With President Obama’s recent visit to Cuba, there is renewed interest in how the American public views the efforts at rapprochement. A Gallup poll conducted twelve years ago, and a CBS poll just over a year ago, help to put current public opinion measures in perspective.

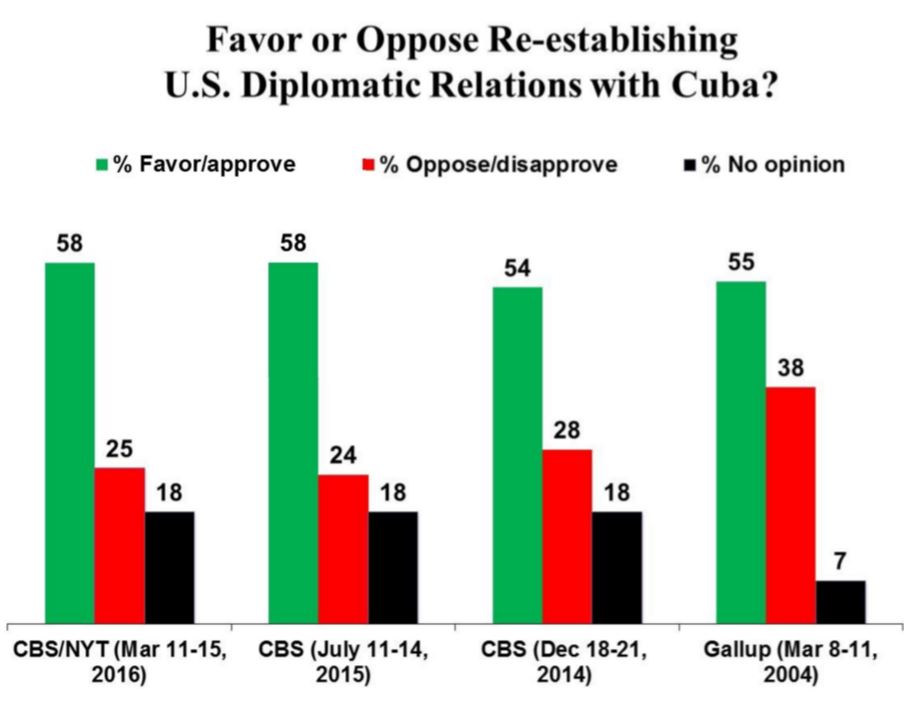

A CBS News/New York Times poll conducted in mid-March found widespread public support for re-establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba: 58% in favor, 25% opposed, and 18% with no opinion.

Previous polls by CBS and the Times produced similar results, as did a poll by Gallup back in 2004*:

Diplomatic relations were actually re-established last July 20, though the first announcement that the rapprochement would occur was made in December, 2014. The wording for all the questions was essentially the same: “Do you favor or oppose re-establishing U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba?” The only variation was in December, 2014, when CBS asked if respondents approved or disapproved, rather than favored or opposed. And the phrase included both “diplomatic and trade” relations.

Note the consistent level of support, from 54% to 58%. Gallup’s 2004 poll shows somewhat greater opposition and a smaller “don’t know” response than the other polls, perhaps because Gallup interviewers were more likely to press respondents for an answer.

