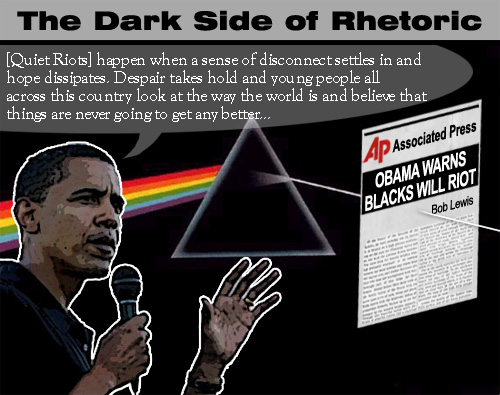

Barack Obama stirred up controversy in early June when he used the term “quiet riots” to describe an undercurrent of despair that only reveals itself after catastrophe, citing as examples the riots in Los Angeles in 1992 and the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. Reporting on the speech, AP writer Bob Lewis led into his story by writing that Obama issued a warning to the Bush administration that it has failed to defuse the threat of an imminent wave of riots in black communities. Lewis wrote what could surely be characterized as a sensational lede, but was it sensationalist?

Language is the basis of the political platform in the American electoral system. The distortion of political candidates’ speech for sensationalistic purposes engenders a very real threat of undermining the political process by misrepresenting the message of the candidate. But political language is of a special nature: rhetoric, which is language designed to persuade and is created with the expectation that it will be parsed and analyzed. Incidents, such as the “quiet riot” controversy beg the question: how does the journalist cover campaign rhetoric, balancing proper representation of the candidate’s speech, while determining the veracity of political language?

When Obama used the term “quiet riots” it was to describe a persistent condition of despair in ostensibly black communities. “They happen when a sense of disconnect settles in and hope dissipates,” said Obama. “Despair takes hold and young people all across this country look at the way the world is and believe that things are never going to get any better . . . That despair quietly simmers and makes it impossible to build strong communities and neighborhoods. And then one afternoon a jury says ‘Not guilty,’ – or a hurricane hits New Orleans – and that despair is revealed for the world to see.”

As an introduction, Bob Lewis wrote in his AP article, “[Obama] said… the Bush Administration has done nothing to defuse a “quiet riot” among blacks that threatens to erupt just as riots in Los Angeles did 15 years ago.” Lewis’ catchy lede was echoed by the national media, including by Paula Zahn on the June 6th broadcast of her eponymous CNN show. She introduced the controversy by saying, “[S]enator [Obama] said yesterday that there are quiet riots all over the country waiting to burst out in the opening [sic].”

But there is little in the way of the speech text that supports Lewis’ opening sentence. Sure, Obama made reference to the LA riots. But he also spoke of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, which, instead of riots, consisted of countless examples of government negligence in providing health and human services for that city’s beleaguered residents. Furthermore, nowhere in the speech did Obama explicitly blame the Bush administration for failing to address a coming eruption of violence.

Navigating the Shoals of Rhetoric

There is a great deal of variation among reporters in the coverage of political language. In order to figure out if there is an agreed upon standard, I called several journalism experts to get their take on just how much analysis, interpretation, and verbatim reporting should be allowed in political speech reporting. In fact, there are no formal standards; individual stories vary widely between straight reportage and extravagant sensationalism.

Roland Martin, a journalist and CNN contributor, wrote in an email exchange, “NOWHERE in the speech does Obama say the quiet riot ‘threatens’ to erupt.” Martin appeared as a guest on Paula Zahn’s broadcast and declared, “I actually read the speech. AP got it wrong.” Martin also placed blame on editors and warned that accuracy is a critical standard for journalists. “The copy editors read the lead and chose a headline suggesting that blacks are poised to riot based on Bush’s policies,” Martin wrote. “What we as journalists must do is be EXTREMELY careful as to what we write . . . We must get it right because when people see our work, they assume we are on the money. And even when we make a slight error or misread something, once that train leaves the station, it’s gone. And it’s hard to catch up.”

The political speech reporter is faced with a difficult task. Politicians often make vast and sweeping claims, work audiences with gimmickry, and employ tricky language to manipulate the messages of their opponents. Faced with such spin, the journalist must carefully unpack precisely crafted political speech. It is a tightrope act. Adhere stringently to the political message and the journalist becomes a stenographer; a de facto part of the campaign apparatus. Stray too far and the journalist interferes with the election process instead of illuminating the electorate. By publishing Lewis’ lead, the AP seems to have done the latter.

