored tweets (#FreeAJStaff) and taking out a full-page ad Sept. 24 in the New York Times. (Sponsored Tweet: Al Jazeera English, @AJEnglish 3hr, Journalism is not a crime. Show your support for our journalists jailed in #Egypt. #FreeAJStaff. Please RT. Promoted by Al Jazeera English.)

Journalism is not a crime. Show your support for our journalists jailed in #Egypt. #FreeAJStaff. Please RT. https://t.co/YE6TUz0gkv

— Al Jazeera English (@AJEnglish) September 24, 2014

An international dream team of lawyers would be well within the network’s reach. Instead, the legal defense for the journalists has continually floundered. Media outlets from around the world have failed to dig any deeper into the Al Jazeera narrative, other than ABC AU’s May 9 exclusive interview with Farag.

Farag was widely quoted in the media reports about the May 15 drama as having emails that prove his charges against Al Jazeera. The Guardian reported: ” ‘Al-Jazeera is using my clients. I have emails from [the channel] telling me they don’t care about the defendants and care about insulting Egypt,’ he told the court.”

Yet on June 5, Farag told iMediaEthics that we were the first to ask to see the emails or to interview him after his resignation about the infighting with Doha or the revolving door for its legal team. That legal team had wanted to free the AJ English journalists by separating them, in perception and with evidence, from the AJ Arabic and AJ Mubasher Misr (Egypt Live) channels, now broadcasted from Doha.

Farag asserted, in iMediaEthics’ June 5, 2014 interview, that the deposit into his bank account and other financial activities by Al Jazeera in Egypt constituted crimes. He refused to participate in the money laundering scheme, he said, and returned the money, insisting proper taxes be paid to the Egyptian government.

iMediaEthics has emails that support Farag’s assertion that he returned large chunks of money to Al Jazeera. (See Oct. 30 2013 email exchange between Farag and Yousef Al Jaber, Al Jazeera’s Head of Cases & IP Legal Affairs & Contracts Department where two checks totaling $169,491 are confirmed received by Gamal Al Sharif, financial and administrative chief for Al Jazeera English).

In an email to iMediEthics last week, Farag’s law firm colleague explains more about what he did with the money and added: “please note that the amounts which Aljazeera transferred to Mr. Farag’s account was for purpose to be paid to the protesters, this is a crime.“

Farag expanded on his June 5 allegations in the video in this letter (read entire Sept. 29 letter here) and by phone, to include charges that Al Jazeera committed both violent and white collar crimes:

——————————————————————————————————————–

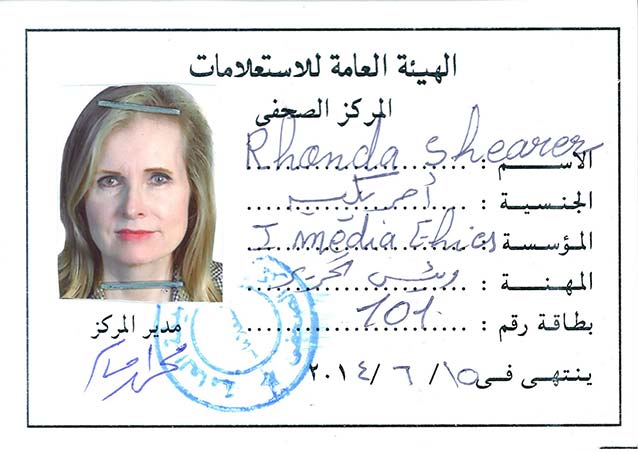

This is part one of iMediaEthics’ Investigative series on international media reporting on Egypt. iMediaEthics’ editor-in-chief and publisher, Rhonda Roland Shearer, spent much of May and June in Egypt reporting for this series. She worked with Nader Gohar and his CNC team to produce video reports for iMediaEthics.

