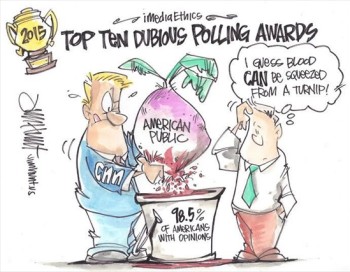

iMediaEthics cartoon (Credit: Jim Hunt for iMediaEthics)

Editor’s Note: iMediaEthics’ polling director David Moore collects the ten most dubious polls from the prior year in his annual Dubious Polling Awards. Below, read iMediaEthics’ top 10 dubious poll awards for 2015.

10. “Squeezing Blood Out Of A Turnip” Award

Winner: CNN for its uncanny ability to design polls that squeeze opinions out of (on average) 98.5 percent of Americans – including large numbers who are absolutely clueless about the issue being surveyed!

Credit: Wikipedia

Of course, CNN is not alone in squeezing opinions from the unengaged. Despite the fact that anywhere from a third to half the public really has no strong opinion on most issues, most media pollsters use forced choice questions (which provide no explicit “don’t know” response) and feed respondents information to create the illusion that around 90 to 95 percent of Americans actually know what’s going on in the world.

But CNN has taken this squeezing-blood-from-a-turnip mojo to a new level. In polling about the Islamic State (ISIS, or ISIL, or IS), for example, most of the pollsters reported anywhere from just under 10 percent to as much as 21 percent of their respondents volunteering that they were undecided about the issue. But CNN was able to squeeze the “undecided” down to less than 1.5 percent.

That’s not a trivial accomplishment. A Gallup poll in September showed just a third of Americans saying they were following the issue closely, with over a quarter having little to no familiarity at all with the issue. Yet, somehow, in the 28 questions it included in surveys in 2014, CNN was able to extract opinions from 98.5 percent of its respondents – ranging from a low of 97 percent to a high of 100 percent!

If only that fully engaged public actually existed….

9. “Remedial Math” Award

Winner: Fox News, which has shown, once again, that it doesn’t quite get the significance of 100 percent.

So, let us be clear (Fox News people, are you paying attention?): It means Everybody!

But at the beginning of last year, Fox presented a chart showing 137 percent of New Jersey residents had an opinion on whether Governor Chris Christie was aware of the infamous bridge closing. Which, as one can easily see, is a tad more than everybody.

This was not the first time that Fox News had shown a Rasmussen poll result with excess people. Fox also showed more people than is possible in 2009 when it presented a graph showing 120 percent of Americans with an opinion on whether scientists lied about global warming. (For that, Fox News won a coveted Top Ten Dubious Polling Award for “Fuzzy Math.”)

As Fox anchors will often admit (when suggesting climate change is not real), they’re “not scientists.” OK. They really don’t know what they’re talking about when it comes to global warming. But perhaps they ought at least to bone up on third grade arithmetic. What do you say, Mr. Ailes [CEO of Fox]? Time for a little remedial math?

Roger Ailes, Fox News’ president and CEO, in 2013. (Credit: Wikipedia)

8. “Precedent Trumps Reality” Award

Winner: Gallup for its annual December poll, showing that Vladimir Putin ties for sixth place as America’s “most admired” man.

Yes! That Vladimir Putin – the bare chested, horseback riding, homophobic dictator of Russia. Gallup says he’s America’s sixth most admired man in the whole wide world, tied with Bill Gates and Stephen Hawking, among others. Who wudda thought?

Vladimir Putin (Credit: Huffington Post)

This isn’t the first time Gallup has earned a Top Ten Dubious Polling Award for its faux “most admired” list – it was given the award for its 2009 list showing Glenn Beck the fourth most popular man in the world, more popular than Pope Benedict; and again when it found in 2010 that Beck was more popular than the Dalai Lama.

In 2010, Gallup’s Editor-in-Chief, Frank Newport admitted that Gallup’s “most admired” list didn’t really mean the people on the list were necessarily the most admired after all. It’s based on an open-ended question that really measures top-of-mind name recognition. However, he said, Gallup continued to ask the question in the same way year after year after year because it is based on “a historic Gallup precedent.”

There you go.

7. “Virginians Love Medicaid, Virginians Love Medicaid Not” Award

Winner: Christopher Newport University’s Wason Center for Public Policy, which conducted two polls on Medicaid expansion in the state of Virginia, producing completely contradictory views about the expansion of Medicaid.

