(Credit: NYT, screenshot, highlight added)

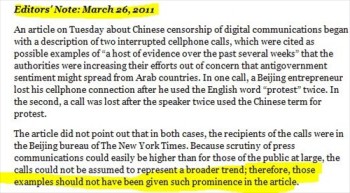

The New York Times has posted an editors’ note on its story about Chinese censorship. In part, the note read:

“The article did not point out that in both cases, the recipients of the calls were in the Beijing bureau of The New York Times. Because scrutiny of press communications could easily be higher than for those of the public at large, the calls could not be assumed to represent a broader trend; therefore, those examples should not have been given such prominence in the article.”

iMediaEthics wrote about American writer living in Shanghai Adam Minter’s fact checking of the Times’ anecdote that saying the word “protest” leads to dropped calls.

In a post following the Times’ editors’ note, Minter commented on the importance of the Times’ careful use of anecdotes:

“Insofar as the New York Times’ China correspondents hold the most important and influential foreign media jobs in China, their stories, standards, successes and failures, reflect on all foreign media in China. And, for better or worse, this ‘protest’ story does, too: from now on, it will be one more example for foreign media detractors to use as proof that ‘foreign media lie/make stuff up.'”

Minter also raised an interesting point, noting that Sharon LaFraniere, one of the Times reporters credited with the story, is married to Times Beijing bureau chief Michael Wines. Minter wondered:

“Could that relationship have played a role in getting this otherwise unverifiable anecdote into the paper? Only Wines can answer that. As for me, I can only assume that Wines’ relationship to LaFraniere complicates, if not affects, any actions that the NYT might want to take (against LaFraniere, in particular) in the wake of this incident.

“In the meantime, we are left with a question fit for a journalism ethics course: ‘You are the editor of a major newspaper. How do you handle a case of potential journalistic misconduct committed by a reporter working for a bureau chief who is also her husband? Discuss.'”