Arabic Version of this story found on Almorakib.com

——————————————————————————————————————–

“We would like to emphasize that we have terminated the legal services contract between our office and Aljazeera channel in Doha due to our certainty that Aljazeera is supporting the terrorism with money and media…“

Farag continued: “Also we made sure [verified] that the demonstrations in Egypt are funded by Aljazeera as it paid for some of the unemployed [non-staff] money in return for doing fake demonstrations then filmed and broadcasted as a real, also we discovered that Aljazeera has contracted with thugs to kill the Egyptians during demonstrations and accuse security authorities.“

Through Ryan, its New York City attorney, Al Jazeera has declined to answer iMediaEthics’ specific questions about whether the network attempted to induce its attorney to pay protesters and collaborators to stage news or if they had the required licenses. None of our other questions were addressed. Fully a third of Ryan’s brief letter is reaffirming of Al Jazeera’s commitment to legally “doing all it possibly can“ to “protect these journalists“ and “everything within its power to secure their release as soon as possible“ while “ensuring they are properly represented.” (See entire Sept. 25 letter here)

iMediaEthics sent Ryan’s letter to Farag for comment. Farag’s Sept. 29 letter, cited above, followed.

Why No Press Credentials for Fahmy, Greste and Mohamed?

“I have been with Al Jazeera for three months, and I asked more than once, ‘Is our legal situation all sorted in Egypt?’ and they said, ‘Yes, legally everything is in order as Al Jazeera English.’ They told me not to worry.“

That’s what Mohamed Fahmy told police officers during the Dec. 29, 2013 Marriott Hotel room raid where he and Peter Greste were arrested.

Fahmy admits during the videotaped police questioning that he and Greste had no press cards.“We submitted the paperwork and we are still awaiting their response,” he says. (See full transcript of raid interview by police on iMediaEthics).

However, this was not true. iMediaEthics obtained the Dec. 23, 2013 application letter AJE sent to the Press Center for their annual renewal of press credentials. Any mention of the AJE drivers, bodyguards, correspondent Greste, producer Mohamed and bureau chief Fahmy were conspicuously and suspiciously (to the police) missing from the letter. (See letter from AJE to Press Center).

Only three names were listed–two cameramen and a “sound“ man. The so-called sound man was, in fact, Mostafa Samir Hawaa, the Al Jazeera English office runner, or what’s more commonly called the “tea and coffee boy“ in Egypt.

Fahmy fibbed, throwing Mostafa under the bus by telling police during the raid that he—the lowest-ranked office worker—was the head of finances for AJE and that he had his phone number to give them instead of naming the actual accountants– Gamal Al Sharif and Al Sharif’s boss, the AJ head of finance for Egypt. Fahmy also named his two cameramen listed in the letter.

This Press Center letter would later serve as evidence of deception in the criminal case, since in previous years AJE journalists and other workers were listed.

Also troubling for police investigators was that the AJE trio was hiding out in the Marriott rather than operating out of their seventh-floor offices/studios rented from a well-known broadcast journalist, Nader Gohar in the Cairo News Company (CNC) Ramses building. AJE still rents that space today.

Cairo News Company (CNC) rents office/studio space to Al Jazeera, yet AJ English continued to operate out of hotel rooms. (Credit: Cairo News Company website, Screenshot)

Cairo News Company (CNC) building located in Cairo, Egypt. (Credit: Google Maps)

Gohar, who was arrested during the presidency of Mubarak and knew how to stay out of prison, warned Fahmy not to hide, as discussed by Gohar in his iMediaEthics commentary posted today. It turns out that the Egyptian AJE staff with press cards were the smart ones, threatening to quit unless their names were submitted, as they feared arrest. Three AJE staffers managed to get the AJE finance man, Gamal Al Sharif–the same man who confirmed receipt of the two checks for $169,000 from Farag—to sign the Press Center press credential renewal letter. Three others got their press cards by other means. It is a mystery why Doha did not authorize naming everyone and why Fahmy did not insist on the same protection.

The fact that Al Sharif, the finance man, and not the bureau chief—which is the typical protocol—signed the Dec. 23, 2013 year-end renewal Press Center letter, also raised suspicion.

To make matters worse, the then-head of AJE Channel, Abdullah Mussa, took a hasty flight to Doha after the earlier Sept. 2 raid that preceded the Dec. 29 Marriot raid that ensnared the trio. We asked the network why the head of the Al Jazeera English channel on the same day of the raid decided to fly to Doha without informing co-workers, let alone Cairo authorities. They declined to answer. (See iMediaEthics email exchanges with Al Jazeera)

The AJE response to the government’s previous July 3, 2013 raid also did not include demanding through a local lawyer that confiscated equipment be returned, as Gohar advised.