(Credit: iMediaEthics illustration)

In the first poll last February, interviewers said good things about the expansion, and respondents said they favored it by a margin of 18 points, 56 percent to 38 percent. In the second poll two months later, interviewers said the money for expansion might not be available after all, and Republicans thought Medicaid had too much waste and abuse. With these warnings, the public now opposed expansion by a 12-point margin, 53 percent to 41 percent – a 30-point swing!

Was that a genuine shift in public opinion? Dr. Quentin Kidd, director of the Wason Center who conducted the poll says yes. But Geoff Garin, who polled for Virginian Governor Terry McAuliffe during the governor’s campaign, argues that the different results were “totally driven by the way the question is framed and the information [provided] in the question….”

Why was information provided to respondents anyway? Shouldn’t polls be measuring opinion rather than trying to create it?

6. “Blind Faith” Award

Winner: Cory Turner of NPR, who opined that two polls, with completely contradictory findings about the acceptability of the Core Curriculum, were nevertheless “both” right.

One poll, for the Harvard journal Education Next, reported a 27-point margin of support for the Core Curriculum. By contrast, a poll by Gallup/PDK came to the opposite conclusion – a 27-point margin against the Core Curriculum.

Turner asks the right questions:

“But can both polls be right? Can a majority of Americans oppose and support the Common Core?”

His answer:

“In a word: yes.

“Because, when it comes to polling, a word can make all the difference.”

OK, the pollsters did ask about the same topic using somewhat different question wording. Still, it’s important to note that they reported opposite conclusions. One might suspect that at least one of the conclusions was not spot on?

Still, given the state of the polling industry these days, it’s nice to know that the faith of some pollophiles can’t be shaken by mere data.

5. “March Madness” Award

Winner: NBC/Wall Street Journal Poll, Bloomberg Poll, Pew Poll, ABC/Washington Post Poll, CNN Poll, and HuffPollster/YouGov Poll.

No, this is not about college basketball, but about the series of conflicting polls about President Obama last March, conducted by our major media organizations – a period that can best be described as the madness of polls.

.JPG)

iMediaEthics photo illustration (Credit: Official White House photo, hand by Sarah Reid/Flickr, Flag by UP9/WIkimedia)

In early March, NBC/Wall Street Journal announced that Obama’s overall approval rating plunged to the lowest of his presidency, at the same time Bloomberg reported that his rating had surged to its highest level in nine months. Not only were the ratings different (41% approval by NBC/WSJ, 48% by Bloomberg), the trends were different as well – getting much worse, getting much better.

At roughly the same time, four other polling organizations had quite different findings about Obama’s handling of the crisis in the Ukraine: Pew reported public disapproval by a net 14 points; CNN net approval by five points; HuffPostPollster/YouGov net disapproval by five points; ABC/Washington Post an evenly divided public.

So many polls and so many different messages. One could go mad thinking they might be telling us something useful.

4. “Oops” Award

Winner: The polling industry for its less than stellar performance in the 2014 mid-term elections.

As HuffPollster noted the day after the election, while the polls alerted us to the possibility that the GOP would regain majority control of the Senate and increase their membership in the House, they nevertheless missed the margins of victory “by a mile.”

The polls’ performance in gubernatorial elections was not any better. At all levels, the polls systematically underestimated the Republican share of the vote, in several cases by double digits.

But, honestly, why should we as citizens care? After all, if the polls are wrong in what they tell us a day or two before the election, no problem. We’ll know what really happened in short order.

The problem for the polling industry, however, is that these election polls are supposed to demonstrate to all of us how accurate polls can be, because the election provides an objective standard against which to measure the poll results.

If election polls are accurate in predicting the winners, the theory goes, that should give us confidence in the public opinion polls at other times, when there are no objective standards by which we can validate what the pollsters tell us.

So, how did that work out for the pollsters this year?

Oops!

3. “The (Unauthorized) Stephen King” Award

Winner: The ABC/Washington Post poll for its scary coverage of opinion on the Ebola crisis.

(Credit: iMediaEthics illustration)

The media can scare the public. Or reassure it. When a medical crisis arrives, who knows which strategy is better?

The ABC/Washington Post pollsters, apparently, decided on the first strategy.