The 2004 election offers some examples of how acutely challenging reporting on strategic language can be. On September 8 of that year, John Kerry made the claim during a stump speech that “the cost of the President’s go-it-alone policy in Iraq is now $200 billion and counting.” But according to a September 13 article published on FactCheck.org, the Office of Management and Budget had actually put the total cost for the war, up to the end of that month, at $119 billion dollars. Kerry’s campaign had folded in other monies, including $60 billion the Bush Administration had not yet requested. For campaign journalists, reporting verbatim on this rhetoric would have been a dereliction of duty; this kind of quantitative statement demanded the type of fact-checking that FactCheck.org incorporated into its article.

On the other side of that contest, the incumbent president was no innocent of exaggerated rhetoric. According to a Washington Post article written by staff writer Howard Kurtz on October 13, 2004, a Bush campaign ad charged that Kerry’s healthcare proposal would cost $1.5 trillion dollars over ten years. But, as Kurtz noted, this calculation was made by the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute. Kerry’s own analysts, according to the article, had put the cost at about $635 billion. Kurtz reported that Bush also claimed Kerry’s plan was a government takeover, but in fact, the plan would have built upon an extant system of private health insurance. The sum total of both camps’ propensities to exaggerate was a task for journalists to sweep aside the rhetorical curtain and present to readers a reasonable assessment of the truth behind the politics. Repetition of the rhetoric, no matter how accurately, would have been a tacit allowance for campaign writers to determine the tone, language and veracity of the very campaigns they were invested in. Both Kurtz and FactCheck.org accurately reported on campaign rhetoric while at the same time providing analysis into the veracity of the claims.

Politics as Performance

Elizabeth Skewes, assistant professor at the University of Colorado at Boulder and author of “Message Control: How News is Made on the Presidential Campaign Trail,” was a member of the traveling press corps during the 2000 and 2004 presidential campaigns. In a telephone interview she notes the challenges for reporters who have to cover the same speech every day. “Reporters… are looking for that thing that isn’t scripted and that isn’t managed and that might show something more real about the candidate.”

A potent example of this kind of performance misstep was provided by John Kerry, who (unsuccessfully) joked in Fall 2006 that “if you make the most of [education], and you study hard and do your homework, and you make an effort to be smart, you can do well. If you don’t, you get stuck in Iraq.” The actual text of his speech, according to his website, was, “You end up getting us stuck in a war in Iraq. Just ask President Bush.” The joke was written as warning to those in the audience that poor grades could lead to catastrophe. However, the joke quickly turned into a blunder and cascaded through the media as an insult to American troops, effectively ending John Kerry’s budding prospect of running for the presidency again in 2008.

The zeal with which the mainstream media capitalizes on these unscripted moments may result in catchy ledes that inadvertently obfuscate the more nuanced points a candidate seeks to make. However, in this instance, Kerry’s words were reproduced faithfully, if not narrowly. Al Gore, on the other hand, was victim of the ambiguity of his own statements, which were easily manipulated by both the media and the opposing party during his 2000 run. Gore, being interviewed on March 9, 1999 by CNN’s Wolf Blitzer on “Late Edition” said, “I took the initiative in creating the Internet.” What many took from that comment was that Al Gore claimed to have invented the internet. While he probably intended no such thing, the media’s focus on that allowed political opposition to exploit the perception that Gore had a tendency to exaggerate.

Aly Colon who teaches ethical decision-making at the Poynter Institute said, in a telephone interview, a reporter must “try to think of the speech in context, which is to understand the candidate, why the speech is being made, why at that time, and what the candidate is trying to establish by making such a speech.” This involves “establishing themselves what they think the particular issues might be, what they believe they want the public to understand historically in context, as well as verifying with each candidate… what the candidate is trying to express.” Ultimately, Colon expresses the importance of “getting the facts right, and getting the context right…good political reporters try to do both.”

Wolf Blitzer, in March 9, 1999 Gore interview, would have done a better job if he had explored the context in which Gore was speaking, which was, in fact, his congressional record of “moving forward a whole range of initiatives that have proven to be important to our country’s economic growth and environmental protection, improvements in our educational system.” Instead, Blitzer shrugged off analysis and moved on to a hypothetical question about the polling numbers on George W. Bush and Elizabeth Dole.