Instead, the remaining AJE team was left rudderless. It was the lowest-ranked worker, the tea and coffee boy, Mostafa–not a high-paid Doha executive– who bravely led the way and stayed by his post in the Ramses AJE office on the seventh floor. He cleaned the office, found and shuttled papers to the Press Center and ferried files to lawyers, acting stalwart in his efforts to help get equipment returned and his colleagues out of detention.

Don’t Be Stupid, Get Press Cards and Permits

If you go to Egypt to do reporting, go to the Press Center and get a press credential. You need a letter from your embassy, another letter from your media outlet and a CV. This author’s press card is below.

Author’s Egyptian Press Credential (Front)

Author’s Egyptian press credential (back)

Gohar further advised iMediaEthics what is required of any media outlets he helps through Cairo News Company. AFP, AP, CNN, BBC, Reuters, etc., all follow the laws. As a result, their reporters aren’t arrested for covering Egypt. Gohar explained:

- They should declare an office in Cairo to the Egyptian Press Center.

- They beam footage out of the country using the Internet.

- Some live events need satellite transmitting equipment and here either they use a local company or they get their own satellite transmission equipment where they need permission from NTRA (Telecom regulator) and Egypt TV.

He warned me when iMediaEthics employed his services that “everyone needs a filming or production permit, and there is a difference”:

- If you have an office representing your channel or agency in Cairo or you’re a resident journalist, you get a permanent permission.

- If you’re a visiting journalist, you should ask for a permit.

According to Gohar, here is what’s wrong, in a nutshell, with Al Jazeera English:

- English got an authorized office in Cairo and its staff got Egyptian press cards. When the other banned Channels of Aljazeera used their footage, police came to investigate and confiscated their equipment [July 3, 2013] and you know the rest of the story.

- Fahmy and Greste arrived in Egypt, and they used the two accredited cameramen but they didn’t go to the Press Center. They didn’t get the press cards, and they didn’t ask for filming permits –which means they didn’t follow either the rules for a visiting journalist or a resident journalist.

Al Jazeera apparently acted above the law and its journalists are paying the price.

Mubasher Misr Had No License to Broadcast; Al Jazeera Accused of Piracy

If you start a channel originating from Egypt, that too requires a license, just as in the United States. Al Jazeera knows a license for a TV channel is required. It bought an existing TV channel for $500 million that already had a license in the United States, Current TV, and rebranded it Al Jazeera America. It went live on August 20, 2013.

As if it were an irresolvable, “he said, she said” charge, the media reported the Egyptian government accused AJ Networks of operating without a license without asking AJ whether or not it had such a license.

Lacking from coverage was any context of how governments typically regulate their TV and radio airwaves. Starting a channel in Egypt without a license, as all evidence indicates Al Jazeera did, makes you subject to fines and criminal penalties. It’s the very definition of a pirate TV broadcast operation.

If Al Jazeera had proper licensing, it would behoove the network to disclose this fact with documentation. Both the AJ Media Network headquarters and its New York attorney declined to respond to iMediaEthics questions about having proper licenses.

Gohar told iMediaEthics the basic law in Egypt to launch a satellite channel:

- Declare Public Limited Company (PLC) with capital of 30 million Egyptian pounds.

- Hire studio/offices at the Media City free zone area.

- Hire a channel on Nilesat satellite.

- After completing the above steps, you get the approval of the channel from the investment authority.

Nader said, “They [Al Jazeera] did nothing from above except hiring the channel from Nilesat.“ AJ’s former lawyer Farag addresses AJ piracy, breathtaking in its audacity. See part two of iMediaEthics June 5, 2014 video interview with Farag below.

| Former Al Jazeera lawyer, Farag Fathy Farag, Says AJ operated illegally in Egypt endangering its journalists. [Exclusive interview by iMediaEthics] |

Was Al Jazeera Illegally Broadcasting as a Pirate?

