New national poll finds as many as two of three Americans have no opinion about Iran nuclear deal and three out of four Americans don’t even know what the deal is all about

A new poll by iMediaEthics, conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International August 6-9, 2015, finds a large majority of Americans clueless as to what the nuclear deal with Iran is intended to accomplish.

Only 8 percent of Americans say they know a lot about the agreement, 32 percent say “a fair amount,” while 59 percent say know they little or nothing at all about it.

Half the sample of 1,000 respondents was given no information, but was simply asked if Congress should vote to support or oppose the agreement – 17 percent of this group said support, 24 percent said oppose, and a substantial majority, 58 percent, offered no opinion.

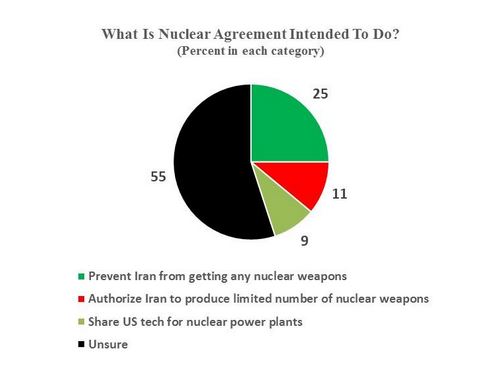

When this same group was asked what they thought the agreement is intended to do, just 25 percent accurately said it was intended to prevent Iran from getting any nuclear weapons. The rest said the intent of the agreement was either to authorize Iran to produce a limited number of nuclear weapons (11 percent), or to allow Iran to share U.S. nuclear technology to build nuclear power plants (9 percent) – or they didn’t know what the agreement is intended to accomplish (55 percent).

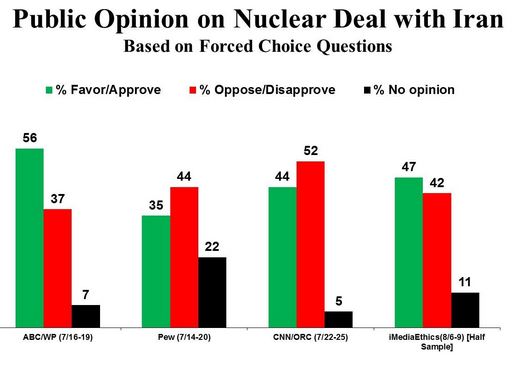

This picture of the American public, as overwhelmingly disengaged and uninformed about one of the most pressing issues currently facing the country, contradicts three recent polls – separately conducted by ABC News/Washington Post, CNN/ORC, and Pew – which portray the public as highly engaged, with the vast majority of Americans supposedly able to express meaningful opinions.

All of those polls used forced-choice questions that provide no explicit “unsure” option, and thus pressure respondents to come up with an opinion, even if they don’t have one. The iMediaEthics poll included a forced choice question on one half the sample, and – like the other polls – was able to create the illusion that the vast majority of the public has a meaningful opinion on the issue.

Both ABC/WP and the half sample of iMediaEthics polls found more people in support of, rather than opposed to, the agreement. That’s undoubtedly a reflection of question wording. The half sample of the iMediaEthics poll parroted the introduction given by ABC/WP, which explained that the agreement was intended to prevent Iran from gaining nuclear weapons and that international inspectors would monitor Iran’s activities. In contrast, Pew and CNN/ORC simply asked respondents if they favored or opposed the agreement, but provided no details.

Avoiding the Use of Forced Choice Questions

A more realistic approach to measuring public opinion is to ask a policy question that is not forced choice, but instead offers the respondents an explicit “don’t know” option. When that approach is used, many people are willing to admit that, in fact, they don’t have an opinion.

That type of question was included in NBC/Wall Street Journal poll, the CBS News poll, and half the sample of the iMediaEthics poll.

Note that with the use of a question that offers respondents a “don’t know” option, the percentage of Americans with no opinion is estimated to be as low as one-third (NBC/WSJ) to almost a half (CBS) to a high of two-thirds (iMediaEthics, including the intensity measure).