Their poll in mid-October reported “broad worries of an Ebola outbreak,” while a Gallup poll at the same time was more reassuring. It reported just 18 percent of Americans believing there could be a major outbreak, and only 14 percent who thought it “very” or “somewhat” likely they or someone in their family might catch the virus.

ABC also headlined that two-thirds of Americans felt the government should be doing more to deal with the virus, while Gallup again was more positive, reporting a large majority of Americans expressing confidence the federal government could effectively respond to the outbreak. Curiously, ABC/WP had a similar finding, but led with the scarier results.

And while the ABC/WP poll found a two-to-one majority saying the government was not doing all it could and should be doing more to deal with the problem, a Kaiser Family Foundation poll at about the same time reported a more sanguine finding – a plurality of Americans saying the government was doing enough.

Some of the differences among the polls were caused simply by question wording, since people really didn’t know much about the nature of the virus. Still, it was ABC and the Post that seemed most likely to emphasize how scared Americans were.

Was the public really that afraid? Ironically, only a week after the ABC/WP poll was published, Paul Waldman, a Washington Post reporter, commented on the “ample fear-mongering” that had taken place in the media and noted that “news coverage of the issue, so intense for so long, may be settling into a quieter, less sensationalistic period.”

Obviously, he wasn’t a Stephen King fan.

2. “(Sometimes) The Emperor Is Wearing No Clothes” Award

Winner: To Mark Blumenthal and Ariel Edwards-Levy of HuffPollster for acknowledging that public opinion polls don’t really measure public opinion when significant numbers of people are clueless about the issue.

OK…that sounds really insipid. Hardly deserving of a Top Ten Dubious Polling Award. Except that it’s rare when pollsters admit their polls don’t tell the truth.

Instead, pollsters and their followers generally pretend that the polls are always right (see the “Blind Faith” award) – that despite evidence to the contrary, the emperor is wearing plenty of clothes.

The polls in question this time include one by HuffPollster/YouGov, all of which asked how people viewed President Obama’s handling of the crisis in the Ukraine. The many contradictory results among the polls led to the “March Madness” Award noted earlier.

The question that Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy then ask is why the polls varied so greatly. In answer, they note that more than a third of their respondents admit they were following the issue “not very closely (21 percent) or not at all (15 percent).” The authors conclude:

“The large numbers [36 percent] paying just scant attention create the potential for inconsistent results across polls.”

Well, “inconsistent” is a bit of an understatement, given the widely conflicting results. But the point is that when much of the public is paying “scant attention,” poll results are hardly reliable. Many respondents are greatly influenced by the information embedded in the way different pollsters ask the questions, since such respondents have so little information themselves on which to base an opinion. Thus: Different questions, different responses.

But here’s the rub. The “scant attention” that Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy attribute to inconsistent poll results in this case is actually rampant! The two HuffPollsters leave the impression that it’s not the norm for large numbers of Americans to be ignorant about policy issues. But Pew polls suggest the opposite.

Pew’s format for measuring public attentiveness is the same as that used by Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy (how closely people follow an issue). So, take a look at this most recent Pew poll, which reports on how closely people have been following numerous issues.

Keep in mind that Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy suggest that when “scant attention” reaches “about a third” of Americans, the polls can’t be trusted.

The issues noted in the table were all well-covered in the news media at the time of the survey. Yet four of the five greatly exceed the “one-third” threshold showing “scant attention” by the public, and the fifth one comes very close.

But there’s more bad news. In the poll topline, Pew provides historical results for similar issues as the five noted above, providing a total of 131 measures. The average percentage of people paying “scant attention” to all the issues is just over 40 percent! The norm for those issues is actually higher than the threshold percentage noted by Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy.

How many times did the Pew polls show at least 36 percent of the public paying scant attention to an issue? The answer: 92 out of 131, or 70 percent.

Of course, the issues that Pew asked about don’t represent a perfect representative sample of all issues pollsters address. The public may be more informed about some other issues than these.

Still, the issues covered by Pew have been extensively polled, with pollsters claiming to have measured meaningful opinions. Yet, if we accept the analysis by Blumenthal and Edwards-Levy, 70 percent of those polls simply couldn’t be trusted.

OK. The good news is that polls don’t always suck. The emperor isn’t always naked.

Just most of the time.