As in the United States, not having a license for broadcasting a new channel is piracy, a crime. Yet, no one in the media insisted Al Jazeera produce its own license for verification or checked Egyptian broadcast statuses. Instead, reporters swallowed AJ’s line that its journalists were caught in a capricious crackdown.

Despite its claims of an Egyptian government vendetta, Al Jazeera still broadcasts a sports news channel in Egypt. Note in these BeInSports screenshots below, Al Jazeera is the owner of beINSPORTS and is operating in Egypt.

beIN SPORTS, broadcasted in Egypt, is a part of Al Jazeera Media Network. (Credit: SatandPCGuy.com, Screenshot)

beIN SPORTS directs callers to an Egyptian telephone number (Credit: beIN SPORT website, Screenshot)

Farag’s Last Straws

After dealing with all of the above, the final straw for Farag came when AJ hired a big London law firm and filed a lawsuit against Egypt, with much fanfare, only two weeks before (May 15) his most important date in the trial– the final pleading for Greste and Mohamed. By this time, Khaled Abu Bakr was representing Fahmy. Mr. Khaled told iMediaEthics by phone last week: “I am off the case” and “I am sorry. I am not allowed to talk.”

In Farag’s opinion, the lawsuit was a complete sham and publicity stunt. AJ can’t claim damages for its channel being shut down: Egypt closed it for operating illegally.

That AJ launched the suit without consulting him infuriated Farag. The timing of AJ’s lawsuit could not have been worse. Farag had repeatedly discussed with Al Jazeera’s main office in Doha, to no avail, that their single defense for the three men was to convince the judge that Al Jazeera English was completely separate from Mubasher Misr and that they were not working with the Muslim Brotherhood to help their cause.

Former Al Jazeera lawyer, Farag Fathy Farag, represents jailed AJ reporters in court. (Credit: Screenshot detail from Farag Law Firm website, AP Photo).

Following Farag’s complaint to Al Jazeera that the lawsuit would hurt his clients—a complaint that got no results—he went public and did a brief interview with Australia’s ABC channel that aired May 9.

Afterwards Farag accidentally received an AJ internal email complaining about that interview. It suggested that AJ ask him to keep his mouth shut and, possibly, issue an apology and retraction. Farag, fed up, submitted his formal resignation for early 2015, timed to allow a smooth transition in the case. Email exchanges from April 7 to May 17 show that the network, with c.c.’s to the “Al Jazeera Crisis Management’’ team, demanded Farag quit immediately and send his records to lawyer Yousri al-Sayyid (who would also soon be fired or quit). On May 15 Farag announced his resignation in a Cairo court, listing to the judge the multiple ways AJ was harming his clients’ criminal case.

Earlier emails, April 7, 2014 among them, show that Farag urged AJ to change its editorial bias and the blatant errors it was broadcasting on Mubasher Misr. The false reports were never corrected, according to Farag and his lawyer colleague. Examples of fake news in the emails include a false report broadcast on Egypt Live that quoted Farag asking to transfer the journalists from the tough “Scorpion Unit” to the Tora prison. In fact, from the start, they have only been housed in the Tora prison (where inmates can arrange to have food delivered).

A toxic mix was building for the journalists’ case. Misinformation broadcast on Mubasher Misr about Farag, his clients, the police investigation and the trial only served to cement the prosecution’s, the public’s and the judge’s belief that AJ English was one and the same as Mubasher Misr. This wasn’t journalism, according to Farag. Indeed, Egyptians commonly call Mubasher Misr the Muslim Brotherhood’s “propaganda channel”.

The Associated Press reported on Sept. 13, 2014:

“The network has denied the allegations. But its Egyptian branch, Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr, devotes its entire broadcast to covering near-daily, scattered demonstrations by Morsi’s supporters and frequently hosts pro-Islamist commentators.“

The same AP report echoed Farag’s charge that AJ Mubasher Misr (Egypt Live) obtains its content from Egypt by “collaborating with freelancers and using amateur video“ and that the channel “has continued to broadcast using its studios in Doha, Qatar“. Farag’s accusations provide a convincing explanation as to how AJ pays and equips these “collaborators.”

