The Pig in a Garden: Jared Diamond and The New Yorker Series

Art Science Research Laboratory’s imediaethics.org is publishing a series of essays on the controversy surrounding Jared Diamond’s New Yorker article, “Annals of Anthropology: Vengeance is Ours.” The essay series titled,The Pig in a Garden: Jared Diamond and The New Yorker, is written by ethics scholars in the fields of anthropology and communications, as well as journalists, environmental scientists, archaeologists, anthropologists and linguists et al., and edited by Rhonda Roland Shearer, Alan Bisbort and Sam Eifling. *Note: Savage Mind people are leaving for the summer for research and find themselves unable to keep up with posting essays of , what has turned out to be, more contributors than anticipated. imediaethics.org will continue the series with the same editors. Alex Golub will comment from Papua New Guinea as time allows. Alan Bisbort’s essay is fifth in the series.

* * * * * * *

“That was how the Handa-Ombal war began,” writes Jared Diamond, as if dusting off an ancient Brothers Grimm fable. Rather than appearing in a work of fantasy, however, these words are found in a purported work of journalism called “Vengeance is Ours,” which was published in the April 21, 2008 issue of The New Yorker as hailing from “the Annals of Anthropology.”

Diamond’s tall tale, set in Papua New Guinea, continues: “An Ombal man found that his garden had been wrecked by a pig. He claimed that the offending pig belonged to a certain Handa man, who denied it. The Ombal man became angry, demanded compensation, and assaulted the Handa pig owner when he refused.”

What ensued was, according to Diamond, a wave of violence in the Southern Highlands region of Papua New Guinea that involved “between four and six thousand people” and escalated into a multi-year campaign marked by murder, rape, prostitution, theft and the sacrifice of pigs. Though it sounded far-fetched, Diamond’s tale of events in Papua New Guinea was—like a Brothers Grimm fable—compelling, dramatic and seemingly fraught with deeper meaning.

Upon closer inspection—and within the context of what has been learned in the year since the article appeared about Diamond’s research methods, backdated quotations and dubious journalistic ethics—the deeper meaning may not have been what the author intended. After reading and rereading this article several times, I am left with a single overriding image: the pig in a garden. And I still have at least two unanswered questions: Whose pig are we really talking about and what garden are we trying to evoke?

Spinning the Rough Diamond

First things first. No matter how their lawyers and publicists spin this rough Diamond, or even how it is spun inside a courtroom, The New Yorker screwed up royally by publishing the article “Vengeance is Ours.” Viewed purely as a work of journalism, it is certainly not worthy of someone who has been awarded a Pulitzer Prize, as has the bestselling author Jared Diamond. While I don’t pretend to have enough expertise in anthropology to comment on those aspects of the article—though some of the assertions seemed preposterous on their face to me (e.g., “buying” women with pigs? hiring prostitutes for warriors?), I know sloppy journalism when I see it. And this was shoddy goods.

As I revisited Diamond’s article while writing these remarks, I found myself facing the same grave doubts I had when I first read “Vengeance is Ours” in April 2008—before the pig feces hit the fan, so to speak. No matter how many times I’ve read it, though, my b.s. detector keeps going off. I am struck anew each time by how unreal the stories Diamond reported as fact really seem, how conveniently they mesh with his chosen theme (clearly stated in his subtitle: “What can tribal societies tell us about our need to get even?”), how dubious are the assertions, how weak the attributions and how much like a college professor the quotes attributed to this indigenous man, whose first language is not English, sound, e.g., “Boys and young men are prone to make such mistakes and hence are excluded from the stealth parties.” “And hence”? I doubt seriously if such expressions are even used around the Diamond household.

I was not surprised to learn from Rhonda Shearer’s and co-authors’ detailed chronicle at imediaethics.org that, although his article was labeled by the magazine as from “the annals of anthropology,” Diamond is not, in fact, an anthropologist. And from the anthropologists and other professionals who’ve responded on the website, I’ve also learned how flagrantly he abused other professions’ codes of ethics.

