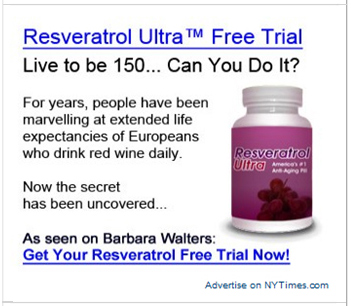

Does anyone ever live to be 150? An ad that appeared on nytimes.com for "Resveratrol Ultra" directly next to "With Resveratrol Buyer Beware" article suggests popping these magic pills could grant "150" years of life and touts Barbara Walters as endorser.

A New York Times Science section article decries fake turn-back-the-clock dietary pill ads misrepresenting famous personalities and deceiving online readership even though the newspaper’s own Web site features these fraudulent ads—one even challenges readers to “Live to be 150 years.” The Times admitted wrongdoing by falling asleep at the wheel while these suspect ads ran next to its very article condemning them and said the paper is “currently investigating ways to ensure this does not happen in the future.”

|

With Times’ “Resveratrol” Story, READER Beware! |

* * * * * * * * * *

An article “With Resveratrol, Buyer Beware” published in the Science section of the New York Times on Aug. 18 takes aim at various Web advertisers—specifically age-reversing drug supplement companies—hawking their wares using deceptive cyber practices. However, omitted from the story is that The New York Times itself is at best nonchalant in its ad screening practices, and at worst complicit in trafficking these same deceptive Web sites–not disclosing the conflict they are lining their own pockets with ad revenue from this scam.

Times Takes A Cut From A Click

As part of an exclusive series, iMediaEthics has investigated egregious maneuvers by various magic tablet and mythical fruit purveyors including: dummy Web sites, faux news stories and outlets, fake journalists and bloggers with false claims that spit in the face of the Federal Trade Commission. (Last week, we revealed that Rachael Ray obtained lawyers to fight the rip-off of her name and image for bogus diet ads on MSNBC).

Our investigation continues its focus on the role media outlets play in perpetuating such consumer frauds. The New York Times, in its Aug. 18 article, fails to even mention this aspect. The article portrays the big biz broadcasters ABC and CBS as victims (falling prey to fraudulent advertising) because their logos have become fixtures on dietary supplement pusher sites. Yet, many content providers and the New York Times, in particular here, are just as guilty for raking in profits from these ads while continuing the pretense of their journalistic objectivity.

The Aug. 18 article, “With Resveratrol, Buyer Beware,” anchored at the bottom of page D4 of the Science section. In it, reporter Sarah Arnquist focuses on the advertising blitz by seemingly endless volume of fad dietary supplement companies that push resveratrol. Made from a compound found in red wine grapes, resveratrol is sold in pill form and is claimed to put the brakes on aging.

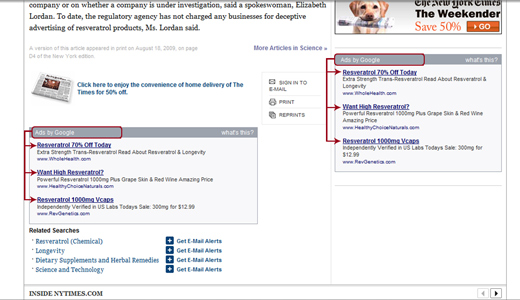

In addition to the ads usurping offtrack readers vulnerably clicking on these ads by accident or intent, the prima facie claims deserve a laugh meter. The pitches are tempting: “Live to be 150 years… Can You Do It?” for Resveratrol Ultra or “Improve Eyesight” offered if you take RevGenetics.

The “…Buyer Beware” article on nytimes.com is riddled with ads below and on the side of the story; all pitch resveratrol dietary supplements deals. Two sponsored link ads are easily seen as misleading and against FTC guidelines—The one ad web site, Healthy Choice Naturals promises that you will “Live Longer.” Another by Wholehealth.com promises “specifically, up to a 40% increase in life span!”

