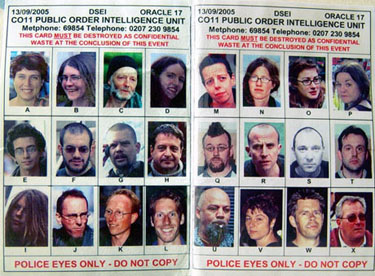

The Guardian included an image of a police spotter card in their original print report that was not connected to the online version of that story.

We recently wrote about the ethical issues that arise when blog posts are replaced with a different version or removed from websites altogether. When the content of a post exists only online, removing or correcting without providing the original content seems, at best, misleading.

But a situation at the Guardian is now raising questions about how a print publication should handle the ethics of maintaining, in perpetuity, print content online.

Last week the Guardian ran a 3-day series on the practice of UK police gathering intelligence information and monitoring individuals who participate in political meetings and protests. (The first story can be seen here.) As evidence, the Guardian included an image of a police spotter card, which writers Paul Lewis, Rob Evans, and Matthew Taylor, authors of the first story of the series, explain is “used to identify the faces of target individuals who police believe are at risk of becoming involved in domestic extremism.” The print edition of this story, which was published on Monday, October 26, included a spotter card — allegedly obtained when it was dropped at a demonstration — with the faces of 24 individuals.

Reader’s editor Siobhain Butterworth devotes this Monday’s column to the spotter card, setting out to address two ethical questions: “First, should the spotter card have been reproduced with the story? Second, assuming the use of the image met legal and ethical thresholds at the time of publication, should the unadulterated image remain on the Guardian‘s website indefinitely?”

But while her analysis and reporting seem to argue that the paper should, in this particular case, keep the card posted online, she doesn’t state outright the newspaper’s editorial decision. And because the link in her column leads to the front-page story, which doesn’t include the spotter card, and the related stories running alongside this front-page story don’t lead to the spotter card, it’s unclear that the newspaper did, in fact, decide to keep the card online. Even a link on the words “police spotter card” in a commentary piece by comedian Mark Thomas, who was pictured on the card, doesn’t lead to the image.

iMediaEthics spoke with Butterworth over the phone about her column. While it seemed that her article supported publishing the spotter card online, we were confused because it was difficult to find the original, unedited card. We found an edited version, with only the faces of the 11 individuals who were interviewed or wrote personal articles for the paper, here, but initially couldn’t locate the orignial, unedited card as it appeared in the print version of the story.

Butterworth refuted the idea that the column was in any way misleading. Although she recognized that the link in the first paragraph led to a story with a different image, she didn’t think that readers needed to see the spotter card to understand her column. “The purpose of the column is to explore an idea,” she explained. That idea is whether or not something that initially passes the threshold for publication should then live in perpetuity online.

While the statements in her column, from investigations editor David Leigh and reporters Rob Evans and Paul Lewis, support the idea of maintaining the spotter card image online, we pointed out that it’s confusing because the image is not easily visible . Her column (and stories linked to in her column) don’t lead a reader back to that spotter card. It takes a little digging — the card shows up on the third page of results in a search for “spotter card” on the paper’s website because newer stories about the spotter card have been written, pushing the original back in the queue.

Eventually, Butterworth remembered that she, in fact, had a difficult time finding the spotter card online when she began writing her column. When we pointed out that if she couldn’t find it, that perhaps readers would have the same problem, she said that she attributed her inability to locate the spotter card to an issue of “incompetence.” But if someone who works for the newspaper (who, we would hope, is familiar with their search engine) had a difficult time finding the spotter card, it’s not unreasonable to think that a reader might have the same problem.

Like at most larger news organizations, Butterworth doesn’t package her own stories. Links and related stories are added by someone else, in this case a sub-editor. Although Butterworth’s column strongly implies that the paper left the spotter card online, the way her column is packaged could provide more transparency about this decision, either with a statement from Butterworth making the editorial decision explicit (rather than implied), or through links and related stories.

Butterworth doesn’t believe that this is an issue of ethics. “I think your take on it is not itself ethical,” she said. While her column may not be intentionally unethical, the context in which it is published raises suspicions — especially considering that the newspaper received complaints from readers who felt that publishing the image was a breach of privacy. If the Guardian truly believes that they made ethical decisions in publishing the spotter card both in print and leaving it online, and the statements in Butterworth’s column certainly support that argument, then it should be made easily available to readers of Butterworth’s column and the original story with which it appeared.