Kudos to the HuffPollsters for at least admitting that the emperor is naked now and then. Now if they would just acknowledge the many other times as well.

1. “Polarize America” Award

Winner: Pew Research for flacking the idea of an increasing polarized America, even as its own polls provide evidence to the contrary.

Of course, as Washington gridlock makes clear, there is political polarization among the country’s congressional and political leaders. But among the general public, there is a much different dynamic.

One of Pew’s first reports in 2003, “Evenly Divided and Increasingly Polarized,”1 claiming that the public was also becoming more polarized and angry, was immediately refuted by Robert J. Samuelson.2 Later, his arguments were buttressed by Morris Fiorina and his colleagues in the book, Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America.3

But those arguments haven’t prevented Pew from pushing its polarization project again this past year. What Pew has shown, in fact, is a closer correlation between party identification and several policy positions and political values, especially self-professed ideology (liberal to conservative). That’s what the graphs show at the top of this segment.

However, polarization of a society is not measured by correlating attitudes among variables, but by determining if there are intense feelings on either side of issues. When there are many intense people on both sides of an issue, for example, with few people in the middle, then there is “polarization” – two poles far apart from each other. A graphical depiction would show a U-shaped distribution.

The problem for Pew is that it infrequently measures intensity on issues and values, so it’s generally not in a position to use such data to show polarization.

When Pew does measure intensity of attitudes, however, the results almost invariably contradict the notion that American attitudes fall into a U-shaped distribution.

In its 2014 Political Polarization and Typology Survey, for example, it found a more-or-less upside-down U-shaped distribution, with many more people in the middle than on either end of the spectrum – the reverse of a polarized distribution.

Note that a majority of Americans are in the middle in their evaluations of both parties. People with intense feelings are in the minority – 24 percent “very” unfavorable and 7 percent “very” favorable for Republicans, 23 percent and 12 percent respectively for Democrats. If Pew were right about polarization, there should be large numbers of people with “very” favorable and “very” unfavorable feelings about each party. But there aren’t.

Pew also shows no polarization on abortion – 19 percent want abortions legal in all cases, 14 percent want them to be illegal in all cases, while 59 percent want some restrictions – the middle position.

When asked in principle how much Obama and the Republicans should compromise, Pew again found results showing an inverted U-shaped distribution, with most Americans taking a middle position, saying each side should get about half (plus or minus 10 percent) of what they want. Few people took the extreme positions – that either Obama or the GOP should get virtually everything they wanted.

Like Pew, most polling organizations rarely measure intensity of opinion. But when they do (asking if people feel “strongly” or “not strongly” about an issue), the results almost always show many more people taking a middle position than taking an intensely pro or con position.

When the NBC/Wall Street Journal, for example, recently asked whether Americans approved or disapproved of creating a pathway for foreigners living illegally in the U.S., 23 percent strongly favored and 25 percent strongly opposed the idea, leaving a majority (51 percent) taking a middle position: somewhat favor, 34 percent; somewhat oppose, 14 percent; no opinion, 3 percent.

In May 2011, the NBC/Wall Street Journal poll asked about keeping troops in Afghanistan for the next three years, and included a measure of intensity. Again, a majority of Americans (57 percent) took a middle position, with 26 percent “strongly” disapproving and 17 percent “strongly” approving. The middle positions included “somewhat” approving (35 percent), “somewhat” disapproving (20 percent), and 2 percent no opinion.

To find more examples, one can peruse the many, many poll results reported in, among other places, the Polling Report. The polls that have actually measured intensity of opinion usually show that there are many more people in the middle than on either extreme of an issue.

That picture is consistent with polls showing that most Americans prefer the parties in Washington to compromise on issues, to find common solutions.

The bipolar America that Pew presents is at best misleading, a serious mis-diagnosis.

But, like Gallup with its “most admired” list, Pew appears to have too much invested in this distorted picture of an increasingly polarized America to recognize a more complex reality.

********************

1 “Evenly Divided and Increasingly Polarized,” Pew Center for the People & the Press, released November 5, 2003, 3:00 pm.

2 Robert J. Samuelson, “The Polarization Myth,” Washington Post National Weekly Edition, Dec. 8-14, 2003, p. 26.

3 Morris P. Fiorina, with Samuel J. Abrams and Jeremy C. Pope, Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America, Third Edition (Longman, 2011).

.JPG)