Online, when navigating to Arnquist’s article on the New York Times Web site, we found three to six “Sponsored links” in Google ads boxes. Many have questionable claims –easily found– in their pitch. iMediaEthics contacted three of the dubious advertisers, but only one responded. Anthony Loera from RevGenetics with its attempts to “avoid the bait-and-switch” with the $12.99/bottle price tag offered up front, boasts a clientele that he says mainly consists of professors, lawyers, doctor’s, and researchers. He explained through e-mail that his ads float around in a sort of manifest destiny fashion while streaming through Google and “sometimes we show up where Google provides the ads, such as The NY Times.”

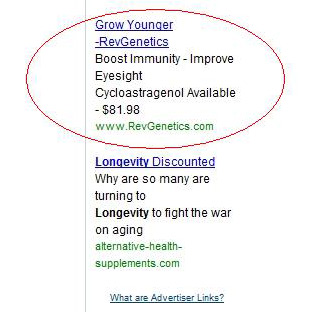

One RevGenetics ad that we found on a jump page after a search on nytimes.com suggests that buying pills will allow folks to shed their eyeglasses and ditch refilling contact lens prescriptions. With the tagline: “Grow Younger…Boost Immunity – Improve Eyeseight” there’s clearly false promises being set.

For his part, Loera professes to be an advocate against promoting immortality. Many potential customers–some with irrational expectations who probably are looking to skip the gastric bypass or plastic surgeries by digesting his dietary supplement are dissuaded at the door. Loera explained, “I have talked to folks on the phone asking about weight loss, looking younger, and some other silly things from a product that hasn’t been proven to do things in humans. On the phone, I have told folks that if they are buying our products specifically for weight loss, then they are buying the product for the wrong reasons.” On the homepage of his site is a rare warning that denies any affiliation with celebrities Dr. Oz and Oprah.

Asked about “Improve Eyesight” results from using his product Leora distinguished the ad wording taken from “interesting facts” and it shouldn’t be confused with “claims” from the product itself. He said that once landed on his Web site viewers can read a disclaimer that discerns between scientific results and the performance of his product. That disclaimer reads:

“The following mentions research done in animals and/or in labs. We do not claim our products will act in a similar fashion in regular people. As a dietary supplement company, we only present the information for your consideration and make sure we provide a great natural supplement.”

After we questioned his ad’s aims found on nytimes.com Leora said he will take actions to reword it. “Our marketer may have taken this a step over what I would have. So I will ask him to edit it and make it easier for folks to consider, while we review what message he was going for, when it was originally posted.”

Take pills and give up eyeglasses? A far-fetched fact in an ad for RevGenetics appears on the right column next to search results listed on nytimes.com.

Time To Take Times To Task

Asked why ads pitching resveratrol were placed next to an article decrying unsavory online practices, the Times’ reporter Sarah Arnquist blamed Google’s algorithm and directed us to her editor Laura Chang.

In an e-mail to Ms. Chang, we included several screen grabs and the original e-mail correspondence between Arnquist and her source Bill Sardi. Almost two weeks before publication of Arnquist’s article, Sardi was alerting the reporter through e-mails to a major slip-up, in which several fraudulent ads were placed next to another investigative article, this one in the Los Angeles Times. In one particular exchange Sardi wrote Arnquist about a Los Angeles Times article on the same topic published a month before hers, adding large red arrows that virtually shouted “Don’t Repeat This!” His efforts must have fallen on deaf ears–err, blind eyes.

In response to our inquiries, New York Times’ editor Laura Chang e-mailed a church and state defense: “Writers for the News Department of The Times have no control over what advertisements run in the newspaper or on the Website. Your criticism is therefore misdirected. But it raises questions which editors will need to take up with the advertising department. Thank you for bringing the matter to our attention.”

Subsequent questions were posed to Chang and to Public Editor Clark Hoyt’s inbox. Soon these queries were front-lined to Director, Public Relations at The New York Times Abbe Serphos who offered some insight into how The Times relies middlemen to green-light their online advertisements.

When In Doubt, Blame The Messenger

It’s easy to pin the blame on Google or Ad Networks. They certainly have to explain how their countermeasures for screening-out such tainting ads failed in these instances. But third parties aside, our research found a display banner ad on The New York Times Web site—right next to Arnquist’s “Buyer Beware” article—preaching that you will “Live 150 Years”.

Close-up look at an ad appearing on nytimes.com from Resveratrol Ultra with lavish claims for longer life and falsely suggesting Barbara Walters’s endorsement .