Rhetoric, Redux

Let’s return for a moment to the idea of the rhetoric of political speeches. Bill Kovach, co-author of “The Elements of Journalism” and professor at the Missouri School of Journalism writes in an email, “It is important that a responsible reporter follow the candidate to many speeches before many audiences to … provide the audience with a sense of how consistently or inconsistently the candidate deals with the same issue.”

Guidelines for political speech reporting are even more stringently defined by Pulitzer Prize winner and former St. Petersburg Times Tallahassee Bureau Chief Lucy Morgan. In a Poynter.org piece, Morgan sets forth a series of journalistic “steps” including: covering the newsworthy content of the speech, checking the facts, gauging audience response, and reviewing the gimmickry of presentation, such as having an audience member present who exemplifies a subject covered in the speech. But Morgan also allows for latitude in the process. Morgan enumerated some of the day-to-day difficulties of speech reporting. “I don’t know of any formal guidelines for writing about speeches,” she wrote. “Most of us do it on the fly in limited time periods to make deadlines and we are often covering a politician who makes the same speech day after day, varying it only slightly so it is often difficult to find the news value.” Morgan, like Kovach, points out that context and verification are essential. “I wouldn’t limit the speech reporter to only reciting what he heard,” she wrote. “When a candidate makes an obvious misstatement that can be easily proved up, the reporter has an obligation to include that info in the story. I think we have an obligation to give [the speech] context and, where possible, determine accuracy.”

Accuracy v. Truth

Skewes of the University of Colorado, in her telephone interview, provides an underlying reason why speech reporting can be so problematic; it is a distinction between accuracy and truth. “The journalist is trying to get at what truth is – what’s the truth in this situation? – …realizing that the campaign’s truth is a shaded one.” Skewes makes the quintessential distinction that underlies the political journalist’s greatest challenge. On the relationship between accuracy and truth, she says “is that an accurate truth or does the journalist need to add in… other information that gets closer to what he or she feels that voters and the public need to know and have a right to know.” Accuracy and truth, she says, “don’t mean the same thing. Not necessarily.”

When asked about the distinction between accuracy and truth, Skewes explained the relationship between journalists and campaigns during day to day coverage. “Tension between campaigns and journalists comes from the campaign sense that they ought to control the message that gets to the public via the media…. Journalists say, the message that you want to send, because it is so carefully scripted, because it is so measured, needs something more, needs clarification.”

The image of the reporter that finally emerges from these various observations is one who must report on the scene of the speech, the context of the information presented, and the overlap between political rhetoric and political reality.

Where’s the Fire?

Returning to Obama’s June 5 speech, it becomes clear that Lewis’ lede extended beyond a reasonable analysis one would expect from political coverage. It is difficult to discern from the speech text where exactly Obama places blame on the Bush administration for failing to defuse the supposedly imminent black riots. He does place responsibility for obvious failings on the administration, as in the disaster after Hurricane Katrina, and he surely describes a feeling of despair and hopelessness in black communities across the nation. But in a close examination of the text, there is no direct reference to the Bush administration ignoring the warning signs of uprising. Nor can the phrase “quiet riot” be explicitly taken as meaning violence. Surely in New Orleans the predominant violence was the violence of government neglect for a city in peril. Lewis’ lead was flashy and spoke to a controversy cooked up through dubious extrapolation.

The result was a brief increase in media exposure for the Obama campaign. But instead of accurately representing a speech intended to address racial and social inequities, the coverage cherry-picked a “controversial statement.” Unlike Kerry’s gaffes, Bush’s misstatements, and Gore’s ambiguity, Obama’s statements were fairly direct and were reasonably explained in the text of his speech. The real controversy here is not in the speech, but in the singular interpretation of that speech by a lone reporter whose own rhetoric was spread far and wide across the news landscape.

Perhaps the best way to counter such hyperbole and inaccuracy is for editors and writers to be vigilant about their technique in political reportage and to provide as much substantiating evidence as possible. In an email exchange, Columbia School of Journalism professor Samuel Freedman says it best; “Ideally, in this era of online journalism, a news organization not only can report on a speech but can link to text, audio or video of the entire speech.” (Below is an example of how this might be done with the relevant AP article and Obama’s speech, with links to each.)

**At the time of writing, neither the AP nor the Barack Obama presidential campaign responded to requests for comment.

Reference:

https://www.imediaethics.org/obama/Remarks-of-Senator-Barack-Obama.pdf

https://www.imediaethics.org/obama/Obama-Warns-Quiet-Riot-Among-Blacks.pdf