Diamond is apparently not a journalist either. A story of this magnitude—one that accuses named people of committing capital crimes—demands multiple voices and carefully cited, verifiable sources. If you accuse someone (or an entire tribe) of murder and rape, you had better have a massive backlog of evidence on your side. To wit: By the article’s second paragraph, Diamond has accused Daniel Wemp of initiating and essentially overseeing a three-year revenge spree that “took…twenty-nine more killings, and the sacrifice of three hundred pigs.”

Such bold assertions not only require evidence, they mandate that the reporter get permission from those quoted to use their material in a published work or, at the very least, to make them aware that such information will be used in a published work. None of these basic cornerstones of journalism were put in place.

Itemized Deductions from the New Yorker article

After my second and third passes through Diamond’s article, I gave up trying to weave a coherent tapestry of criticism. Instead, I simply itemized the most glaring of the journalistic failings as they hit me:

1. Diamond quotes only one source for his story. Even a high school newspaper sports editor would refuse to accept that from a stringer.

2. The quotations themselves seem unreal and stilted (see “and hence” above).

3. Why did The New Yorker, which makes a fetish of its fact-checking prowess—boasting that they even fact-check cartoons—do most of its fact-checking on Diamond’s story only after it appeared? Did its editors simply trust that Diamond had his ducks in a row because he’s a bestselling author? A professor? A nice guy? Is this standard operating procedure for contributors of similar high-profile status?

4. The New Yorker, from all appearances (and based on the exchanges between Shearer and the magazine’s staff, available on the imediaethics.org web site), did not verify quotes, dates or criminal assertions in Diamond’s article before it was printed. Ironically, the February 9, 2009 issue of The New Yorker included a self-serving, back-patting story by John McPhee that celebrated the magazine’s fact-checking prowess on his own work. In light of the scandal over Diamond’s article that was by then beginning to rear its ugly head, this McPhee piece seemed, at the very least, poorly timed.

5. Did Diamond not talk to a single person besides Daniel Wemp in PNG? (He told Science he only asked young Handas about names). Given that he states “between four and six thousand” people were involved in the violence, it stands to reason that there might have been other people with something to say about the events. It also stands to reason that if Diamond had talked to other people, he would have learned how farfetched were Daniel Wemp’s purported stories. If he didn’t talk to anyone else who witnessed the events, then he is guilty of journalistic negligence. If he did, and simply ignored the perspectives that were contrary to his chosen theme, then he is guilty of deception. Either way, Diamond is up a creek with this story.

6. And what of Henep Isum Mandingo? Diamond said, of a man he has never met, that Isum Mandingo had “organized the fight for the Ombals.” Further, “by accepting the official role known as ‘owner of the fight,’ Isum took responsibility for the killing…” And yet, Diamond never spoke to Isum (who is still living, and is suing Diamond and the New Yorker along with Wemp), nor did anyone at The New Yorker, even though he has just been named in “Vengeance is Ours” as responsible for major crimes.

7. Where does Diamond get his more general information about the habits and behaviors of “traditional New Guineans,” since no authorities are cited and he is not, as stated, an anthropologist? For example, where did he get his information to write a passage as simple as “Normally, a clan first tries to obtain vengeance within three weeks,” or a more complicated one, such as, “Traditional New Guineans, by contrast, have from childhood onward often seen warriors going out and coming back from fighting… If New Guineans end up feeling unconflicted about killing the enemy, it’s because they have had no contrary message to unlearn.” Statements like these had me screaming at the pages of the magazine, “Cite an authority, for crying out loud!” Diamond can’t just make these kinds of statements without explaining where he got them. One feels justified in concluding (right or wrong) that, without cited sources, Diamond was just making this up as he went along.