The above advertisement has no ties to Google whatsoever. And such boasts about longevity are in direct breach of FTC guidelines that clearly state that the media provider should snuff out such fictitious claims. “…Furthermore, the law requires companies to have adequate support for the claims made in the ad before the ad is run, so legitimate advertisers won’t be surprised by your request to see some backup information.” Could the New York Times lend any scientific support to an ad claiming you could live past 150 years? 110 years, even?

According to the article, numerous companies are hijacking star powerhouses such as: Barbara Walters, Oprah Winfrey and her scrub-suited sidekick Dr. Mehmet Oz. The accused companies snatch their likenesses or recorded TV segments giving the hosanna to the anti-aging findings and then plug these soundbites as endorsements to close sales to members of the celebrity’s fan base. Moreover, the names and corporate logos of CBS and ABC, for example, are also propped for display suggesting that they are prey to such deceptive business practices.

On Wednesday, Aug. 19, Oprah and Dr. Oz filed a lawsuit in Manhattan Federal Court to formally go after up to 50 false advertisers including many in the dietary supplement sector. The complaint reads: “Defendants are fabricating quotes or falsely purporting to speak in Dr. Oz’s and/or Ms. Winfrey’s voice about specific brands and products that neither of them has endorsed.”

While celebrities have a vested interest to save face, what’s more concerning (and so far has gone unreported) is that many media outlets are profiting off these fraudulent ads.

The Times’ Ms. Serphos in her email to iMediaEthics quickly cited a resveratrol ad that was barred from The Times in July 2009 “due to its unfound claims”. She states that the reason why this bogus “150 years” ad appeared alongside Arnquist’s article “came through an ad network targeted content in display in ways we do not allow.”

The Times advertisement buys either directly or with a third party, Ms. Serphos’s explains. Two third party vendors for TheTimes site are Ad Networks and Google. The resveratrol ad promising “150 years” of vitality carried an “Advertise on NYTimes.com” slug at the foot of the ad.

“That lets us know when an ad is sold directly or by a third party,” said Ms. Serphos. “The Resveratrol display ad carried that slug, as it came in from an Ad Network. It is not a New York Times display ad.”

Enter in Steph Jespersen whose title of Advertising Acceptability is to monitor material and stamp a ye or nay on online ads. Mr. Jespersen was away on vacation and thus did not respond to calls for comment. But Ms. Serphos did state that this issue is not taken lightly at the paper. She wrote, “We take matters of this nature very seriously and are currently investigating ways to ensure this does not happen in the future.”

Further, Ms Serphos said the paper plans a multi-pronged attack to address these issues and dialogue with their ad partners is in the works. “We will discuss with Google and their AdSense for Publishers team how we can prevent unacceptable products (like Resveratrol) from getting on the site via the text ad program.”

Again, finger pointing blame on the Ad Network, Ms. Serphos said the paper would do a more vigorous screening with “targeting technology” to prevent future embarrassing conflicts of interest. She noted,”…we will work with our Ad Network associates to determine which network violated our terms in multiple ways: by accepting ads from products we don’t allow (i.e. Resveratrol), but also by deploying targeting technology that resulted in the ad being positioned opposite highly relevant content.”

The paper would not, however, insert a retroactive financial conflict of interest disclosure to the Science Times article in question. Ms. Serphos wrote, “No, the article speaks for itself.” However, if the article “speaks for itself” without mention of The Times participation and garnering of financial benefit, then the blame game returns to center and the guilt lies squarely with these ad companies–NOT The Times or the other media providers profiting from green-lighting the bogus ads posted on their Web pages.

FTC Is Around For Good Reason

Bill Sardi is co-founder of Las Vegas-based Resveratrol Partners that produces a dietary supplement called Longevinex. According to Sardi, his company does business within the FTC provisions, unlike the ruthless competition who strategically base themselves offshore in places like Cyprus, China and Canada and ride on the coattails of venerable news reports from 60 Minutes to CNN.