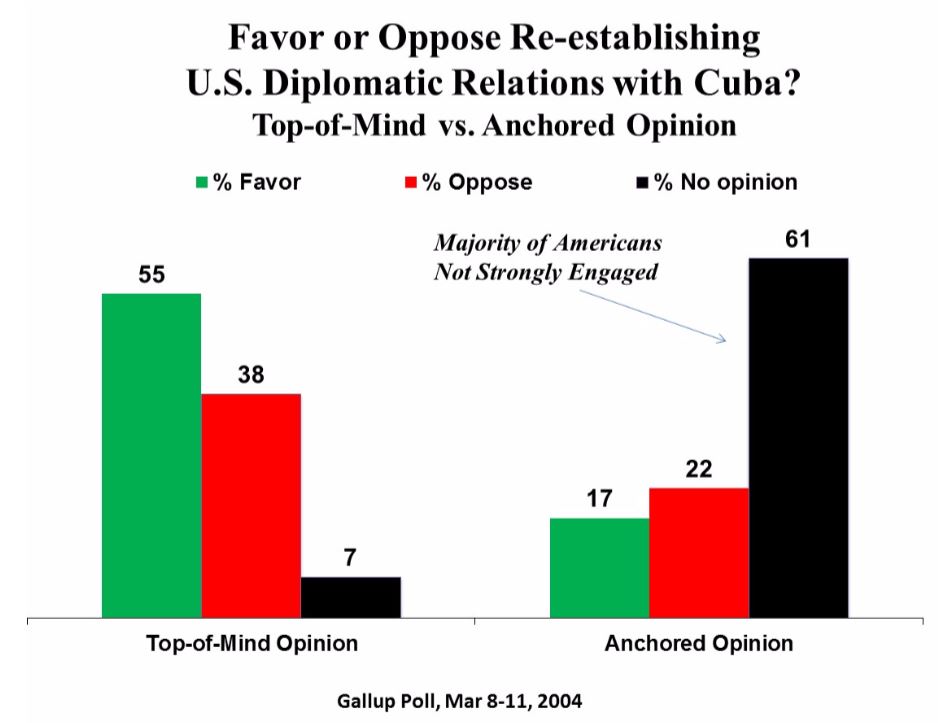

I include the Gallup poll from 2004 because that poll included an experiment, run by my Gallup colleague, Jeff Jones, and me, which was designed to test respondents’ commitment to their own opinion.

While the Gallup poll suggests that 93% of American adults have a meaningful opinion on the issue (only 7% unsure), and the three polls by CBS suggests that 82% of American adults have such an opinion (18% unsure), the experiment we ran suggests that these high numbers are highly misleading.

Anchored Opinion

The follow-up questions in the Gallup poll asked respondents who said they favored re-establishing U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba how upset they would be if the U.S. did not re-establish diplomatic relations. And respondents who expressed opposition to the idea were asked how upset they would be if diplomatic relations were re-established.

Respondents who said they would be “very” or “somewhat” upset if their opinion were to be ignored were classified as having a “meaningful” or “anchored” opinion. Respondents who said they would be “not too upset” or “not at all upset” were classified as not having an “anchored” opinion. Essentially, they wouldn’t be upset no matter what happened.

As these results make clear, the “top-of-mind” opinion, generated by asking a forced-choice question (no explicit “unsure” option offered) and not followed up with an intensity measure, produces the illusion of an almost fully engaged public.

Once respondents are asked whether they really care about their opinions – that is, whether they would be upset if their opinion did not prevail– it becomes clear that most people don’t really care one way or the other about the existence of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Cuba.

Although this Gallup poll is a dozen years old, the fact that opinion has been so consistent over the years suggests that the “anchored” opinion measured in 2004 is probably not much different from “anchored” opinion today.

As additional evidence, take a look at the CBS News poll in December 2014, when, uncharacteristically, the pollster asked two questions about the same issue – one which was a forced choice question and the other which offered an explicit “unsure” option:

Forced-Choice Question: “Do you approve or disapprove of re-establishing diplomatic and trade relations with Cuba?”

Question with Explicit “Unsure” Option: “Do you think the recent agreement between the U.S. and Cuba is good for the U.S., bad for the U.S., or don’t you know enough to say?” (emphasis added)

The questions do offer a nuanced difference, because theoretically one could disapprove of the action but still think it was good for the U.S., and vice versa. The key point here, though, is that the forced choice question pressured all but 18% of respondents to take a position on the issue. In the second question, where respondents were offered an explicit opportunity to indicate they didn’t have an opinion, 61% took it.

And that is similar to the 61% in Gallup’s 2004 poll of unengaged respondents, though the polls were conducted more than a decade apart.

As the Gallup poll makes clear, there has long been a widespread willingness of Americans to re-establish diplomatic relations with Cuba – the 17% in 2004 who strongly favored it, along with another 61% who wouldn’t have been “upset” if it had happened.

The poll also shows that there was widespread willingness not to follow that course of action – 22% who strongly opposed it, along with 61% who weren’t upset either way.

The truth is that on many issues, like this one, enough citizens are sufficiently unengaged, with no strong view one way or another, that it’s the political leaders who can decide to go one way or another.

And that’s what happened on this issue. That President Obama decided to act had little to do with public opinion, and more to do with his own judgment – just as the GOP leaders in Congress who oppose the action do so on the basis of their own judgment. Despite the polls, public opinion on this issue is at best an afterthought.

*Gallup Poll, March 11, 2004, with 1,005 adults nationally. MOE = ±3 percentage points. Timberline #: 140853; Princeton Job#:04-03-012