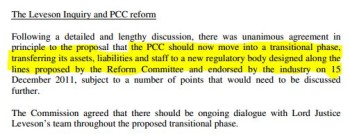

A screenshot from the PCC's February meeting minutes. (Credit; PCC ,screenshot)

The Press Complaints Commission announced it is closing to “offer the press a clean break from the past,” according to the Associated Press and the Guardian. The PCC has existed for 21 years, the Guardian noted.

According to the AP, last month the PCC “agreed in principle to abolish itself at a meeting.” According to the Independent’s March 7 article, “Details of the formal close-down date and the potential names of the new body are expected to be revealed in six weeks when the full minutes of today’s meeting are approved and published shortly afterwards.”

The PCC will be replaced with a currently unnamed transition organization until a “long-term replacement” can be established. According to the Guardian, “the long-term replacement for the PCC is not expected to be up and running for at least a year and may not be in place until 2014.”

We asked the PCC’s Catherine Speller for more information about this closure. She told iMediaEthics by e-mail that the PCC is “transferring its assets, liabilities and staff” to the transition body. She directed us to the PCC’s February meeting minutes (see here) which say:

“Following a detailed and lengthy discussion, there was unanimous agreement in principle to the proposal that the PCC should now move into a transitional phase, transferring its assets, liabilities and staff to a new regulatory body designed along the lines proposed by the Reform Committee and endorsed by the industry on 15 December 2011, subject to a number of points that would need to be discussed further.

“The Commission agreed that there should be ongoing dialogue with Lord Justice Leveson’s team throughout the proposed transitional phase.'”

We also asked Speller what will happen to unresolved complaints in the PCC’s system during this time period. She told iMediaEthics by e-mail that : “Complaints will continue to be considered in the usual way during the transition period. Clearly there are further discussions to be had but the main thing is that the decision has been made in principle to move to a transitional phase.”

The transition organization will “be run by three people “Michael McManus, a former Conservative special adviser, who is director of transition, with Jonathan Collett, the director of communications, who has previously acted as press adviser to former Conservative leader Michael Howard, and Charlotte Dewar, the head of complaints who previously worked at the Guardian,” according to the Guardian.

The National Union of Journalists issued a March 8 statement about the “closure announcement” saying that the group is “pleased” with the news. The NUJ added that it doesn’t want a “rebranding” of the PCC but a “new body” that will “ensure the freedom of the press” and “encourage good practice.”

The group said in part:

“Self-regulation has been given every possible chance to work in many different forms over the past 40 years and has failed the test every time. It is for this reason that for the past two years it has been the NUJ’s policy position – as set down by its democratic delegate meeting which forges and evolves policy on behalf of the 38,000 journalists in the union – that the PCC has shown itself to be incapable of genuine reform and that it must be dismantled and a new organisation created that cuts all links with the way business has been done in the past.”

See the NUJ statement in full here.

There has been much debate over the future of the PCC in the past year as phone hacking allegations continued against the now-closed UK News of the World.

In July 2011, the PCC’s chairperson, Baroness Peta Buscombe announced her resignation from the PCC. She was replaced in October by Lord David Hunt.In February, the PCC announced that its director of the previous two years, Stephen Abell, was resigning from the PCC for another job.

We wrote in December when the PCC called for suggestions from the public for revisions to its editors’ code of practice. In January, the new PCC chairman Lord Hunt proposed a “totally new” UK press regulation system at the Leveson Inquiry into press standards and practices. Hunt called for “real powers to investigate allegations” of press wrongdoing and the power to fine offending media outlets, among other suggestions.