8. Finally, as a journalist, I saw another story, an investigative story, bubbling up beneath the particulars of this one. That is, an enterprising environmental reporter would be advised (ASAP!) to explore the connections between global environmental groups such as World Wildlife Fund and oil companies like Chevron and Oil Search Ltd. Why do they have such cozy relationships? Indeed, it appears from the descriptions in this article that the WWF and Chevron had a lucrative partnership. That partnership continues to this day with Oil Search Ltd., which bought out Chevron in PNG in 2003. On their Web sites, both WWF and Oil Search Ltd. describe each other as “partners.” Diamond is on the WWF board and describes himself as an environmentalist. Why then is he “green-washing” for oil companies? Shouldn’t the WWF (and, later, Oil Search Ltd.) be held partially culpable for allowing one of their employees (Daniel Wemp) to be exploited in this manner by a “guest” on their land? Do other members of (and/or contributors to) WWF know about these close ties to oil companies?

Given that I make a healthy portion of my living as a freelance writer for venues of print journalism—a portion that grows more sickly as such venues go out of business—I derive no pleasure in bashing one of the handful of print venues with a reputation for excellence. Among some of my favorite writers in the past have been regular contributors to The New Yorker—Joseph Mitchell, A.J. Liebling, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Calvin Trillin and Oliver Sacks.

This only compounds my frustration over Diamond’s story because it hurts not just the venerable reputation of this magazine but also the entire profession of journalism, past, present and future. People predisposed to slamming the press now have more ammunition to do so. They may feel justified saying, “Hey, if The New Yorker doesn’t bother to fact-check its articles, then can you trust any print journalism at all?” (I am not singling The New Yorker out on this score. Similar sentiments were voiced in the wake of the Jayson Blair scandal about the New York Times, the Stephen Glass scandal about the New Republic, the Mike Barnicle and Patricia Smith scandals about the Boston Globe, the Janet Cooke scandal about the Washington Post, the Jack Kelley scandal at USA Today, and so on).

Can We Have Our Journalism Back Now, Please?

At the risk of making this more of a political commentary than I intend, Diamond’s article, and the troubling issues it has raised about journalistic ethics, comes in the wake of eight years of massive failure by America’s “free press.” Journalists were so busy “embedding” themselves with subjects they should have been investigating (the White House, Wall Street, Halliburton, the Defense Department, the Justice Department, oil companies like Chevron, etc.) that they forgot the semi-sacred duties of their profession. No need singling out any venue or reporters for further abuse. Just add Jared Diamond’s name to a lengthy roll call; they’re all culpable.

If there is irony here, it is this: Seymour Hersh was among a handful of reporters who regularly broke through the propagandistic bubble that covered the eyes, mouth and ears of their colleagues in the American media in the last decade. During that time, Hersh published his most important dispatches in (drum roll please) The New Yorker.

A healthy democracy demands a free, unfettered and open press. And the field of journalism needs reportage in The New Yorker that can be trusted. Diamond’s “Vengeance is Ours” was a setback for both democracy and journalism.

Alan Bisbort is a freelance journalist and author. His books include Media Scandals (Greenwood Press, 2008) and “When You Read This, They Will Have Killed Me”: The Life and Redemption of Caryl Chessman, Whose Execution Shook America (Da Capo, 2006). He has worked for the Library of Congress since 1977, contributing to World War II: A Library of Congress Desk Reference (Simon & Schuster, 2007) and The Civil War: A Library of Congress Desk Reference (Simon & Schuster, 2002). He writes a weekly column for the Advocate newspaper. His blog, blogbort, can be found at www.hartfordadvocate.com.

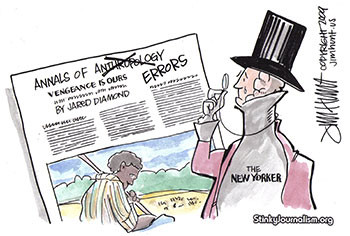

Jim Hunt is a cartoonist who published his first cartoon way back in 1989. It was an editorial cartoon for The Charlotte Post. Almost twenty years later, he is still doing cartoons for them. Though he attended the Mass. College of Art in Boston, he really learned how to draw cartoons where everyone else did… On his notebooks in school! Hunt lives in Annapolis, MD, with his wife and two daughters. Go to Hunt’s online portfolio .