Further, Sardi’s Longevinex and his verbal badge of honesty are elicited in the story–but links to his site are left out. Only two suspicious URLs are plotted in the article’s copy. Sardi feels shunned. “The NY Times gives you two links that are fraudulent sites,” he said. “Do you know what a link is worth in The New York Times? It’s worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Did they link to my legitimate site? No. They linked to my illegitimate competitors that are making all these fraudulent offers.”

He goes on to suggest that permitting these ads to be grouped next to the New York Times article about online fraud is for profit’s sake. “They’re [the New York Times] leading you to the very fraudsters they’re reporting about,” said Sardi. “Their complicity has become a crime syndicate.”

“They’re not writing for true journalistic value, they’re writing to get a click. They’re yelling about the fraud but they’re part of it.”

Go To The Source—Or Use Him For All He’s Worth

Resveratrol scientist and Harvard associate professor David Sinclair is one of the prominent researchers whose research results let the cat out of the bag. His findings led him to co-found a drug company that was bought out by pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline for $720 million over a year ago.

Despite being front and center in many online ads from a 60 Minutes item where he was featured, Dr. Sinclair told iMediaEthics last week through e-mails that he was adamant that he’s not affiliated or endorsing any company that sells consumer products. He expressed his reservations about any drug supplement company commandeering his name as an authority in the science to garner instant buys. He said in one e-mail response, “I have asked lawyers to see what we can do to stop the ads using my name and image.”

Interestingly enough, most media companies and news agencies, not just The Times, have on their payroll people who approve or veto various ads for their publications in print, video, or online. Ultimately they have to be awake at the switch to not run foul of FTC guidelines or to prevent other legal or internal policy violations.

Just a quick search through The Times sponsored link ads found offers up quick shots of hyperbole that renders prima facie, wrongdoing.

Two sponsored link ads next to the Times resveratrol story are easily seen as misleading and against FTC guidelines—The one ad web site, Healthy Choice Naturals promises that you will “Live Longer.” Another by Wholehealth.com promises “specifically, up to a 40% increase in life span!”

A Promise Is A Promise Is A Promise

It’s not enough to promise to look harder at ways to police the site. Merely accepting some fault is not enough in this case. “…Buyer Beware” was consciously speaking about fraudulent advertising and it’s clear that the writer Sarah Arnquist was warned well in advance that the possibility of her article could meet the same fate as The L.A. Times article, where the very bogus ads being discussed were evoked in Sponsored links, next to the article. Yet, she did not report this fact, nor did concerned higher-ups do anything until iMediaEthics reported this problem to them.

Since The NY Times also has Google-Sponsored links, the reporter should have notified editors about the danger and management should have been been concerned about the perception, if not the reality, that The Times is party to the unsavory scheme that it is reporting on and profiting from.

The initial knee jerk defense offered by the writer’s editor: “Writers for the News Department of The Times have no control over what advertisements run in the newspaper or on the Website” would hold if there was no warning offered by her source multiple times prior to publication about this troublesome forthcoming conflict of interest that needed (and still needs to be!) disclosed.

Arnquist’s article completely begs the point that the media outlets running these ads are in-control. The FTC Commission advises the media on how they are held accountable to reject and report fraudulent ads. Go to: Screening Advertisements: A Guide for The Media. Therefore, the buck stops with The Times. Why doesn’t the paper turn off these ads that are harming the public?

It may be that the paper will integrate screening mechanisms to better protect stories in the future from getting cast a guilty net by association. However, by refusing to be up front and honest about the Times‘ participation in publishing bogus advertising suggests that they are in cahoots, not unwitting victims, with the dubious and sometimes often out-right fraudulent companies.

A disclosure is a small, fair request. And so far it’s been denied. We will be waiting for paper of record to do the right thing and ultimately restrict these Internet ads–and adhere to FTC guidelines to protect the public from harm.

A quick check today of Arnquist’s article on The Times’ site shows they were able to almost immediately get results. All the offending ads have been removed by Google and Ad Networks…or have they?

There are no more resveratrol ads evidenced. However, Human Growth Hormone and other questionable ads have taken their place. A click on the ad brings up copy that says, “From its well documented anti-aging properties to its effect on athletic performance, it’s no wonder HGH has been extensively covered by NBC, Newsweek, Dateline, Oprah Winfrey, and the American Journal of Medicine.” Ah oh. iMediaEthics’ investigation continues.