(Credit: Pixabay)

A new CNN/Des Moines Register/Mediacom poll, conducted among likely voters in next year’s Iowa Democratic Caucuses, finds Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders losing support, while Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg gain support. Among the other four of the top eight candidates, there is little change.

A similar Iowa poll was conducted by the same polling consortium in March. In both polls, respondents were asked not only their top choice, but their second choice as well.

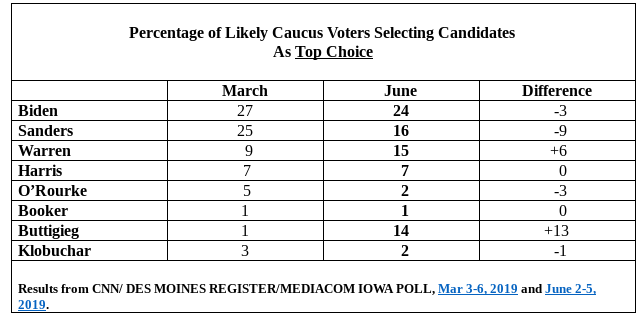

The table below shows how candidates rank as the top choice among voters in March and June:

Note that Biden slips just three points, remaining in first place. Sanders drop nine points, while both Warren and Buttigieg gain enough support to essentially tie with Sanders. Harris is in fifth position, with no change in support from March to June.

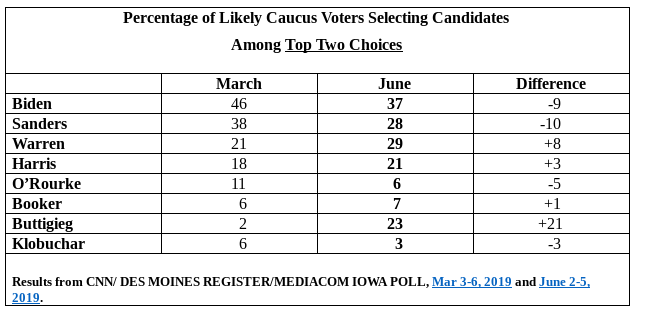

Given the number of candidates, an examination of voters’ top two choices provides, perhaps, a more insightful picture of potential candidate support.

As shown in the table below, compared with the Top Choice results, the Top Two Choice results reveal a somewhat larger drop in support for Biden, showing that he has lost support both as voters’ first choice and second choice.

Harris has considerable second choice support, putting her clearly in the top five ranks, essentially tied with Buttigieg.

The net result is that as of today, just five candidates have top-two support greater than 20 points in Iowa, while the other three candidates among the top eight, have only single digit support.

Six Points to Consider

1. The national primary polls are misleading

According to RealClearPolitics, national polls on average show Biden with a 17-point lead over Sanders, who has a 9-point lead over Warren, who is essentially tied with Harris and Buttigieg. In Iowa, however, Biden’s lead is only about half his national lead, and Sanders, Warren, Buttigieg and perhaps Harris all seem to enjoy about the same level of support.

There is no national primary. Projecting national results onto state primaries is backwards. Once the primary season begins, the national figures will fluctuate based on what happened in the states.

In the meantime, during this early period of the campaign, the national results reflect mostly name recognition. If we want to get an idea of how the primary will play out, we need to follow polls at least in the first four states that will vote: Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina.

2. Voters can change their minds quickly, especially in primaries

The poll showed that voters were twice as likely to say they will vote for a candidate who is electable than one who represents their own policy positions. The perception of who is most electable can change dramatically, depending on the latest news.

Even voters who say they will vote for a candidate with their policy views can very easily change their preference from one candidate to another – because in party primaries, many of the candidates have very similar policy positions.

We should not expect stability in voter preferences.

3. Polls are increasingly unreliable because of low response rates

Response rates in the past several elections have plummeted. Today, they are so low, we can’t really count on polls to get representative samples of the electorate.

According to Ann Selzer, the pollster who conducted the poll, interviewers called 3,766 telephone numbers of registered Democratic voters in the state, and ended up talking with just 652 voters (600 of whom indicated they were likely to vote in the Caucuses). That means just 17% of the voters who were called actually participated in the poll, while 83% did not.

It’s impossible to tell how different the 83% group is from the 17% group, but we can’t be sure that the smaller group is actually representative of voters overall. We shouldn’t be surprised if the poll results vary significantly from the actual electorate.

4. What happens in Iowa…may or may not be crucial to several candidates

As a general rule, results in the Iowa Caucuses have not accurately predicted a party’s eventual nominee among non-incumbent candidates. Sometimes they have, more often they have not. George H. W. Bush (1980), Bob Dole (1988), Mike Huckabee (2008), and Ted Cruz (2016) are among Republicans who won Iowa and fared poorly after that.

Among Democrats, the Iowa winners have generally gone on to become their party’s nominee, with two exceptions: Tom Harkins in 1992 (he was from Iowa, so the other candidates didn’t compete), and Richard Gephardt in 1988.

Whatever the eventual success of the Iowa winners, the Caucuses have generally helped to narrow the field of candidates. In this election cycle, with more than 20 Democratic candidates, the results are virtually certain to have a major winnowing effect.

Still, with so many contests quickly following Iowa, in states with large minority populations compared to Iowa (such states as Nevada, South Carolina, and California), the effect of the Iowa results on the higher tier candidates could be smaller than it has been in recent years.

5. Eight months until the Caucuses is a long time

There’s a lot that can happen in the next several months to upend expectations about the candidates who might dominate the campaign. Between now and February, there will be seven debates among candidates who qualify – at the end of June, the end of July, the middle of August, and one per month thereafter.

In addition, the volatility of the current political environment is bound to affect candidate standings – including such issues as potential impeachment of the president, Supreme Court decisions on congressional subpoenas, potential war with Iran, and the state of the economy.

These events are likely to magnify the potential volatility of the primary electorate.

6. All that said, the results may provide some early indications of candidate strengths

Personally, I’m inclined to sit back and wait until patterns are clearer. I’ve made too many bad predictions over the years to have much confidence in poll numbers this far ahead of the election.

For a less cowardly point of view, you could look at James Downie’s article in the Washington Post, where he argues “The latest Iowa poll means more than you think.”

Maybe he’s right. And maybe not.