Farag told iMediaEthics on June 5, 2014: “Al Jazeera pays random people in every region of Egypt 3,000 pounds an hour on top of providing them with the TVU equipment. They use people’s misery. And they spend incredible amounts of money on that. I know that for a fact.“

The Guardian reported audio clip evidence was presented by prosecutors where “someone could be made out saying that they were paid by al-Jazeera’s Arabic wing to send footage to the channel.“

By July 3, 2013, a raid closed Al Jazeera English, because of Mubasher Misr, and resulted in the arrest and release after a couple hours of 27 AJE employees for not having proper work permits.

After the AJ raid occurred, local Egyptian media reported 27 journalists were briefly detained and a few were deported.

MORE RELATED TO THIS STORY

The comingling of staff and operations in Cairo and Doha doomed any practical separation among the channels.

Gohar repeatedly cautioned his tenants not to broadcast AJ English footage over the Arabic or Mubasher Misr channels. Yet inevitably the Cairo and Doha operations would do just that.

The Egyptian public would complain to authorities about watching reports on nearby demonstrations when no such events were taking place. Demonstrations labeled Turkish unrest, were shown at other broadcast times– with the same people dressed in the same clothes– but re-labeled Egyptian unrest .

By July 8, 22 Al Jazeera journalists quit in protest.

The international Arabic Newspaper, Aawsat, reported: “Al-Jazeera correspondents Hajjaj Salama and Wissam Fadel resigned, news anchor Doha Al-Zohairy joined the list as well. Zohairy told Asharq Al-Awsat: “I have been considering resigning since about a week after coverage from the events of June 30 was deliberately excluded.”

With Doha’s backing the Al Jazeera English channel went underground (or so it thought) in hotel rooms and cafes, but was still paying rent on its seventh floor office/studios near Ramses, the location Fahmy also described in the police interview as the Al Jazeera headquarters. Why? iMediaEthics asked but Al Jazeera is mum.

Al Jazeera had no trouble marshalling a powerful international law firm to sue Egypt at the worst moment for its journalists. So why hasn’t the network brought those resources to bear in mounting their legal defense?

In his Sept. 29 letter to iMediaEthics, Farag stated: “I can tell you that when we withdrew from representing Peter and Baher in the case, Aljazeera refused to appoint another professional criminal lawyer for their detained journalists and told them that the lawyer of the Muslim Brotherhood [defendants] will represent instead.” If true, this is an obvious disaster for the detained journalists.

Meanwhile, AJ’s global campaign, “Journalism is not a crime,” continues. Media outlets worldwide have disseminated AJ-sponsored tweets. Journalists and free speech advocates have photographed themselves with taped mouths.

Many of them surely presume that AJ has done its part, operating legally and in good faith, to ensure the safety of its employees in Egypt. But the network’s actions show otherwise. The network spares no expense when suing Al Gore and Egypt. Yet no such action to retain international legal fire power has been taken, despite its lawyer’s pat assurances to iMediaEthics that the network is doing its all.

The tape can come off: AJ needs to answer questions.

UPDATE: Correction: Oct. 17, 2014, 2:18 PM: Due to editing errors, the Dec 29, 2013 arrest month and the Al Jazeera America channel name were incorrect and are now corrected. In addition, the earlier Sept. 2 raid that preceded the Dec 29 one was cut from a sentence during editing. Thanks to journalist, Mohannad Sabry, for letting us know. Sabry also wrote about Al Jazeera’s failures to their journalists on The Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy’s web site, Oct 15, following this report.

Editor’s Note: iMediaEthics attempted to contact the Muslim Brotherhood for comment through its website and received no response. The Australian embassy contacts who Farag was in communication with (offering to work for free, if done independently from AJ after he quit) declined to comment. Also, iMediaEthics contacted AJ’s London law firm, Carter Ruck, and wrote and called multiple times to follow up with AJ’s New York City lawyer but did not receive a response following his single communication, the Sept. 25 letter.

Lindsey N. Walker contributed to research, reporting and production in New York City.

Jasmine Bager, Anicée Gohar, and Shadi F. George translators for documents

Video Credits

Rhonda Roland Shearer, producer

Lindsey N. Walker, production assistant

Cairo News Company:

Soha Alaa, video editor, translator

Gad Hashem, cameraman

Yasser Hosny, soundman

Anicée Gohar, translator