Almost certainly, the major reason why the “non-opinion” measures by each of the polls differ so substantially is that each polling organization provided a different amount of information to their respondents. NBC/WSJ gave a long explanation about the agreement, while CBS provided a shorter explanation, and iMediaEthics provided no explanation at all for this half sample.

NBC/WSJ question wording:

“As you may know, an agreement has been reached between Iran and a group of six other nations, including the U.S. The agreement attempts to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon by limiting Iran’s ability to produce nuclear material and allowing inspections into Iran’s nuclear sites in exchange for reducing certain economic sanctions that are currently in place. Do you support or oppose this agreement or do you not know enough to have an opinion?”

CBS News question wording:

“Recently, Iran and a group of six countries led by the United States reached an agreement to limit Iran’s ability to make nuclear weapons for more than a decade in return for lifting economic sanctions against Iran. From what you’ve heard or read so far, do you approve or disapprove of the recent agreement with Iran, or don’t you know enough about it yet to say?”

iMediaEthics question wording for half the sample:

The first question in the poll asked how much respondents felt they knew “about a recent agreement involving the United States and Iran’s nuclear program,” and then asked: “Based on what you’ve heard or read in the news, do you think Congress should support or oppose the agreement – or are you unsure?”

Even though all three polls offered a “don’t know” option, by providing an explanation about the agreement, both NBC/WSJ and CBS were able to elicit a greater opinion response than iMediaEthics.

The problem with providing such information, however, is that once the sample of respondents has been given the pollster’s specific limited view of the issue, that sample no longer represents the larger population – which has not been informed about what the Iran agreement is all about.

Also, different explanations lead to different poll results. Some will lead respondents in one direction, some in another. No one explanation can be considered truly objective, so any attempt to “educate” the respondents invariably leads to biased results.

To measure opinion as it currently exists, rather than what it might be if all Americans were given the same explanation as respondents in a poll, it is crucial for the pollster not to taint the sample with biased information, as did these brief explanations.

Measures of Intensity

Although people can be given an explicit “don’t know” option, many will nevertheless come up with a response that they don’t really care about. They do this in the context of a poll, where in general they are expected to have opinions. They don’t want to keep saying “don’t know” to question after question, and instead will go ahead and make snap judgments to fulfill their perceived responsibility.

One way to see how committed people are to their own opinion is to ask if they would be upset if the opposite condition were to prevail from the one they just said they preferred. If they say they want Congress to vote in favor of the Iran nuclear deal, for example, but would not be upset if Congress voted against it, it’s reasonable to infer that the person really doesn’t care what Congress does.

The iMediaEthics poll initially asked half the sample whether respondents wanted Congress to vote for or against the agreement (“or are you unsure?”), and those results are shown in the previous graph: 17% for the agreement, 24% opposed, and 58% unsure. A follow-up intensity measure was asked of respondents who expressed an opinion. Those who said they wanted Congress to support the agreement were then asked how upset they would be if Congress voted against it. And those who wanted Congress to oppose it, were then asked how upset they would be if Congress voted for it.

People who said “very” or “somewhat” upset were classified as having strong opinions, while those who said “not too” or “not upset at all” were classified as not really caring how Congress might vote one way or the other.

The net result is that about 28% of those who opposed the deal said they wouldn’t be upset if Congress voted to support it, and about 15% of those who supported the agreement said they wouldn’t be upset if Congress voted against it.

Taking these intensity results into account, the results show that just 12% wanted Congress to vote in favor of the agreement and would be upset if Congress did the opposite, while 21% wanted Congress to vote against the deal and would be upset if Congress actually voted in favor of it.

That leaves two-thirds of Americans with no emotional stake in what Congress decides to do – they either have no opinion about the Iran nuclear agreement (58%) or have expressed an opinion but would not be upset if Congress did the opposite of what they said they wanted (9%).

Polls that taint the samples, by giving respondents limited information and using forced choice questions, can make it appear that the vast majority of the public is engaged in the issue and has an opinion about it. But a realistic picture of the American public suggests a situation quite at odds with that view.

Note: Methodology and topline for the iMediaEthics poll is here.

Updated 8/17/2015 12:29 PM EST